|

|

|

|

|

KOREAN KANHWA SŎN BUDDHISM -- SPECIAL REPORT

|

|

Top Menu

Introduction

|

Architecture

25 Photos

|

Creatures

42 Photos

|

Deities

59 Photos

|

Doors

13 Photos

|

Paintings

64 Photos

|

People

32 Photos

|

Votive Icons

21 Photos

|

|

Korean Influence on Early Japanese Buddhism. Not a systematic study, but rather a "sketch" of the key contributions of Korean monks, artisans, and specialists to early Japanese Buddhist doctrine, art, and architecture. 30 Photos. Korean Influence on Early Japanese Buddhism. Not a systematic study, but rather a "sketch" of the key contributions of Korean monks, artisans, and specialists to early Japanese Buddhist doctrine, art, and architecture. 30 Photos.

|

|

KOREAN INFLUENCE ON EARLY JAPANESE BUDDHISM. Japan first learned of Buddhism from Korea in the mid-sixth century when the king of Korea sent the Japanese court a small gilt bronze Buddha statue and other Buddhist items. Buddhism's introduction to Japan was accompanied thereafter by the arrival of countless artisans, priests, and scholars from Korea. Additionally, large numbers of Koreans fled to Japan in the 6th and 7th centuries to escape incessant warring among the three Korean kingdoms of Silla (J = Shiragi 新羅), Baekje (J = Kudara 百済) and Koguryo / Goguryeo (J = Kōkuri 高句麗). These immigrants brought numerous Buddhist images and texts, and played major roles as Buddhist academics, teachers, sculptors, artisans, and architects. Many of Japan's earliest temple structures, for example, were made by Korean craftsmen (see below). Nonetheless, by the early 8th century, the Korean artistic influence began to wan and was eventually overshadowed by Japan's growing fascination with China and Chinese Tang-era culture.

|

|

|

Korea Introduces Buddhism to Japan -- First Buddha Statues in Japan

|

Buddhism was introduced to Japan in 552 CE (other sources say 538) when King Seimei 聖明王 of Korea sent the Japanese Yamato 大和 court (then based in the Asuka district near Nara) a small Buddha statue, some Buddhist scriptures, and a message praising Buddhism. The Nihon Shoki 日本書紀, one of Japan's oldest extant documents (dated 720 CE), says the statue was presented during the reign of Emperor Kinmei 欽明 (r. 539 to 571) and came from the king of a Korean kingdom called Kudara 百済 (aka Baekje, Paekche, Paekje, Paikche). Legend contents that the bronze statue was entrusted to the leader of the Soga 蘇我 clan, who acted as the chancellor of the young Japanese nation. But soon thereafter an outbreak of smallpox occurred, and clans opposed to Soga influence and Buddhism's introduction claimed the statue was responsible for the sickness afflicting Japan. The emperor, hoping to diffuse the situation, ordered the statue thrown into the Naniwa River, near the court's palace (now current-day Osaka City). The statue was thereupon pitched into the river. The discarded statue, it is said, was later fished out of the river following the victory (temporary) of the Soga clan, and is currently installed at Asuka Dera (Nara). This legend is incorrect, for the extant statue installed at Asuka Dera (see photo at right), cast in +609, is much too large to be the legendary "first" Buddha statue to arrive in Japan. Perhaps the extant statue is a giant copy of that first small Buddha statue? This latter issue has never been resolved. Conversely, others argue that the first Buddha statue to arrive in Japan is today found at Zenkōji Temple 善光寺 in Nagano Prefecture, which houses an image known as the Amida Triad 善光寺の阿弥陀三尊 (see photo at right). The triad was reportedly made in India, then traveled to China, and was brought to Japan by Hata no Kosedayuu 秦巨勢大夫 in 552 CE. In 664 the triad became a secret image (hibutsu 秘仏, i.e., not shown to the public). However, once every six years, a Maedachi Honzon 前立本尊 (duplicate or "stand in" image) is displayed to the public. See Zenkōji Temple for details.

Writes scholar Hank Glassman (page 1): "The history of Buddhism in Japan is from its very origins a history of images. The poles of attraction and anxiety marking the first encounter with the foreign religion and its icons set up an oscillation felt down through the centuries. It was the gift of a Buddha statue in the mid-sixth century from the Korean kingdom of Paekche (known in Japan as Kudara) that first inspired the court to embrace and propagate Buddhism. In the chronicler's account of this event, appearing nearly two centuries latter in the Nihon Shoki 日本書紀, the awestruck emperor and his court are drawn to the image's 'countenance....of severe dignity' and find the neighboring ruler's description of the power and truth of the Buddhist faith appealing, but they are not sure what course of action to take. There is considerable trepidation that bowing down to this god of foreign provenance might anger the local deities. From this time forward, the competition and cooperation between indigenous gods and imported ones was to be mediated through the visual field.

King Seimei 聖明王 of the Korean kingdom of Kudara dispatched Kishi Nurishichikei 姫氏怒唎斯致契 and other retainers to Japan. They offered as tribute a gilt bronze statue of Śākyamuni Buddha, ritual banners and canopies, and several volumes of sūtras and commentaries....Thereupon, the emperor inquired of his assembled officials, 'The Buddha presented to us from the country to our west has a face of extreme solemnity. We have never known such a thing before. Should we worship it or not?'" (FN 2, page 197, translation by William E. Deal).

Here we see the ways in which the face of the saint serves to foster a direct and visceral emotional connection." <end Glassman quote, page 1>

LEARN MORE: Early Japanese Buddhism (A-to-Z Photo Dictionary)

|

|

|

Korean Influence on Japan's Prince Shōtoku

|

Prince Shōtoku Taishi (574-622 CE), Japan's first great patron of Buddhism, lived at a time when Korean influence was perhaps near its peak in Japan. Immigration from both Korea and China can be traced back to at least the mid-third century. By Shōtoku's time, many of Japan's highest ranking monks and artisans hailed from Korea. These immigrants from Korea played instrumental roles in transmitting the Buddhist teachings and art techniques to the Japanese court, its court-sponsored art workshops, and the newly established temples that served as Japan's main centers of Buddhist study. The Koreans themselves had received the Buddhist tradition via China, and had adopted many of China's techniques for carving in wood, for making gilt bronze statues, and for reproducing Buddhist icons in vast number. See Making Buddha Statues for many more details.

Prince Shōtoku learned about Buddhism, it is said, mainly from two Korean monks. One hailed from the Korean Kingdom of Koguryo 高句麗 (Goguryeo), and was named Eji 慧慈. The other hailed from the Korean Kingdom of Kudara 百済 (Paekche), and was named Esō 慧聡. Prince Shōtoku was also apparently goods friends with Korean Prince Asa (kanji unknown), a contemporary of his (from what Korean Kingdom? need citation). Shōtoku also maintained strong relations with many immigrants from mainland Asia. Among these was Hatano Kawakatsu (秦河勝), the leader of the Hata 秦 clan, a group of immigrants from central Asia (as far west as Assyria) who traveled along the silk road, and finally made their way to Japan via Korea and China in the 4th century. (Editor's Note: To people traveling east along the silk roads, Japan's Naniwa and Nara areas were the eastern terminus. Conversely, for Japanese people traveling west, Naniwa or modern-day Osaka was considered the gateway to Korea, China, and greater Asia.) Hatano was, by many accounts, an important counselor to Prince Shōtoku. Shōtoku's son, Yamashiro no Ōe no Ō 山背大兄王, took his name from the Yamashiro region in southern Kyoto where the Hata 秦 clan was established. This suggests that Shōtoku maintained strong relations with this and other immigrant communities.

|

|

|

Korean Carpenters and Early Japanese Temples

|

|

Korean Influence on Temple Architecture in Japan. Japanese prince Shōtoku Taishi (574-622 CE) employed workers from Korea's Paekche / Baekje 百済 or 百濟 (Jp. = Kudara) Kingdom to build Hōryūji Temple 法隆寺, which today remains one of the world's greatest extant treasure-houses of early Buddhist artwork and architecture in Japan. The temple's wooden pagoda and Golden Hall are considered masterpieces of 7th-century Paekche architecture.The temple in its heyday also housed people in adjacent areas where they studied the Buddhist teachings, art, and medicine. The original temple was destroyed, according to most records, in a fire in 670 CE, although much of its artwork was somehow saved. It was rebuilt, according to most scholars, soon thereafter by artisans from Korea's Paekche kingdom. Two other temples closely associated with Prince Shōtoku -- Hōrin-ji and Hōkiji -- were most likely built by artisans of Korea's Paekche kingdom. Another important early temple, Asuka Dera (see below), was also constructed by craftspeople from Paekche. Asuka Dera is generally regarded as Japan's oldest temple and claims to possess Japan's oldest Buddhist statue

First Temple Commissioned by Shōtoku Made by Koreans. Below text courtesy TIME MAGAZINE, Feb. 16, 2004. "Of the 202 Buddhist sanctuaries in Osaka's Tennōji 天王寺 neighborhood, there is one that stands out: Shitennōji 四天王寺, the first Japanese temple commissioned by a royal (Prince Shōtoku) and one of the oldest Buddhist complexes in Japan. Construction began in + 593, just decades after the religion reached the country's shores. One of the carpenters for Shitennōji, Kongō Shigemitsu 金剛重光, traveled to Japan from the Korean kingdom of Paekche for the project. Over a millennium-and-a-half, Shitennōji has been toppled by typhoons and burned to the ground by lightning and civil war -- and Shigemitsu's descendants have supervised its seven reconstructions. Today, working out of offices that overlook the temple, Kongō Gumi Co. 金剛組 is run by 54-year-old president Kongō Masakazu, the 40th Kongo to lead the company in Japan. His business, started more than 1,410 years ago, is believed to be the oldest family-run enterprise in the world. <end quote from Time Magazine> |

|

|

Korean Sculptural Styles Transmitted to Japan

|

|

|

Shaka Triad, 632 CE.

Attributed to Tori school.

Hōryūji Temple, Nara.

Click image to enlarge.

Sangokubutsu Style, Bronze

6th or 7th Century CE

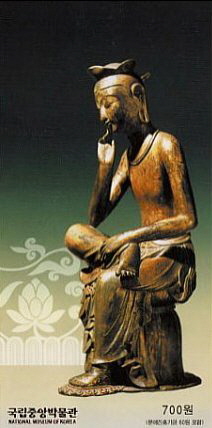

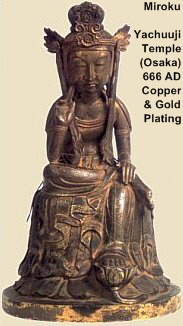

Miroku Bosatsu 半跏像弥勒

Toksugung Museum, Seoul

Phot from this J-site

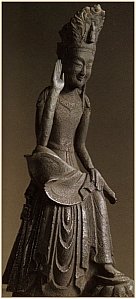

Shiragibutsu 新羅仏, Stone

Unified Silla Period (668–935 CE)

Known in Japanese as Keishū Sekkutsuan 慶州石窟庵

Photo from this J-Site

|

|

Korea's and Japan's earliest sculptures were greatly influenced by the artistic nuances of China's northern and eastern Wei 魏 kingdoms (late 4th to 6th centuries), which featured a marked frontality (with no concern for the sides or the back of the images), crescent-shaped lips turned upward, almond-shaped eyes, and symmetrically arranged folds in the robes. Japan was also influenced by Korean preferences for stock poses (see Miroku below), honeysuckle patterns, and softness of the brow ridge. In Japan, Buddhist images were made primarily by artisans of Korean or Chinese stock who lived in Japan. In Japan's Asuka-Hakuho period (538 to 710 CE), the mainstream works were attributed to Kuratsukuri no Tori 鞍作止利, a Chinese (some say Korean) emigrant who founded the Tori Busshi 止利仏師 school of early Buddhist sculpture in Japan. Statues make from his hand or by his apprentices are labeled as Tori Yōshiki 止利様式 or Tori Shiki 止利式. Art scholars agree that Tori-style sculpture was influenced by the earlier Buddhist art of China's Northern and Eastern Wei kingdoms, which was transmitted to Japan in large part by Koreans fleeing civil war on the Korean peninsula. Nonetheless, Tori's work communicates both softness and inner peace despite the stock poses, geometrical rigidity, and somewhat elongated facial and body features that characterized this period.

Small gilt-bronze statues (J = kondōzō 金銅像) were by far the most popular form of Buddhist art in Japan's Asuka-Hakuho period. Hundreds of bronze pieces, mostly gilt bronze, are still extant. The Asuka Era Photo Tour presents dozens of pieces from the 6th and 7th centuries. Viewing many of them in one glance gives us a good idea of the artistic styles then prevailing among the first wave of Korean and Chinese immigrant communities in Japan. These pieces allow us to surmise how Japan developed its own distinctive style. Also see the Techniques Page for details on casting and gilding methods. Wood statues too were mostly imported or copied from Korean and Chinese models, but it wasn't until the late 7th century that wood statues exceeded bronze sculptures in popularity in Japan.

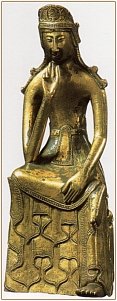

Sangokubutsu 三国仏 Statuary. Sangokubutsu literally means "Three Countries Buddha." Says JAANUS: "Buddhist statues made from the fourth to the seventh centuries in Korea. At that time, Korea was divided into three kingdoms; Koguryo (Goguryeo) 高句麗, Paekje (Paekche) 百済, and Silla 新羅. This period of Korean history is known in Japanese as the Sangoku Jidai 三国時代 (Three Countries Period), and Buddhist statues made during this period are known as Sangokubutsu 三国仏. The oldest of these kingdoms is Koguryo (J = Kōkuri or Kōguryo), which developed in the third century in the northern part of the Korean peninsular. Buddhist culture was received and absorbed from China, and Buddhist statues were produced showing a very strong Chinese influence. The Paekje 百済 Kingdom (J = Kudara) developed in the southwest part of the Korean peninsula around the mid-fourth century, and here too Buddhist statues were produced with a strong Chinese influence, received from the Chinese Fuyo culture. The Silla 新羅 Kingdom (J = Shiragi), with its capital in Kyongju, the east-central part of Korea, also became important in the mid-fourth century. Its culture developed closely in line with northern China, and there was direct interchange with the Chinese Ryo 梁 and Chin 陳 cultures, as well as with Kanan province (South China). An example of Sangokubutsu, considered to be a masterpiece of ancient Silla culture, is the bronze hankazō 半跏像 image (half-cross-legged Miroku Buddha/Bosatsu) in the Toksugung Museum in Seoul (J = Tokujugū 徳寿宮)." <end quote> See photo at right.

Shiragibutsu 新羅仏 Statuary. Says JAANUS: Shiragibutsu 新羅仏 is a style of Buddhist sculpture made during the period of Korean history when the Silla Dynasty (Jp. = Shiragi 新羅) defeated the Koguryo 高句麗 and Paekje 百済 Kingdoms and united the Korean Peninsula. This period is known in Japanese as Shiragi Tōitsu Jidai 新羅統一時代 (+654-935). The style of the sculpture was based on that of Tang Dynasty China (J = Tō 唐, 618-907 CE), combined with characteristic Silla simplicity and gentleness. The statue said to best represent this style is the stone statue known in Japanese as Keishū Sekkutsuan 慶州石窟庵, one of a number of shiragibutsu preserved in temples in Kyongju 慶州 (Jp; Keishū), the capital of Korea's Silla Dynasty. In addition to stone statues, shiragibutsu were also created in gilt bronze. Most are small figures (15-30 cm high) made in the late 8th and early 9th centuries, again using styles and techniques based on those of Tang China. <end quote> |

|

|

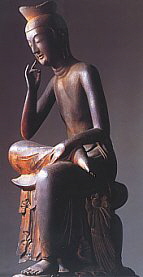

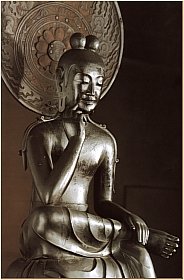

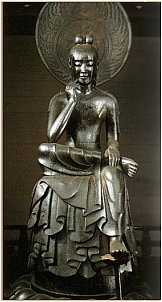

MIROKU BOSATSU / BUDDHA Strong Korean Influence

|

|

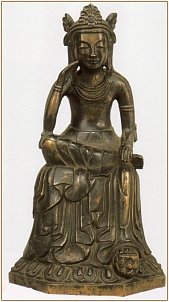

Miroku Bodhisattva / Buddha was one of the most popular deities in Korea and Japan in the early years. Hundreds of small gilt-bronze statues of Miroku were imported into Japan from Korea (and also China) and then copied endlessly by Japanese artisans and court-sponsored workshops. The style of these statuettes was influenced primarily by Korean models. Below are some examples.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Miroku Buddha / Bosatsu in Korean Art

半跏像 徳寿宮, early 7th century.

Photo Nat'l Museum of Korea and here.

|

Miroku Buddha / Bosatsu in Korean Art

半跏像 徳寿宮, early 7th century.

Photo Nat'l Museum of Korea and here.

|

Miroku Buddha/Bosatsu in Korean Art

H = 16.3cm, Gilt Bronze, 7th C.

Photo Tokyo Nat'l Museum

|

|

Miroku Bosatsu 弥勒菩薩

Copper with Gold Plating.

Kudara Kingdom 百済, Korea

7th Century, H = 16.4 cm.

Kanshō-in Temple 観松院, Nagano

Temple Web Site Here (Japanese Only)

|

Miroku Bosatsu 弥勒菩薩

Copper with gold plating.

Three Kingdoms Era

6th-7th Century AD

Hōryū-ji Temple (Nara)

H = 20.4 cm.

|

Miroku Bosatsu 弥勒菩薩

Copper with gold plating.

Three Kingdoms Era

6th- 7th Century AD

Hōryū-ji Temple (Nara)

H = 23.6 cm.

|

|

|

|

Miroku Bosatsu 弥勒菩薩, Wood

7th Century, Nat'l Treasure, Kōryū-ji

Temple, 広隆寺, Kyoto, H = 84.2 cm..

|

|

Miroku Bosatsu 弥勒菩薩

7th Century CE, Wood, Chūgū-ji

Temple 中宮寺 (Nara), H = 87 cm

|

Miroku Bosatsu 弥勒菩薩

Another view of image at left.

7th Century CE, Wood, Chūgū-ji.

|

Last two photos courtesy

Concise History of Japanese

Buddhist Sculpture (p. 15),

Bijutsu Shuppan-Sha

ISBN 4-568-40061-9

|

|

|

|

|

ASUKA DERA AND KOREAN MONKS IN EARLY JAPAN

|

The important Sanron School 三論宗 (literally Three Treatise School) of Buddhist philosopy was introduced to Japan around 625 CE by the Korean monk Hyegwan (Jp. = Ekan 慧灌, who hailed from the Korean kingdom of Kōkuri 高句麗 (often spelled as Koguryo or Goguryeo). Ekan resided at Gangōji Temple 元興寺 (aka Asuka Dera 飛鳥寺, a temple in Nara's Asuka district that was commissioned by the powerful Soga clan in the late 6th century and built by craftsmen from the Korean Kingdom of Baekje. Asuka Dera is generally regarded as Japan's oldest temple and claims to possess Japan's oldest Buddhist statue (see photo at right). The temple was constructed by craftsmen from the Korean kingdom of Baekje in 588 CE. It was relocated when the capital moved to Heijōkyō 平城京 (today's Nara city). Its Nara-city counterpart is known as Gangōji 元興寺, one of the Seven Great Temples of the Nara Period. In the decades prior to Hyegwan's arrival, Asuka Dera had been the home of two other important Korean monks. One hailed from the Korean Kingdom of Koguryo 高句麗 (Goguryeo) and was named Eji 慧慈 (えじ). The other hailed from the Korean Kingdom of Kudara 百済 (Paekche) and was named Esou 慧聡 (Esō えそう). Both served as teachers and mentors to Prince Shōtoku Taishi. Many resources, both English and Japanese, say all three lived at Asuka Dera, but none say they lived together at the same time, or that they actually met each other.

ABOUT THE ASUKA DAIBUTSU. The Asuka Buddha statue, says Asuka Historical Museum, "was the main object of worship (honzon) in the Asuka Dera's original Chū-Kondō 中金堂 (central main hall). It was cast in +609 (the 17th year of Empress Suiko's reign) by the master Busshi 仏師 (literally Buddhist teacher, master, or sculptor) known as Kuratsukuri no Tori 鞍作止利 (aka Tori-busshi), son of a Korean immigrant. (Editor's Note: Some sources say his grandfather immigrated from China, not Korea.) It is the oldest extant Buddhist image in Japan whose date of construction is definitely known. Repairs and alterations from later times are clearly in evidence, but in such features as the elongated face and the shape of the eyes may be seen the original characteristics of the Tori-shiki 止利式 (Tori style) of Buddhist imagery shared also by the Shaka Triad (see above photo) at Hōryūji Temple. |

|

|

Guze Kannon (Guse, Kuze, Kuse) 救世観音 or 夢殿観音

|

|

|

Guze Kannon (Guse, Kuze, Kuse)

Also called Yumedono Kannon

救世観音、夢殿観音

Hōryūji Temple 法隆寺, Nara

620 AD or so, 7th Century

H = 178.8 cm, made from a single block of wood = camphor (Kusu 樟)

Gold leaf (hakuoshi 箔押) applied over surface, and coronet and

other details made from gilt bronze.

Click to Enlarge

Click to Enlarge

|

|

This famous statue may be of Korean origin, but no concensus has been reached. Reportedly made in the image of Shōtoku Taishi, it is the earliest extant wooden statue in Japan (first half 7th century) and a designated national treasure of Japan. Carved from one piece of camphor 樟 wood, in the style of those times. Gold leaf is applied over the surface, and the coronet and other details are made from gilt bronze. The effigy is the non-esoteric form of Kannon, as Esoteric/Tantric Buddhism (Mikkyō 密教) did not arrive in Japan until the 9th century. Guze is also a name used for sculptures of the Asuka period, specifically for sculptures of a crowned Bodhisattva (J = Bosatsu) holding a jewel.

This statue was kept hidden for centuries inside the Yumedono Hall 夢殿 at Hōryūji Temple -- even the priests were forbidden from viewing the statue, which was wrapped in some 500 yards of white cloth. The practice of maintaining Secret Buddha (Jp. = Hibutsu 秘仏) most likely originated among Japan's esoteric sects (Shingon & Tendai) during the Heian period. The statue was finally unveiled in 1884, when the Japanese government allowed Ernest Fenollosa (1853-1908) and Okakura Tenshin 岡倉天心 (1863-1913) to discover its secrets. Fenollosa thought it to be of Korean origin. Some think it displays the style of Japan's Tori school of Buddhist sculptors who originally emmigrated to Japan from Korea and China. Today it is considered to be one of Japan's greatest art treasures for this period. It still remains a HIBUTSU at the temple, but for a small time every spring and fall it is open for viewing. <See JAANUS for more details on Guze Kannon>

GUZE KANNON MYSTERY? GUZE KANNON MYSTERY?

Below text by Henry Smith at Columbia University

From "Prince Shōtoku's Temple, The Riddles of Hōryūji"

Prince Shōtoku was, after all, like Shakyamuni (the Historical Buddha), a royal prince who renounced his inheritance in pursuit of spiritual ideals. Following Shōtoku's death in + 622, his family continued to patronize Hōryūji Temple until 643, when his son and heir, Prince Yamashiro Ōe no Ō 山背大兄王 (Yamashiro Ōji 山背王子 for short), was forced to commit suicide by the Soga clan leader, who was fearful of the threat that Yamashiro posed to Soga power. With this, the direct line of Prince Shōtoku came to an end. The temple survived, however, in close association with the memory of Shōtoku. But as far as we can tell, the Yumedono Kannon was never seen by anyone from the time of its consecration in the eighth century until 1884, when an inquisitive American scholar named Ernest Fenollosa managed to unwrap it. Fenollosa survived the catastrophe predicted by the priests of Hōryūji, but even today, the Yumedono Kannon is on public view for only a few weeks every year.

YUMEDOMO KANNON (aka Guze Kannon). Centuries of oral tradition confirm what you have probably already suspected, that this image is in fact a representation of Prince Shōtoku, now transformed into a saving Kannon. This association probably explains some very curious features of the statue. To begin with, the hands are overly large, and reach sensuously around what you may recall from the rooftop ornament: another reliquary, in effect, Prince Shōtoku seems to be holding his own remains. The face is equally unique, featuring a wide nose, prominent lips, and very narrow eyes, all said to be personal attributes of the prince himself.

But there is a very different school of thought which sees the smile as oriented outward, a sinister leer which threatens more than it saves, particularly when seen from below as the normal worshipper might. This has led to the eerie interpretation that the Yumedono Kannon is not a gentle and grace-giving Kannon, but rather the restless angry ghost of Prince Shōtoku himself. In support of such a theory consider a comparison between the Yumedono Kannon and the famous Kudara Kannon statue (also found at Hōryūji). The point of the comparison lies in the haloes. Whereas the halo of the Kudara Kannon is supported by a slender bamboo pole, that of the Yumedono Kannon is attached by a large nail driven into the back of the head. This highly unusual method of attachment, it is argued, is just like the voodoo technique of sticking pins in dolls, an effort to subdue the spirit of Prince Shōtoku rather than save it. This might also help explain why the image was kept wrapped up for so many centuries. The remaining mystery, however, is why the revered Prince Shōtoku should be so angry. The most persuasive theory is that his ghost was angered by the termination of his family line in + 643, when his son was forced to suicide by the Soga clan leader. <end quote from Henry Smith at Columbia University>

Shōtoku did dispatch envoys in 607 CE, all of them being of Korean descent who could read Chinese; the boat coasted the Korean shoreline as a direct passage was too dangerous. Ancient records report that the Chief Envoy (a Korean) asked the Chinese emperor to address Japan as "Land of the Sun" instead of "Land of Dwarfs," but this was not done until 670 CE (again at the suggestion of a Korean who felt the term insulted Japan). Nothing much with regard to the exchange of gifts from these early voyages is recorded in the Nihongi.(Carver and Covell 63)

In 621 CE Prince Shōtoku died in his sleep. As was the custom, Hye-che ordered a gilt bronze statue to be made "in the image of Prince Shōtoku." This statue became known as the "Dream Hall Kuanyin" or Yumedono Kannon. Probably this statue was placed in "The Dream Hall" of the first Horyu-ji. It was rescued by monks during the fire of 670 CE. For centuries this statue was considered "sacred" and was worshipped in a closed black lacquer case without being opened or unwrapped. In modern times, this statue is seen only once a year. When the statue was first unwrapped after many centuries, Ernest Fenollosa, an American enthusiast of Japan's traditional arts, particularly Buddhist pieces, remarked "Korean of course." Apparently Fenollosa felt that the statue was not "Japanese" and not "Chinese," and knowing the great influence of Korea on the Asuka-based kingdom, reached the only reasonable conclusion.

The "Dream Hall Kuanyin" is a little short of six feet. (Supposedly Prince Shōtoku was this tall, a descendent of 'Horseriders' from the north. These people were taller than ordinary Japanese at this time (5'3"). The gold leaf is in very good condition due to the fact that it was covered all those years. The statue has a two dimensional quality, has 'fins' or sawtooth-cutouts along the outer edges of the robe, a technique or mannerism begun by Wei-dynasty bronze casters. It possesses the most intricate bronze crown of any statue in Asia. It appears to be a mixture of several styles (all Korean) and designs; no known parallel exists with purely Japanese workmanship. Evidently it was shaped and cut out by a master craftsman, someone having a long tradition of metal technology behind him. The basic design was drawn from the tradition of the Horseriders, as evidenced by their objects in iron, bronze and gilt-bronze. Koguryo tomb painting also has similar designs, such as the "climbing flame," and the eagle with outstretched wings, plus a slightly modified honeysuckle pattern. The crown bears jewels of several types, the most noticeable being the lapis-like blue globes. These outline the figure of a human being in their placement. At the pinnacle of the crown stand onion-dome type cutouts, pieces which take the shape of the sacred fire of Buddhism. (This motif is shared by both Koguryo and Paekche.) The Dream Hall Kuanyin originally had pendants hanging from each side like the crowns unearthed in Kyongju tombs. The one on the left side of the head is preserved, but the other is missing. The face shows a softness of the brow ridge. It merges as naturally as possible into the forehead, as those of a lifelike person. The Korean eye and brow ridge together were to continue through Unified Silla even though the chubby-cheeked Buddhas of this period show Tang Chinese influence. (Carver and Covell p. 68) <end quotes from Henry Smith>

|

|

|

Kudara Kannon 百済観音, 7th Century

|

|

Hōryūji Temple 法隆寺, Nara. Designated National Treasure.

Wood (Gilded Camphor 樟) with Polychromy, H = 210 cm.

CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE.

Most scholars believe this statue (a national treasure) came from Korea or was made by Korean artisans living in Japan. The name of the statue -- Kudara Kannon 百済観音 -- literally means "Paekche Kannon." Paekche (Paekje 百済) was one of three kingdoms in Korea during this period, and Kannon is one of the most beloved Buddhist deities in Asia. The statue's extreme thinness seems at first bizarre, but the serenity in the face and the beautiful openwork bronze in the crown are marvelous. The vase symbolizes the "nectar" of Kannon's compassion -- it pacifies the thirst of those who pray to Kannon for assistance. There are many indications that the statue came from Korea (or was made by Korean artisans in Japan). The superior workmanship of the piece, plus many of the stylistic nuances (faint smile, slender face, thin body, folds in garment, halo) are all hallmarks of Paekche artisans and generally conform to artwork from Korea's Three Kingdom Period. In the book Korean Impact On Japanese Culture (Korea: Hollym International Corp., 1984), authors Jon Carter Covell and Alan Covell say the foremost clue of Paekche influence is the crown's honeysuckle-lotus pattern, which can also be found among the artifacts discovered in the tomb of Paekche's King Munyong (reigned 501-523 CE). The coiling of the vines, they say, plus the number of protrusions from the crown petals, are nearly identical to similar extant Korean pieces.

|

|

|

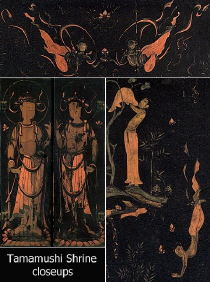

Tamamushi Shrine 玉虫厨子

|

|

Korean art presented to Japan, 7th Century, Wood

H = 226.6 cm W = 136.7 cm, Hōryūji Temple 法隆寺, Nara

Korean art presented to Japan. Says Ernest F. Fenollosa in Epochs of Chinese & Japanese Art: "Another great monument of 6th (or 7th century) Korean art is the Tamamushi Shrine, a miniature two-story temple made of wood, to be used as a reliquary, which was presented to the Japanese Empress Suiko 推古天皇 about 597 AD, and which still stands in perfect preservation upon the great altar at Hōryūji Temple 法隆寺 (Nara). The roof is finished in metal in the form of tiling. Lower story has painting on all four sides. Upper story opens with miniature temple doors, and is elaborately painted on the exterior. Long lanky Buddhist angels fly through the air. The finest paintings, and the best preserved, are the two tall thin Buddhist deities upon the doors, which show a relationship to the thin art of the Northern Wei. But the most striking feature about the shrine is the elaborate finish of all the corners and pillars and transverse beams with an overlay of plates of perforated bronze, which were probably gilded, the patterns of the perforation being among the finest specimens of the Korean power over abstract curvature." <end quote> NOTE: Today, Japan's scholars date this piece to sometime in the 7th century (to Japan's Nara Period). Zushi 厨子 is the Japanese word for a miniature shrine, wherein are kept Buddhist images or sutras 経.

|

|

|

Asuka Period Historical Notes, Political Setting

|

|

|

Bodhisattva

H = 16.3cm, Gilt Bronze,

7th C., Korea

Three Kingdoms Period

At Tokyo Nat'l Museum

|

|

The capital in those days was located in the Asuka district of the Yamato 大和 region (modern Nara prefecture), hence the era name. The early years are also referred to as the Suiko Period 推古時代, in reference to Empress Suiko 推古 who reigned from 592 to 628 AD. Her nephew was Prince Shoutoku, who is widely credited as the foremost patron of Buddhism in Early Japan. The capital in those days was located in the Asuka district of the Yamato 大和 region (modern Nara prefecture), hence the era name. The early years are also referred to as the Suiko Period 推古時代, in reference to Empress Suiko 推古 who reigned from 592 to 628 AD. Her nephew was Prince Shoutoku, who is widely credited as the foremost patron of Buddhism in Early Japan.

It was a period when professional artisans from Korea and China traveled to Japan in great numbers to teach the arts of carving and sculpture (and to escape political turmoil in their own lands, especially for Korean immigrants from the Kingdom of Kudara). These and other emissaries brought the Chinese written and spoken language, which remained the de facto language of the young Japanese nation until the 9th century. The introduction of the Chinese writing system in Japan, moreover, helped spread literacy, and resulted in the first great compilations of Japanese history, including the Kojiki 古事記 (Record of Ancient Matters) and Nihonshoki 日本書紀 (Chronicles of Japan). The Kojiki and Nihonshoki are considered by most scholars to be Japan's oldest surviving histories. Although compiled in the late Asuka period, they were not disseminated until the early years of the subsequent Nara era.

The late Asuka period is commonly referred to as the Hakuhou Period 白鳳時代 (646 to 710 AD), highlighted by the relocation of the capital to Naniwa 浪速 (in modern Osaka) and sweeping governmental changes following the Taika Reforms (Taika-no-Kaishin 大化改新) of 645 to 646 AD -- a turbulent time when the imperial court staged a coup to regain supremacy from the usurping Soga 蘇我 clan. These reforms abolished private ownership of land, distributed land more equally among farmers, appointed new governors in the provinces, and replaced the old tax structure with a new imperial tax system. The reforms were based largely on similar successful policies in Tang-dynasty China.

The entire period (from 538 to 710 AD) was marked by strong court patronage of Buddhism, the rapid construction of temples (which increased tenfold in the Hakuhou period), the arrival of countless artisans, priests, and scholars from Korea and China, the creation and copying of numerous works of Buddhist art, and numerous Japanese missions (outside link) dispatched to China. Buddhism brought new theories on government, a means to establish strong centralized authority, a system for writing, advanced new methods for building and for casting in bronze, and new techniques and materials for painting. Buddhism was, in most respects, adopted by Japan's rulers primarily to establish social order and political control, and to join the larger and more sophisticated cultural sphere of mainland Asia. Despite early resistance to the imported Buddhist faith, Buddhism made strong headway among the court and upper classes, but had minimal impact on the common people.

Japanese art until the 9th century is primarily "religious" art, confined to temple construction, Buddhist sculpture, painting, illustrated hand scrolls to transmit Buddhist teachings, and mandalas of the Buddhist cosmos and its deities. I have yet to study the Asuka Period in depth, but it is clear that guilds of professional Japanese craftsmen (those who carved the statues) began to emerge soon after Buddhism's transmission to Japan. The most important surviving temples from the Asuka period are Hōryūji (Horyu-ji) Temple 法隆寺 (Nara), Shitennō-ji Temple 四天王寺 (Osaka), and Yakushiji Temple 薬師寺 (Nara). All are modern-day treasure houses of Japan's earliest Buddhist artwork. NOTE: Japan's break with China in the late 9th century provides an opportunity for a truly native Japanese culture to flower, and from this point forward indigenous secular art becomes increasingly important. Religious and secular art flourish in step until the 16th century, but then the importance of institutionalized Buddhism plummets owing to the Confucian ethic of the Edo-period shogunate, contact with the Western world, and political turmoil. Secular art becomes the primary vehicle for expressing Japanese aesthetics, but it is tempered greatly by the "spontaneity" of Zen Buddhism and the "affinity to nature" of Shinto. Nonetheless, generally and overall, Buddhist sculpture slips into decline after the Kamakura era.

|

|

|

Emperor's remark pours fuel on ethnic hot potato

|

|

Story by staff writer HIROSHI MATSUBARA, Japan Times March 11, 2002. "A surprise remark by Emperor Akihito in December shed light on deep historical and ethnic ties that bind Japan and the Korean Peninsula, but contrasting media reactions highlighted a difference in historical perception across the Sea of Japan. During a news conference to mark his 68th birthday, the Emperor drew the public's attention to a historical document that shows one of his eighth-century ancestors was born to a descendant of immigrants from the Korean Peninsula. In doing so, he said he felt a close "kinship" with Korea. His remark received a warm welcome in Seoul, marking as it did the first time a member of the Imperial family publicly noted the family's blood ties with Korea. In his first public address this year, South Korean President Kim Dae Jung accordingly praised the Emperor for his "correct understanding of history." During a meeting with members of the Imperial Household Agency press club prior to his birthday on Dec. 23, the Emperor, quoting from the "Shoku Nihongi" ("Chronicles of Japan"), compiled in 797, said the mother of Emperor Kanmu (737-806) had come from the royal family of Paekche, an ancient kingdom of Korea.

|

|

RESOURCES & NOTES

- Flammarion Iconographic Guides, by Louis Frederic, ISBN 2-08013-558-9. Abridged quote: "The earliest sculpted images appearing in China were copied from imported models (probably from Gandhara, India) in the first century. These images, until the 4th or 5th century, were typically carved into solid rock, on the walls of caves and holy places. Most images were carved in high relief, to be viewed from the front. Images from China's WEI period portrayed the Buddhist deities with wide forheads, sharp bridged noses, small mouths, slim bodies, and facial attitudes both stiff and majestic. This so-called WEI style was a major influence on the early sculptural traditions of both Korea and Japan. Clay was the preferred material in China until the sixth century, but the Chinese also produced numerous bronze pieces in the same style. By the Tang period, however, Chinese Buddhist statuary had distanced itself somewhat from the styles of India, and began to portray the Buddhist divinities with greater realism, supple attitudes, fuller forms, clothed in flowing garments, and decked in ornaments (bracelets, jewels, etc.) The decorative art of the caves continued to predominant, and smaller statuary made from bronze, wood, or stone became less frequent. By the late 9th century, the art of sculpture fell into decline, overshadowed by a preference for paintings. After the persecutions of 845 AD, Buddhist sculptural art in China fell into decadence, with the same early copies ceaselessly reproduced, often with mediocre results. The early sculptural style of Korea adhered closely to the Chinese models, but the Koreans were more enamored by the divinities from the estoric schools, and the images they produced strongly influenced the Japanese tradition." <end abridged quote>

- Art Tour of Japan's Asuka Era (A-to-Z Photo Dictionary)

- Sculptors and Art of Japan's Asuka Era (A-to-Z Photo Dictionary)

- Korean Impact On Japanese Culture (Korea: Hollym International Corp., 1984), authors Jon Etta Hastings Carter Covell and Alan Covell.

- Transmitting the Forms of Divinity: Early Buddhist Art from Korea and Japan. Comparing Korean and Japanese Buddhist art, this volume explores the cultural, ideological and artistic exchange between the two countries during the 6th-9th centuries, when Buddhism took hold throughout northeast Asia. Buddhist sculptures in gilt bronze, wood and stone are the main focus of this work, which contains essays by Korean, Japanese and American scholars.

- Korean History Project by William Caraway

- The Collected Works of Korean Buddhism. This edition, completed in July 2012, consists of thirteen volumes of English translations of selected texts from the Hanguk Bulgyo Jeonseo 韓國佛教全書. The thirteen volumes of this anthology collect the whole panoply of Korean Buddhist writing from the Three Kingdoms period (ca. 57 C.E.‒668) through the Joseon dynasty (1392‒1910). These writings include commentaries on scriptures as well as philosophical and disciplinary texts by the most influential scholiasts of the tradition; the writings of its most esteemed Seon adepts; indigenous collections of Seon gongan cases, discourses, and verse; travelogues and historical materials; and important epigraphical compositions. Participating translators: Juhn Ahn, Robert Buswell, Michael Finch, Jung-geun Kim, Charles Muller, John Jorgensen, Richard McBride, Jin Y. Park, Young-eui Park, Patrick Uhlmann, Sem Vermeersch, Matthew Wegehaupt, and Roderick Whitfield.

- READING LIST: KOREAN INFLUENCE IN JAPAN

Below list courtesy K12 Class Syllabus of Marymount School

- Catalogue: Kyongju and the Silk Road. Korea: Kyongju National Museum, 1991.

- Catalogue: A Search for the Light of the East - Silk Road and Korean Culture. Korea: Kyongju World Expo., 2000.

- Catalogue: Gyeongju National Museum.

- Covell, Jon Carter and Covell, Alan. Korean Impact On Japanese Culture. Korea: Hollym International Corp., 1984.

- Kim. Young-Joo. Kyongju, Old Capital of Shilla Dynasty Enlivened with 2000-year History. Seoul: Woo Jin Publishing Co., 2000.

- Portal, Jane. Korea Art and Archaeology. New York: Thames and Hudson, Inc., 2000.

- Yi, Kun Moo. National Museum of Korea. Seoul: National Museum of Korea, 1998.

- Lucky Seventh: Early Horyu-ji and Its Time by J. Edward Kidder, Jr.

First Published July 2012

|

|