|

|

|

|

TENGU

The Slayer of Vanity

Origins: India + China + Japan

Tengu 天狗 are mountain and forest goblins with both Shinto and Buddhist attributes. Their supernatural powers include shape-shifting into human or animal forms, the ability to speak to humans without moving their mouth, the magic of moving instantly from place to place without using their wings, and the sorcery to appear uninvited in the dreams of the living.

The patron of martial arts, the bird-like Tengu is a skilled warrior and mischief maker, especially prone to playing tricks on arrogant and vainglorious Buddhist priests, and to punishing those who willfully misuse knowledge and authority to gain fame or position. In bygone days, they also inflicted their punishments on vain and arrogant samurai warriors. They dislike braggarts, and those who corrupt the Dharma (Buddhist Law).

The literal meaning of Tengu is "Heaven 天” and “Dog 狗." In Chinese mythology, there is a related creature named Tien Kou (Tiangou 天狗), or "celestial hound." The name is misleading, however, as the crow-like Tengu looks nothing like a dog. One plausible theory is that the Chinese Tien Kou derived its name from a destructive meteor that hit China sometime in the 6th century BC. The tail of the falling body resembled that of a dog, hence the name and its initial association with destructive powers.

Historical Notes. Tengu mythology was probably introduced to Japan in the 6th or 7th century AD, in conjunction with the arrival of Buddhism from Korea and China. These goblins thereafter appear in Japan’s ancient documents (e.g., from around 720 AD), and are closely associated with Mount Kurama in Japan (near Kibune), the abode of the legendary white-haired Sōjōbō (Sojobo) 僧正坊, King of Tengu. In Myths and Legends of Japan (1913; by F. Hadland Davis), the Tengu are said to emanate from the primordial Japanese god Susano-o. Tengu lore can be found not just in Buddhist circles, but also among Shinto, Budo, and Ninpo groups. As late as 1860, the Edo Government was posting official notices to the Tengu, asking the goblins to temporarily vacate a certain mountain during a scheduled visit by the Shogun (see Japan and China, by Captain Brinkley). see de Visser’s report.

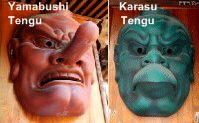

(L) Karasu Tengu (R) Yamabushi Tengu

Lanterns on Festival Float, Dontsuku Festival, Inatori City

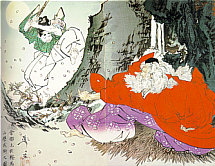

Crow Tengu Riding Boar (Karasu Tengu 烏天狗騎猪)

Color on Silk, Hanging Scroll, H = 43.8 cm, W = 54.9 cm

Late Edo Period Painting by Kaihō Yūtoku, Sairin-ji Temple 西林寺, Kyoto.

Photo from Faith and Syncretism: Saichō and Treasures of Tendai. Kyoto National Museum catalog, 2005.

|

In paintings and woodblock prints, the boar often appears as the steed of the tengu or of their king, Sōjōbō 僧正坊. Sōjōbō is closely linked to famed warrior Minamoto no Yoshitsune 源義経 (1159-1189), one of Japan's most revered samurai. In a well-known legend, Yoshitsune lived among the tengu in his youth and received training in the arts of war from Sōjōbō himself. <Note: The Buddhist martial deity Marishiten is also often shown riding atop a boar.> Another possible interpretation of the above image relates to the following Zen story: “One day a hunter was in the mountains when he happened to see a snake killing a bird. Suddenly a boar appeared and began to devour the snake. The hunter thought he should kill the boar, but changed his mind because he did not want to be a link in such a chain, and cause his own death by the next predator to come along. On his way home he heard a voice call to him from the top of a tree. It was the voice of a tengu. It told him how lucky he was, for had he killed the boar, the tengu would have killed him. The man subsequently moved into a cave and never killed another animal.” <Sources: A Field Guide to Demons, Fairies, Fallen Angels, and Other Subversive Spirits (by Carol Mack, Dinah Mack) and Animal Motifs in Asian Art: An Illustrated Guide to Their Meanings and Aesthetics (by Katherine M. Ball).>

|

|

|

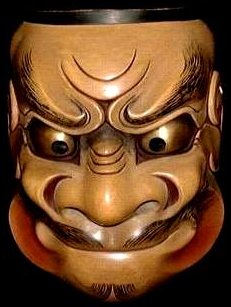

Noh Mask

Yamabushi Tengu

(pride-fallen monk)

|

|

Tengu Origins

Below text courtesy of JAANUS

Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System

http://www.aisf.or.jp/~jaanus/deta/t/tengu.htm

Literally celestial dog. A bird-like goblin frequently encountered in Japanese folk-beliefs, literature and their pictorial depictions. The Japanese demons derive the name from the Chinese mountain god Tiangou 天狗, but also are related to the winged Buddhist deity Garuda (Jp. = Karura). Furthermore, tengu are seen as transformations (Jp : keshin 化身) of Shinto deities, yama no kami 山の神, mountain guardians often associated with tall trees. Tengu are of two physical types: karasu tengu 烏天狗 identified by a bird's head and beak; and konoha tengu 木の葉天狗 distinguished by a human physique but with wings and a long nose (also called yamabushi tengu). This type of tengu often carries a feather fan in one hand. Because of its long nose, tengu are associated with the Shinto deity Sarudahiko (Sarutahiko) 猿田彦 who takes on the visage of a monkey, and tengu masks play a prominent role in some religious festivals. Early Japanese popular tales such as those in the KONJAKU MONOGATARI 今昔物語 (early 12c) portray tengu as enemies of Buddhism, setting fires at temples or tricking priests. Priests who attain special powers through religious discipline, but use these powers for their own ends were thought to enter in the next life the transmigratory realm of tengudou 天狗道. The earliest representations of tengu are in Kamakura-period emaki 絵巻, such as the "Tengu zoushi emaki 天狗草紙絵巻" of 1296 (Nezu 根津 Museum), which criticize arrogant priests who end up becoming tengu. According to legend, as a boy the famous warrior Minamoto no Yoshitsune 源義経 (1159-89) trained in magical swordsmanship with the tengu king Soujoubou 僧正坊 near Kuramadera 鞍馬寺 in the mountains north of Kyoto (see photo below). Tengu frequently are shown in pictures concerning the life of Yoshitsune, including both the Hogen-Heiji 保元平治 battle screens (Metropolitan Museum) and depictions of "Hashi Benkei 橋弁慶" or “Benkei at the Bridge" theme. The Momoyama-period daimyo 大名 Kobayakawa Takakage 小早川隆景 (1532-90) supposedly held dialogues with the tengu king Buzenbou 豊前坊 on Mt. Hiko 彦 (see photo below).

The character of tengu gradually changed over the centuries. For instance, tengu were long thought to abduct children, but by the Edo period they often were enlisted to aid in the search for missing children. Similarly, tengu became temple guardians and sculpted images of them were placed on or around temple buildings. Tengu also are associated with yamabushi 山伏 or "mountain ascetics," whose form they often assumed. Tengu often are depicted wearing the yamabushi's distinctive cap and robe. Illustration of tengu increased in popularity and variety during the Edo period, usually reflecting the more positive and even light-hearted conception of the once-ferocious demon. In particular, the long nose of the tengu carried both comic and sexual meaning in ukiyo-e 浮世絵 prints. <end quote by JAANUS>

NOTES ON ORIGIN OF TENGU. Says F. Hadland Davis in his 1913 book Myths and Legends of Japan: “There are other confusing traditions in regard to the word Tengu, for it is said that the Emperor Jomei gave the name to a certain meteor ’which whirled from east to west with a loud detonation.’ Then, again, a still more ancient belief informs us that the Tengu were emanations from Susaono-o, the Impetuous Male, and again, that they were female demons with heads of beasts and great ears and noses of such enourmous length that they could carry men on them and fly with their suspended burden for thousands of miles without fatigue, and in addition their teeth were so strong and so sharp that these female demons could bite through swords and spears.”

|

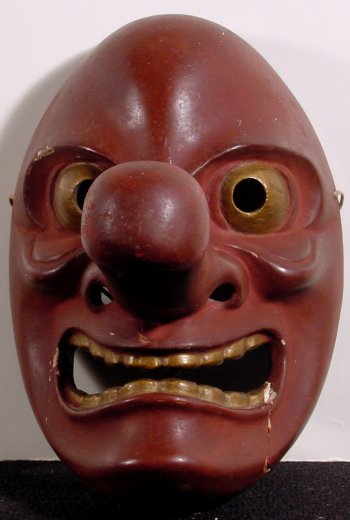

Karasu (crow) Tengu

Hanzobo Shrine, Kamakura

Yamabushi Tengu

Pride-fallen monk

Hanzōbō 半僧坊,

Kamakura, Japan

TYPES OF TENGU

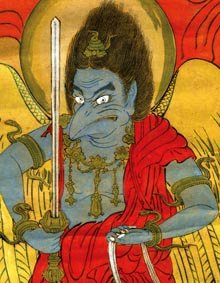

Daitengu 大天狗 (Major Tengu or Yamabushi Tengu). Symbol of fallen monks or warriors, whose arrogance and pretentiousness angered the Tengu. Portrayed as a tall man with long nose, red face, wearing garb of hermit or priest, with small hat that serves as a drinking cup; with or without wings, but always able to fly; sometimes wearing geta (wooden sandals), holding a magic fan made of bird feathers (when used, can make hellish winds), carrying a staff (bo/jo) or small mallet.

Kurama Tengu (Tengu of Mt. Kurama 鞍馬). Home of the white-haired and ancient Sōjōbō 僧正坊, King of the Tengu. Mt. Kurama is located north of Kyoto.

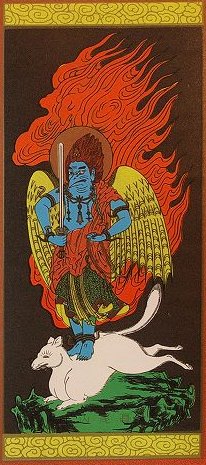

Karasu Tengu 烏天狗

(Crow Tengu, Minor

Tengu or Kotengu)

The most ancient form, these crow-like goblins now serve the Daitengu Yamabushi Tengu.

|

|

Tengu Evolution Tengu Evolution

The Tengu has evolved in both appearance and purpose over the centuries. Originally portrayed as an evil crow-like creature with a man’s body, a beaked face, a small compact head, feathered wings, and heavy claws, the Tengu has since evolved into a protective bird-like man-goblin with an uncommonly long nose, wearing a small monk hat, and oft-times sporting a red face. Patrons of the martial arts, Tengu are credited with exraordinary skills in sword fighting and weapon smithing. They sometimes serve as mentors in the art of war and strategy to humans they find worthy. Tengu live in colonies under the leadership of a single Tengu, who is served by messenger Tengu (usually Karasu). More mischievous than evil, the Tengu are hatched from eggs like birds.

Karasu Tengu (“Crow” Tengu) 烏天狗

The ancient form of the Tengu was the “karasu” or “crow” Tengu. Portrayed as an evil crow-like creature with the body of a man, it was capable of kidnapping adults and children, starting fires, and ripping apart those who willfully damaged the forest, for the Tengu live in trees. Sometimes, too, the Tengu would abduct human beings, only to release them later, but the “lucky” survivor would return home in a state of dementia (called “Tengu Kakushi, meaning “hidden by a Tengu”).

Yamabushi Tengu (Mountain Monk) 山仏師 天狗.

Over the centuries, the Tengu becomes more human in appearance and takes on a protective role in the affairs of men. The Tengu can transform itself into a man, woman, or child, but its prefered disquise is to appear as a barefooted, wandering, elderly mountain hermit or monk (yamabushi) with an extremely long nose. Both the magical tanuki (badger) and oinari (fox) can also change to human form, and in some Japanese traditions these two creatures are actually considered to be animal manifestations of Tengu.

The Yamabushi Tengu comes in two flavors -- the long-nosed goblin with human face or the beak-nosed goblin with human face.

The Buddhist Connection. Why the Long Nose?

Tengu are always portrayed as having a mischievous sense of humor, for they love playing tricks on those they encounter, especially on pretentious and arrogant Buddhist priests and samurai. Indeed, by the late Kamakura Period, the Tengu become a major literary vehicle for criticising both established and nascent Buddhist sects (see RESOURCES below for more).

The long nose relates to the Tengu’s hatred of arrogance and prejudice. Priests with no true knowledge, prideful individuals, those attached to fame, and those who willfully mislead or misuse the Buddhist cannons are turned into the long-nosed Yamabushi Tengu (or sent to Tengudo, the realm of the Tengu) after their deaths. Corrupt Buddhist monks and corrupt Buddhist monestaries were in fact a major concern throughout Japan’s middle ages. Tengu are thus seen as protectors of the Dharma (Buddhist law), and punish those who mislead the people. Over time, the folklore of tengu and yamabushi become intertwined, and even the crow tengu (karasu tengu) begin wearing the robes and caps of priests. The long nose relates to the Tengu’s hatred of arrogance and prejudice. Priests with no true knowledge, prideful individuals, those attached to fame, and those who willfully mislead or misuse the Buddhist cannons are turned into the long-nosed Yamabushi Tengu (or sent to Tengudo, the realm of the Tengu) after their deaths. Corrupt Buddhist monks and corrupt Buddhist monestaries were in fact a major concern throughout Japan’s middle ages. Tengu are thus seen as protectors of the Dharma (Buddhist law), and punish those who mislead the people. Over time, the folklore of tengu and yamabushi become intertwined, and even the crow tengu (karasu tengu) begin wearing the robes and caps of priests.

|

|

by Yoshitoshi Tsukioka (1838-1892)

|

SOJOBO, TENGU KING

Sōjōbō 僧正坊

In a well-known legend, the hero of medieval Japan, Minamoto Yoshitsue, is trained in sword fighting by white-haired Sōjōbō, the Tengu King of Mt. Kurama, who befriends him. Yoshitsune later becomes the great warrior of lore, helping his brother Yoritomo defeat the Taira Clan to establish the Kamakura Shogunate.

|

|

|

In this detail of a woodblock print by Yoshitoshi, the martial arts master Tsukahara Bokuden receives divine instruction in the art of fencing from a mysterious yamabushi (mountain priest) tengu named Enkai of Haguro Mountain. Print from the collection of Charles C. Goodin and featured at the Yoshitoshi Ukiyo-e Web Gallery in the Eastern Brocade Series.)

Click here to see Charles C. Goodin's Tengu Lore Page

|

|

|

The Tengu of Mout Hiko appears out of the mist to enlighten the swordsman Kobayakawa Takakage, in this print by Yoshitoshi. (Print featured at the Yoshitoshi Ukiyo-e Web Gallery in the Ghost Series). Says Goodin: “What I found most interesting was that the scene was shown from the tengu's perspective, that is, from his side of the mist. Through breaks in the mist, Kobayakawa can be seen sitting composed ready to receive the tengu's message while his men recoil in fear.”

|

|

|

Tengu images at

Yakuōin Temple (Mt. Takao).

Located near Tokyo, Japan.

高尾山 ・藥王院

More Photos Below

|

Karura (Garuda) Folk Mask

Don’t confuse the bird-man Karura

with the Karasu Tengu. Though similar in

appearance, Karura is servant to

Vishnu (Hindu lord). In Japan, Karura is

one of 28 Attendants to Senju Kannon.

<Buy mask online>

|

|

Large tengu floats for use

in the annual Dontsuku

Fertility Festival in Inatori, Japan

|

Tengu Images from Yakuōin Temple, Mt. Takao

Photos by Lisa A. Scheinin. Click any image to view larger photo.

(L) Karasu Tengu and (R) Yamabushi Tengu

Yakuōin Temple, Mt. Takao, Photos by Lisa A. Scheinin

Click either image to view larger photo

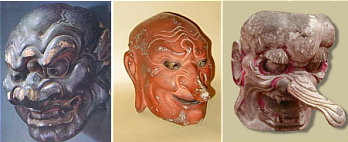

L to R (Ancient Mask Nara Period, Edo Period, Edo Period)

Mask images from various web stores at trocadero.com

|

Yamabushi Tengu, Wooden Noh Mask

courtesy thetengu.com/tengu

|

Beshimi Tengu (Noh Mask)

Beshimi means mouth clamped firmly shut.

|

|

Tengu Noh Mask

from savvycollertor.com online store

|

Made in 1770 by

Daibusshi Tanaka Mondo 大仏師 田中主水

妙覚 道了大権現 尊像

寅正月中浣

大仏師 田中主水彫造

<前住・大崇道豊代>

Photo this J-site

|

|

道了大権現 道了大権現

Dōryō Daigongen (Doryo, Douryou)

In 2005, scholar Duncan Williams published “The Other Side of Zen: A Social History of Soto Zen Buddhism in Tokugawa Japan.” Chapter Four of this book, entitled “The Cult of Doryo Daigongen: Daiyuzan and Soto Prayer Temples” forces us to overcome the traditional boundaries of Buddhist scholarship to examine the emergence of a popular cult and its links with the mountain ascetics and Shinto. The “great avatar Doryo (Douryou)” 道了大権現 had been a mountain ascetic before becoming a Soto Zen monk, and was eventually appointed as head cook and administrator at Daiyūzan Temple 大雄山 (Kanagawa Prefecture). However, upon his death in 1411 AD, he vowed to become the guardian of the monastery and he is believed to have metamorphosed into a TENGU 天狗 (a goblin; this site page). According to legend, “his body was then engulfed in flames as he appeared transformed and stood on a white fox to promise a life free from illness and full of riches for those who sincerely worshipped him (p. 62).” Here, the legendary anecdote leads to a detailed analysis of how since the 17th century this became linked to the mass production and sale of the Doryo (Douryou) talisman. Another related phenomenon is that of pilgrimage to this sacred site (Daiyūzan Temple), highlighted through the concrete evidence provided by stone markers. It allows the author to determine that these pilgrimages “took off from the mid-1860s (p. 69). < Above review from the Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 33/1 (2006, pages 176, written by Michel Mohr, Doshisha University. Duncan Williams’ book published by Princeton University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-691-11928-7. >

道了大権現 道了大権現

MORE ON DOURYOU DAIGONGEN

TENGU WHO BECOMES A BOSATSU

Daiyuzan Saijoji (Soto Zen Temple)

forum.japanreference.com

Once I entered the monastery gates I was awestruck. What a magnificent place. I had a walkabout to see as much as I could before heading to the sign-in desk for the sesshin. This mountain that the monastery was built on was very famous, as I came to find out, for its Tengu (mountain spirit) named Doriyo (editor here: this is an incorrect English spelling). As the myth goes, a young monk came to settle upon this mountain many centuries ago, he was determined to build a temple there but soon found that he could not do it on his own. This is when he met the long nosed, winged, tengu named Doriyo. After receiving the teachings of the monk, Doriyo was so moved that he vowed to help build Saijoji Temple with his magical feats of strength and energy. Doriyo then lifted a huge boulder and threw it to the center of the clearing stating this will be the foundation. Today if you visit this monastery you will see the boulder wrapped in protective Shinto ropes sitting in the middle of the compound. Nearby there is a well, with water that is said to have miraculous healing powers. People come from all over Japan to fill their plastic jugs with this water, and take it home with them. At the top of the compound there is a shrine for Doriyo where it becomes clear that he has been elevated from Tengu status to that of Bodhisattva (Bosatsu) status. The monks referred to him as Doriyo Bosatsu. Giant Getta (wooden slippers) adorn the outside of the shrine. Some were as big as a golf cart.

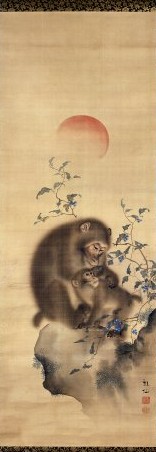

SARUTAHIKO 猿田彦, 猿田彦神 SARUTAHIKO 猿田彦, 猿田彦神

Also written SARUTABIKO, SARUTAHIKO-NO-KAMI, SARUDAHIKO. Commonly translated as “monkey man.” The long-nosed Shinto deity of the crossroads who takes on the visage of a monkey; also considered by some to be the ancestor of the long-nosed Tengu mountain goblin.

The celestial Shinto goddess Ame-no-Uzume-no-Mikoto (天宇受売命; the “terrible female of heaven”) was the first to meet the earthly kami named Sarutahiko. She determines that he is not an enemy, after which he guides Ninigi 彦火瓊瓊杵尊 and other Shinto deities on their descent from heaven to earth. She is accorded honors by Ninigi for her encounter with Sarutahiko -- she becomes the founder and head of the Sarume Order of sacred Shinto dancers, for she and her lineage are henceforth christened Sarume-no-Kimi (猿女の君 monkey women). Writes W.G. Aston: "The Sarume were primarily women who performed comic dances (saru-mahi, 猿樂, monkey dances) in honor of the Shinto Gods. They are mentioned along with the Nakatomi and Imbe as taking part in the festival of first-fruits and other Shinto ceremonies. These dances were the origin of the Kagura 神楽 and the No performances" <end Aston quote>

Sarutahiko and Sarume-no-Kimi are both personified in medieval kagura 神楽 dances and sarugaku 申楽 shows, and even today appear in popular forms of entertainment. Ame-no-Uzume, moreover, is the same Shinto goddess whose erotic and humorous dance prompted Amaterasu to come out from her cave to bring light back into the world. Click here (outside site) for more on Shinto mythology found in the Kojiki 古事記 (Japan's oldest surviving text; 712 AD) and the Nihongi 日本紀 (Chronicles of Japan; 797 AD).

Sarutahiko Mask

Modern

Takachiho-cho

Okagura Theater

Photo Hiroaki Sasaki

|

Monkey painting by

Japanese artist

Mori Sosen, Edo Era

Photo courtesy

the British Museum

|

|

SARUTAHIKO’S DEATH SARUTAHIKO’S DEATH

Below text courtesy Encyclopedia of Shinto

Sarutahiko is an earthly Shinto kami who went out to the "eight crossroads of heaven" to meet and act as guide to the heavenly Ninigi (aka Hiko-ho-no-ninigi no Mikoto 彦火瓊瓊杵尊, the August Grandchild of Heaven) at the time of Ninigi’s descent to earth. Sarutahiko was described as having a fantastic appearance, with a nose seven spans long, a height of over seven feet, and with eyes that glowed red like a mirror. Since the goddess kami Ame no Uzume 天宇受売命 was the first to confront Sarutahiko, Ninigi granted to her the clan title Sarume no Kimi 猿女の君 (monkey woman). After acting as guide to Ninigi, Sarutahiko arrived at the upper reaches of the Isuzu River in Ise, where the Kojiki 古事記 (Records of Ancient Matters; Japan's oldest surviving text; 712 AD) records that his hand became trapped inside a large clam at Azaka, and he thus drowned. He is considered the ancestor of the Ujitoko clan in Ise, and the central object of worship (saijin) at the Sarutahiko Shrine 猿田彦神社 located in Ise, Mie Prefecture. During the Tokugawa period, he was also adopted as the "ancestor of teaching" in the school of Suika Shinto. <end quote by Kadoya Atsushi, Encyclopedia of Shinto>

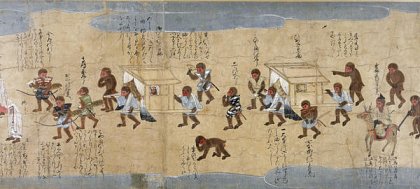

SARUTAHIKO, SANNOU, & BUDDHISM

Sarutahiko’s connection with the Koushin 庚申 ritual and three-monkey worship did not occur until the Edo period, which reflects the growing importance of Shinto beliefs during the Edo era. Nonetheless, Sarutahiko appears in earlier legends surrounding SANNOU 山王, the mountain king and central deity of the the Tendai Shinto-Buddhist multiplex at Mt. Hiei, whose avatar is the monkey. In the Scroll of the Monkey (猿の草子), produced sometime around 1570 AD, the longest passage is called the Hiei Engi (比叡縁起), which discusses the origin of Buddhist practice on Mt. Hiei.

First, Shaka (the Historical Buddha), while still living in the Tosotsu-ten (兜率天, Skt: Tusita; Buddhist heaven), creates the land in which he intends to propagate the Buddhist doctrine after his appearance in this world. Second, at the time of Ugaya Fukiaezu no Mikoto (鵜草葺不合尊; the father of Emperor Jinmu 神武), Shaka obtains the land at the foot of Mt. Hiei from an old fisherman at the intervention of Yakushi Nyorai. Shirahige (白髭), the old fisherman, the Shinto kami who has to yield his land to Shaka, is none other than Sarutahiko-no-kami (猿田彦神), who in the myths of the Kojiki 古事記 meets Hiko-ho-no-ninigi no Mikoto (彦火瓊瓊杵尊) then on his descent from the heavens) and pledges to guide him on his way. Third, around the year 800 AD, SANNOU is revealed to Saichou 最澄, the founder of the Tendai sect. <Above paragraph quoted from article entitled Saru no Soshi in the Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1996 23/1-2. Story by Lone Takeuchi.>

Saru no Soshi (猿の草子 Scroll of the Monkey)

Late 16th Century, One Section of the Japanese Scroll

Photo courtesy of British Museum, where the scroll is kept.

For much more on monkey lore, click here.

TENGU. Says Hiroaki Sasaki: Over time, the Shinto deity Saruta-biko no Mikoto became the god for good journey and the ancestor of the super beings called " Tengu," who live deep in the mountains. The Tengu are considered as agile as "saru" (monkies). There are many legends that the great swordsmen of Japanese history learned their skills in the martial arts from Tengu tutors. Legend says that Minamoto-no-Yoshitsune, when a child, learned martial arts with the king of the Tengu at Mt. Kurama in Kyoto.

WORKSHEET -- BELOW NOT YET COMPLETED

Three Tengu of Japan = Nihon Sandai Tengu 日本三大天狗 (aka Sandai Myōgi Tengu 三大妙義天狗)

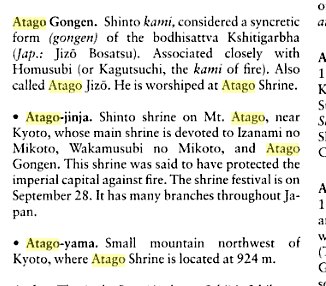

- Tengu Tarōbō 天狗太郎坊. Main deity of Mt. Atago 愛宕 (NW of Kyoto), worshipped as a protector against fire disasters; the Shintō avatar of the hybrid Buddhist-Kami deity known as Shōgun Jizō Bosatsu. http://eos.kokugakuin.ac.jp/modules/xwords/entry.php?entryID=777. The area flourished as a sacred Shugendō site and kami cult. Moreover, because Shōgun Jizō (the battle-victory Jizo Buddha) was worshipped as the Buddhist avatar (honji butsu) of Atago, the Atago kami was popular with the warrior class as a "military kami" (gunshin) in the medieval period. Also known as the God of Victory. According to local legend, a 9th-century monk named Kakimoto 桓本, said to have been a pupil and friend of Kōbō Daishi 弘法大師, grew proud of his great religious knowledge and eventually turned into Japan's first Daitengu 大天狗 (Great Tengu). Also known as Atago Gongen 愛宕権現 or Atago Daigongen 愛宕大権現.

- Tengu Sōjōbō 天狗僧正坊 of Kurama-yama (Mt. Kurama 鞍馬山) near Kuramadera Temple 鞍馬寺 in the mountains north of Kyoto. Sōjōbō is the king of the Tengu. Sōjōbō is closely linked to famed warrior Minamoto no Yoshitsune 源義経 (1159-1189), one of Japan's most revered samurai. In a well-known legend, Yoshitsune lived among the tengu in his youth and received training in the arts of war from Sōjōbō himself.

- Tengu Saburō 天狗三郎 of Mt. Iizuna 飯綱山 in Nagano Prefecture. Also known as Izuna Gongen 飯網権現, Izuna Saburō, Mishima Daimyōgi, Izuna Myōjin, Daitengu Saburō, Izuna-Atago, Akiba Gongen, Sanshakubō Gongen, Akiba Daitengu. The Izuna cult is first mentioned in the Kamakura-era text Asabashō 阿婆縛抄 (1279) and associated with Togakushi Temple 戸隠神社 in Nagano prefecture. Izuna Gongen is also enshrined at Yakuōin Temple 薬王院 on Mt. Takao 高尾山 (in Hachiōji, Tokyo). Typically depicted in artwork as a Tengu riding atop a white fox. http://www.aisf.or.jp/~jaanus/deta/i/izusangongen.htm. Also see Kokugakuin http://eos.kokugakuin.ac.jp/modules/xwords/entry.php?entryID=193 Iizuna Saburō Tengu 飯綱三郎天狗, Izusan Gongen 伊豆山権現, Hashiriyu Gongen 走湯権現, Izuna Myōjin

Izuna Saburō Tengu 飯綱三郎天狗 (aka Daimyō Tengu Izuna Saburō 大妙天狗飯綱三郎, Izunasan Gongen 伊豆山権現, or Hashiriyu Gongen 走湯権現) is the guardian deity of sacred Mt. Izusan 伊豆山 (a Shugendō site from around the Kamakura period) said to reside at a hot spring on Izusan in Shizuoka prefecture. Over time the deity was linked with Hakone Gongen 箱根権現 and Kōrai Gongen 高麗権現 -- the three are considered one and the same. In the Meiji period, when Buddhism and Shintōism were forcibly separated by the government, Izusan became a holy Shintō site and many of its Buddhist treasures were lost or scattered. Izusan Gongen is the Shintō manifestation of the Buddhist deity Senju Kannon 千手観音 (1000-armed Kannon). http://www.aisf.or.jp/~jaanus/deta/i/izusangongen.htm

PHOTO http://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%A4%A9%E7%8B%97

http://eos.kokugakuin.ac.jp/modules/xwords/entry.php?entryID=193

Based on this entry, the cult is believed to have first spread among ascetic practitioners (shugen) at Togakushi. Later, however, the cult became increasingly independent in the form of Izuna shugen, and in the Muromachi period it was led by a famous pilgrim guide (sendatsu) named Sennichi Tayū.

Iconographically, Izuna Gongen is usually depicted in the form of a tengu [a mythical winged demon with long nose believed to live deep in the mountains], and riding upon a white fox, a depiction resembling that of the deity Akiba Gongen [Sanshaku Gongen]. Sanjakubō (三尺坊?) of Mount Akiba Since Akiba Gongen is also believed to have originated in the Mt. Izuna and Togakushi area, the two deities are obviously closely related. Since the Buddhist counterpart (honji or "original essence"; see honji suijaku) of Izuna Gongen is said to be the bodhisattva Jizō (Sk. Ksitigarbha), the cult displays a mutual influence with the Atago cult (which involved an amalgamation with Shōgun Jizō or "Jizō of victory"). As a result, the deities are often referred to by the conjoined name Izuna-Atago.

The Izuna cult also underwent combination from an early period with the cult of the Buddhist deity Dakini (Sk. Dakini), and a kind of magical technique was adopted from the medieval period involving the use of foxes as spirit familiars. This belief spread even among members of the court and warriors; the deputy shogun Hosokawa Masamoto (1466-1507) was known to have practiced the Izuna-Atago techniques (ref., Ashikaga kiseiki, Jūhen Ōninki), and the imperial regent Kujō Tanemichi (1509-1097) is likewise said to have studied Izuna practices (ref., Matsunaga Teitoku, Taionki). Such practices involving on the control of spirit familiars of foxes (kitsune tsukai) later came to be called izuna tsukai.

The Izuna cult came to be associated with military arts as well, and Takeda Shingen and Uesugi Kenshin are known to have shown strong devotion to Izuna Gongen as a martial tutelary. The school of Japanese fencing called Shintō Munenryū is also said to have originated at Mt. Izuna. In addition to Mt. Izuna in Nagano, Izuna Gongen can be found enshrined at Yakuōin on Mt. Takao (in Hachiōji, Tokyo), Hinagadake in Gifu, and Mt. Izuna in Sendai. The Izuna Gongen of Sendai goes by the name Izuna Saburō, and is particularly well known as one of the "three tengū of Japan." Some scholars have suggested that belief in this tengu was responsible for the Izuna cult. b.Daimyogi: person of great rank and privilege, Daimyo (大名 ?), and of exceptional and exquisite wisdom and skill/technique.

Izusan Gongen 伊豆山権現

Also called Hashiriyu Gongen 走湯権現. A deity associated with a hot spring which wells up on Izusan 伊豆山, a hill of 166m in Shizuoka prefecture close to the sea coast. A shrine was raised to the deity in the early 9c. In the late Heian period an esoteric Buddhist mikkyou 密教 temple called Hannya-in 般若院 was built on Izusan. The sculpture of Izusan Gongen that was the principal image of Hannya-in survives. He originally held a mace shaku 笏 and a halberd houbou 宝鉾. He wears a court hat, court robes, and kesa 袈裟 (Buddhist robes). This combination expresses particularly well the unity of Buddhism and Shinto shinbutsu shuugou 神仏習合. In the Kamakura period, Izusan became a mountain used for ascetic practice shugendou 修験道 (see *En no Gyouja 役の行者), and was linked with Hakone 箱根 as a pilgrimage destination, recieving government patronage. Izusan remained well known as a shugendou sacred mountain until the early Meiji period, when the site was made Shinto and the Buddhist objects scattered. A Buddhist manifestation *honjibutsu 本地仏 of Izusan Gongen is the One-thousand Armed Kannon *Senju Kannon 千手観音.

Some Other Tengu Some Other Tengu

- Buzenbō 豊前坊, the king of the tengu on Mount Hiko 英彦山 in Kyūshū.

- Saganbō or Sagamibō 相模坊; also known as Saganbō Daigongen 相模坊大権現; the tengu of Mt. Shiromine 白峯山 in Sanuki 讃岐 (present-day Kagawa prefecture).

- Akiba Daigongon Tengu Akihabara, Akibasan Sanshakubō 秋葉山三尺坊, Akiba Gongen, Sanshaku Gongen, Sanjakubō

http://tokyotrad.blogspot.com/2010_01_01_archive.html Also

In 17th century, Tokugawa Ieyasu was appointed to SHOGUN. And he brought Akiba Daigongen shrine from his hometown to here. People called this place Akihabara since this event. Akiba Daigongen is one of god. Akiba Daigongen looks Tengu like black crows. And he rides on fox. He is in charge of fire prevention. In Edo period in Japan, the fire often brought tragedy, because traditionally wooden buildings are many. So, Shogun brought Akiba Daigongen from his hometown. From that reason, Akiba daigongen was believed by successive Shogun. In Edo period, many drugstores gathered.

Great Tengu Stuff and Dakini Stuff White Fox Stuff

http://www.zoeji.com/02charms/02-chinpou/02char-chinpou.html

天狗覚書(承前) - [ Translate this page ]

すると稲荷=狐=仏教の鬼神たる荼吉尼天=飯縄権現=飯縄三郎=天狗

と展開する事が可能となる。 ..... といふいわれあり、むかしは人にてさふらひしが、

仏法を能習ひ我より他に智者なしと大まんじんをおこすゆへ、仏にはならずして天狗道へおつるなり」

www.geocities.jp/edelfalter/recture/tengu2.htm - Cached

Sometime in the Muromachi period (1392-1568), for reasons unknown, two warrior-like TENGU goblins begin appearing in Dakini artwork, one named Tonyūgyō 頓遊行 holding a spear (or other weapon) and appearing at the bottom-right of the central deity, and another named Suyochisō 須臾馳走神, winged and red-colored, appearing at the bottom-left. These goblins appear, for example, in the Dakiniten Mandalas discussed above. Tengu are considered to be manifestations (Jp. = Keshin 化身) of Shintō deities known as Yama-no-kami 山の神 (mountain guardians often associated with tall trees). ADD THE BRET STUFF ON IZUNA SABURO.

Tonyūgyō Tengu 頓遊行神 Tonyūgyō Tengu 頓遊行神

Suyochisō Tengu 須臾馳走神

Two Tengu appear at the bottom of the scroll (the white-colored Tonyūgyō 頓遊行 and the red-colored Suyochisō 須臾馳走; their names suggest “swiftness,” and thus they appear animated). The two are considered Dakini’s attendants, as well as martial deities who serve Inari Daimyōjin 稲荷大明神 at Japan’s first and oldest Inari shrine (in Kyoto) known as Fushimi Inari Taisha 伏見稲荷大社.

Inari Daimyōjin 稲荷大明神 伏見稲荷大社 Fushimi Inari Taisha (in Fushimi-ku, Kyoto)

http://www.lares.dti.ne.jp/~hisadome/shinto-shu/

http://www.lares.dti.ne.jp/~hisadome/shinto-shu/files/14.html

稲荷明神には二人の式神が仕えている。

頓遊行神と須臾馳走神である。

稲荷大明神の本地は大聖文殊師利菩薩である。

垂迹は陀枳尼明王で等流の化身である。また、濁悪の教主である。

In addition to the two TENGU shown in the above photos, another TENGU depicted atop a white fox (and thus probably linked to Dakiniten-Benzaiten) is Dōryō Daigongen 道了大権現. Dōryō was a mountain ascetic before becoming a Soto Zen monk. He was eventually appointed as head cook and administrator at Daiyūzan Temple 大雄山 (Kanagawa Prefecture). After his death in 1411 AD, legend says he metamorphosed into a TENGU goblin and became the monastery guardian. According to scholar Duncan Williams in The Other Side of Zen: A Social History of Soto Zen Buddhism in Tokugawa Japan (published 2005, ISBN 0-691-11928-7): “[Upon his death] his body was engulfed in flames as he appeared transformed and stood on a white fox to promise a life free from illness and full of riches for those who sincerely worshipped him.” In addition to the two TENGU shown in the above photos, another TENGU depicted atop a white fox (and thus probably linked to Dakiniten-Benzaiten) is Dōryō Daigongen 道了大権現. Dōryō was a mountain ascetic before becoming a Soto Zen monk. He was eventually appointed as head cook and administrator at Daiyūzan Temple 大雄山 (Kanagawa Prefecture). After his death in 1411 AD, legend says he metamorphosed into a TENGU goblin and became the monastery guardian. According to scholar Duncan Williams in The Other Side of Zen: A Social History of Soto Zen Buddhism in Tokugawa Japan (published 2005, ISBN 0-691-11928-7): “[Upon his death] his body was engulfed in flames as he appeared transformed and stood on a white fox to promise a life free from illness and full of riches for those who sincerely worshipped him.”

SPECULATION. The “food chain” may be the common connection between Dakiniten-Benzaiten and the Tengu. Consider the folllowing Zen story: “One day a hunter was in the mountains when he happened to see a snake killing a bird. Suddenly a boar appeared and began to devour the snake. The hunter thought he should kill the boar, but changed his mind because he did not want to be a link in such a chain, and cause his own death by the next predator to come along. On his way home he heard a voice call to him from the top of a tree. It was the voice of a Tengu. It told him how lucky he was, for had he killed the boar, the tengu would have killed him. The man subsequently moved into a cave and never killed another animal.” <Sources: A Field Guide to Demons, Fairies, Fallen Angels, and Other Subversive Spirits (by Carol Mack, Dinah Mack) and Animal Motifs in Asian Art: An Illustrated Guide to Their Meanings and Aesthetics (by Katherine M. Ball).> See Konjyaku Monogatari.

SOURCES

- Tengu Zoshi and Its Critique of Late Kamakura Buddhism

By Haruko Wakabayashi, Princeton University. Very interestly scholarly paper on the role of the Tengu in Buddhist mythology in the late Kamakura Period. Click above link to read this paper (this will open a pop-up window).

- Charles C. Goodin's Tengu Lore Page

Charles C. Goodin is an instructor at the Aiea Matsubayashi Karate Dojo in Aiea, Hawaii. He is an attorney, writer, and the publisher of the Yoshitoshi Ukiyo-e Web Gallery and the Kuniyoshi Ukiyo-e Web Gallery.

- www.thetengu.com/tengu.

Interesting site with photos, stories, and chat board. Of special note are the many examples they give of Tengu-like crow-like creatures found in other countries.

- www.travellady.com

Mount Kurama Village and Temple. Home of the Legendary Tengu King, Sojobo.

- Osugi Musical Theatre - Tengu Art Project

Osugi Musical Theatre is a community theatre group based in Komatsu, Ishikawa, Japan. The group performs original musicals at home and abroad. They are also running a Tengu costume design contest (deadline June 1, 2007). Their upcoming fall 2007 show is entitled "Yokubari Tengu III: Adventures on the Tengu Planet."

- The Tengu by M. W. de Visser, courtesy of Google Books.

Other Tengu Terminology & Trivia

- Daitengu, or ”Major Tengu.“ Typically appears as man with a very long nose and red face. They often wear a pair of geta (Japanese wooden sandals), and carry a magic fan made of bird feathers that can create a hellish tornade.

- Kurama Tengu, or ”Tengu of Mt.Kurama“

- Karasu Tengu, ”Kotengu” or ”Minor Tengu.'' They serve the Daitengu. Another common type of tengu. A Karasu Tengu is rather small, with the head and wings of a black crow. Some say that Tengu don't want human society to become stable and powerful, so they intervene to provoke war and civil disorder.

Last Update: Sept. 2013

Added work notes that still require editing.

|

|