|

KOREAN KANHWA SŎN BUDDHISM -- SPECIAL REPORT

|

|

Top Menu

Intro Page Intro Page

|

Architecture

25 Photos

|

Creatures

42 Photos

|

Deities

59 Photos

|

Doors

13 Photos

|

Paintings

60 Photos

|

People

32 Photos

|

Votive Icons

21 Photos

|

|

Also See

|

Korean Influence on Early Japanese Buddhism. Not a systematic study, but rather a "sketch" of the key contributions of Korean monks, artisans, and specialists to early Japanese Buddhist doctrine, art, and architecture. 30 Photos.

|

|

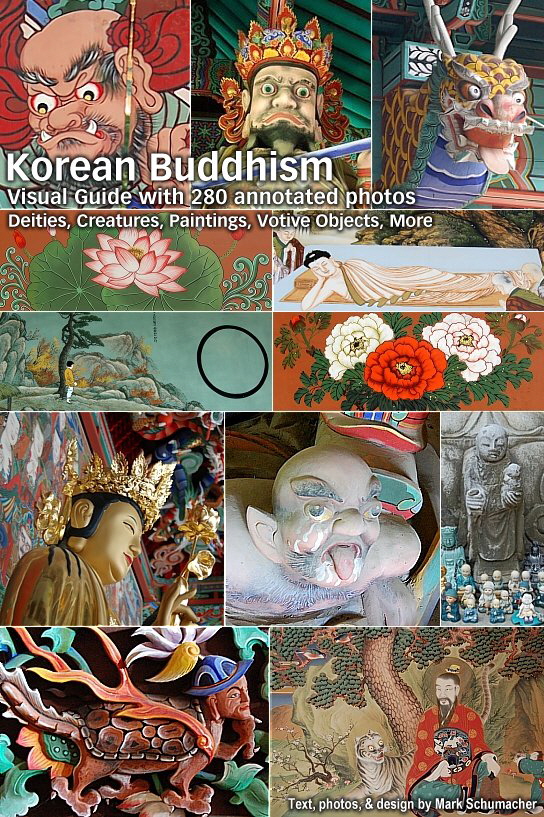

TOP MENU & INTRODUCTION. 280+ PHOTOS. These pages and photo galleries are devoted to Korean Buddhism. They are aimed at students, teachers, art historians, and scholars of East Asian Buddhism (China, Korea, Japan). They are meant to highlight the "commonality" among the three nations. The photos were taken during a recent trip (June-July 2012) by site author Mark Schumacher, who journeyed to Korea to explore Kanhwa Sŏn 看話禪 and Hwadu 話頭 meditative techniques, the Korean counterpart of Chinese gōngàn practice (aka Japanese Zen kōan meditation). These terms and related concepts are discussed below. The Kanhwa conference, retreat, and tour took place between June 23 and July 3, 2012. It was organized by the Institute for the Study of the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism and by the International Seon Center (both located at Donnguk University, Seoul). The Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism is the predominant order of meditation in South Korea. Participants included advanced graduate students, professors, and independent scholars in Korean Religions and Buddhist Studies. Over 280 photos are presented herein, with detailed annotations appearing below the slideshow window. All photos and annotations by Schumacher unless otherwise stated. FACEBOOK. For Kanhwa participants with Facebook accounts, please post your photos, thoughts, and critiques at the Korea Kanhwa Sŏn Facebook Group Page, an unofficial non-affiliated forum for event participants to share their experiences. It is an "unrefereed" forum where anything goes. Participants like Jacqueline Jingjing and Lin Peiying have also created their own individual photo galleries on Facebook. To view or post to them, please visit: Jacqueline's Facebook || Peiying's Facebook || Mark's Group Facebook TOP MENU & INTRODUCTION. 280+ PHOTOS. These pages and photo galleries are devoted to Korean Buddhism. They are aimed at students, teachers, art historians, and scholars of East Asian Buddhism (China, Korea, Japan). They are meant to highlight the "commonality" among the three nations. The photos were taken during a recent trip (June-July 2012) by site author Mark Schumacher, who journeyed to Korea to explore Kanhwa Sŏn 看話禪 and Hwadu 話頭 meditative techniques, the Korean counterpart of Chinese gōngàn practice (aka Japanese Zen kōan meditation). These terms and related concepts are discussed below. The Kanhwa conference, retreat, and tour took place between June 23 and July 3, 2012. It was organized by the Institute for the Study of the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism and by the International Seon Center (both located at Donnguk University, Seoul). The Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism is the predominant order of meditation in South Korea. Participants included advanced graduate students, professors, and independent scholars in Korean Religions and Buddhist Studies. Over 280 photos are presented herein, with detailed annotations appearing below the slideshow window. All photos and annotations by Schumacher unless otherwise stated. FACEBOOK. For Kanhwa participants with Facebook accounts, please post your photos, thoughts, and critiques at the Korea Kanhwa Sŏn Facebook Group Page, an unofficial non-affiliated forum for event participants to share their experiences. It is an "unrefereed" forum where anything goes. Participants like Jacqueline Jingjing and Lin Peiying have also created their own individual photo galleries on Facebook. To view or post to them, please visit: Jacqueline's Facebook || Peiying's Facebook || Mark's Group Facebook

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

KANHWA SŎN CONCEPTS & KEYWORDS

|

-

|

|

Bodhidharma statue at the Asian Art Museum, Seoul. Enlarge photo.

Wall-gazing Bodhidharma. Modern painting adorning outer wall at Seokjongsa Temple (South Korea)

See full photo.

Bodhidharma (Daruma) 達磨図

Japanese painting, by Hakuin Ekaku 白隠慧鶴 (1685-1768). H 122.0 cm

x W 58.2. Tokeii Temple 東慶寺, Kamakura, Japan

|

|

Sŏn or Seon 선. Korean spellings for the Chinese word Chán 禅 (J = Zen). Sŏn/Seon means "meditation" and refers to the meditation practices and teachings that arose from the Chinese Chán tradition, whose patriarch is Bodhidharma (C = Dámó 達磨, K = Talma 달마, J = Daruma 達磨). Bodhidharma was an Indian sage who lived sometime in the fifth or sixth century CE. He is considered the founder of Chán Buddhism and credited with Chán's introduction to China. Bodhidharma's philosophy developed first in China. It then rose to prominence in Korea around the ninth century (see Korea's Nine Mountain Schools of Seon below) and began to bloom in Japan during the Kamakura period (1185-1333). In Korea it is called Sŏn/Seon, while in Japan it is called Zen. Says Mario Poceski (University of Florida): "Among the key features that came to characterize Chan (Sŏn/Zen) 禪 Buddhism in Song China (960-1279), a period during which the Chan school consolidated its position as the main tradition of elite Buddhism, was the development of distinctive paradigms of contemplative praxis, especially the kànhuà 看話 ("observing the critical phrase") technique of Chan meditation. This distinctive type of meditation practice -- whose emergence was closely related to the creation of unique types of Chan literature, especially the various gōngàn 公案 ("public case") collections -- was originally popularized by major Chan figures such as Dàhuì Zōnggǎo 大慧宗杲 (1089–1163). Before long, Kànhuà Chán or Kanhwa Sŏn 看話禪 was also introduced to Koryŏ Korea 高麗 (918-1392) through the efforts of eminent Korean monks such as Pojo Chinul 普照智 (1158-1210; K = 보조지눌), and to this day it remains one of the central elements of Korean Buddhism. (Note -- similar techniques were introduced into Kamakura Japan (1185-1333), where it became especially identified with the Rinzai 臨濟 sect.) Ever since, this kind of contemplative practice, along with other variations on similar themes, have exerted pervasive impact on Buddhism in Korea (and other parts of East Asia) as a major method of spiritual cultivation." <source: Development of Chan (Sŏn) Approaches to Meditative Praxis during the Tang Era, by Mario Poceski, pp. 62-81, in Volume Two of "Ganhwa Seon in the History of Buddhist Thought, The 3rd International Conference on Ganhwa Seon," held on June 23-24, 2012, at Dongguk University, Seoul, Korea.

- Kanhwa Sŏn or Ganhwa Seon 간화선 (C = Kànhuà Chán 看話禪, J = Kanna Zen or Kanwa Zen). Literally "phrase-observing meditation." Says the Digital Dictionary of Buddhism (sign in with user name = guest): "Gongan (J. kōan) contemplation; a Chan/Seon/Zen meditation method that seeks direct attainment of enlightenment through investigation of the 'keyword' (Ch. huàtóu; K. hwadu, 話頭). This Chan approach was first popularized by the Chinese Linji 臨濟 monk Dahui 大慧, who taught this method to be superior to the competing Caódòng 曹洞 approach to meditation, known as 'silent illumination meditation' 默照禪. Throughout the subsequent history of East Asian Buddhism, phrase-observing meditation would be associated with Linji/Imje/Rinzai, while silent illumination became the main method of Caodong/Sōtō. 看 means 'to see' and 話 means a question. Here 'seeing,' means for the practitioner to probe deeply into the doubts in his own mind, as the key word points to the place where thoughts arise. In Korean Seon it is often applied as a synonym for gong-an 公案, but precisely speaking, the two are different. While gong-an refers to an entire exchange, usually a dialogue between Master and student, hwadu refers to the core issue. Originally in China gong-an meant a precedent in a public case, while in Chan/Seon/Zen training it refers to a realized teaching pointing to the nature of ultimate reality. The gong-an is characterized as a conundrum which cannot be solved by discursive understanding, yet with diligent practice it makes clear the limitations of thought and eventually forces the student to go beyond logical contradictions and dualistic modes of thought. Hwadu is the word or expression into which a gong-an resolves itself through struggle with it as a means of spiritual training. For instance, in the very famous gong-an 'Zhaozhou's Dog,' 趙州狗子 the word mu ( 'no,' 'is not' 無) is the hwadu. In hwadu practice the practitioner is understood to be directly apprehending his original nature 本性 (or buddha-nature 佛性). This is why it is referred to as 'seeing original nature and accomplishing Buddhahood' 見性成佛. The method is seen as a means of access to sudden enlightenment which is revealed at the moment the practitioner breaks open his or her hwadu, thus 'leaping over thousands of teachings of Buddha and successive Chan masters.' The ganhwa approach has been popular in China and Korea, and in recent times is gaining popularity in Western countries. [O.B. Chun]" <end quote>

- Hwadu 화두 (C = Huàtóu 話頭, J = Watō). Literally "key phrase, principal theme." Says the Digital Dictionary of Buddhism (sign in with user name = guest): The 'critical phrase,' 'principal theme,' of the larger gōngàn/gong-an/kōan exchange. The classic example is the longer gōngàn. "A monk asked Zhaozhou 趙州, 'Does a dog have buddha-nature 佛性, or not?' Zhaozhou answered, 'It doesn't have it (wu/mu/mu 無)' " (more commonly translated as 'no' ). 〔無門關 T 2005.48.292c23〕 The gong'an is the whole exchange, the huatou/watō/hwadu is the word wu/mu/mu. The hwadu is the focus of a sustained investigation, via a more discursive examination of the question, "Why did Zhaozhou say a dog doesn't have the buddha-nature when the answer clearly should be that it does?," which is called 'investigation of the meaning;' this investigation helps to generate questioning or 'doubt,' which is the force that drives this type of practice forward. As that investigation matures, it changes into a nondiscursive attention to just the word 'no' itself, which is called 'investigation of the word' 看話 (K. ganhwa) because the meditator's attention is then thoroughly absorbed in this ' sensation of doubt.' This type of investigation is said to be nonconceptual and places the meditation at the 'access to realization,' viz. 'sudden awakening.' The most sustained treatment of the use of hwadu in Chan/Zen/Seon meditation appears in the Korean tradition and 'Keyword Meditation' (ganhwa Seon 看話禪) remains the principal type of meditation practiced in contemporary Korean Buddhism. There is extensive discussion of the Korean monk Jinul's (知訥 1158-1210) treatment of ganhwa Seon in R. Buswell, Tracing Back the Radiance; Jinul's extensive treatise "Resolving Doubts about Observing the Hwadu," appears in the earlier unabridged version of that book, The Korean Approach to Zen: The Collected Works of Chinul. Buswell has also published a chapter on the contemporary practice of ganhwa Seon in The Zen Monastic Experience. Note that 'keywords' are to be distinguished from the 'capping phrases' or 'annotations' (J. jakugo, C. zhuoyu/zhuyu, K. chag-eo 著語). These capping phrases abound in several early Chinese gong'an collections, but after the time of Daitō Kokushi (Shūhō Myōchō; 1282-1337 宗峯妙超) they become especially emblematic of the Japanese Rinzai Zen school's approach to kōan training. 'Capping phrases' are brief phrases, often taken from Chinese literature, which are intended to offer an 'annotation' or 'comment' to a specific Zen or kōan, either to express one's own enlightened understanding or to catalyze insight in another; they are not the 'keyword' of that kōan. The Korean tradition doesn't seem to have ever used 'capping phrases.' See also 公案 and 看話禪.

- Gong-an 공안 (C = Gōngàn 公案, J = Kōan). Literally "public notice," but appropriated as a Buddhist meditation device. Says the Digital Dictionary of Buddhism (sign in with user name = guest): "A public notice, issued by, or dealt with by a Chinese government office. The term was appropriated by Chinese Chan 禪宗 Buddhism, where it was used to refer to a specific Buddhist meditation device, distinguished from the traditional Indian Buddhist forms of meditation such as śamatha/vipaśyanā 止觀. Gong'an meditation (in the West, more commonly known by the name of its Japanese rendering, kōan) usually consists of the presentation of a problem drawn from classical texts, or from teaching records and hagiographies of Tang and Song period Chinese Chan masters. After the case is presented, a question is asked regarding a key phrase (話頭) in the story, which usually presents a position that contradicts accepted Buddhist doctrinal positions or everyday logic. Its purpose is not to elicit a rational answer, but to serve as a focal point for a dynamic form of contemplation, which results in a nondualistic experience. After being developed in China, this practice spread to Korea as gong-an, where it has remained a prominent form of meditation in Korean Seon schools (mainly Jogye 曹溪宗) down to the present. In Japan, kōan meditation has been practiced mainly by the Rinzai school 臨濟宗, although certain Sōtō 曹洞宗 teachers like Dōgen 道元 did acknowledge the practice. Gongans are contained in edited collections, two of the most popular of which are the Wumen guan 無門關 and the Biyan lu 碧巖錄. For a volume study of the historical background of gong'an in China and Japan see Heine and Wright The Kōan: Texts and Contexts in Zen Buddhism (Oxford UP, 2000). [cmuller]

- Jogye or Chogye 조계종 (C = 曹溪宗 Caóxī zōng, J = Sōkei shū). The Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism 대한불교조계종 (C = 大韓佛敎曹溪宗) is the predominant school of Korean Buddhism. It stresses meditation and sudden enlightenment, but also includes scriptural study. It traces it origins back to Bodhidharma, an Indian sage who lived sometime in the fifth or sixth century AD and is considered the founder of Chán Buddhism 禅. See details above under Sŏn or Seon.

|

|

Temples, Retreat, Dharma Talks, Key Players Temples listed in order of visitation

|

-

|

|

Maste Subul, Magoksa Temple

Meditation Hall, Magoksa Temple

|

|

Magoksa Temple (K = 마곡사, C = 麻谷寺). Official Homepage || Review by KoreaTemple.net. Magoksa is the head temple of the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism, located just a few hours south of Seoul by bus/car. It is here that our group held its meditation retreat between June 23 and July 1. Master Subul, the head of the International Seon Center at Dongguk University and abbot of Beomeosa Temple, instructed our group throughout with talks and Q&A sessions. Subul believes Kanhwa Sŏn to be the most revolutionary spiritual practice in the history of mankind. It can be, he says, "made readily accessible to the public and should be. Now is the time to introduce to the world, not only Korea, the effectiveness of Kanhwa Sŏn practice. History has given a mission to us who live in this age of open information; that is to make Kanhwa Sŏn accessible to all." <source: keynote address at the 3rd Int'l Conference on Ganhwa Seon, July 23, 2012> Subul believes that "sudden awakening" is possible (some members in our group apparently achieved awakening during the retreat, but I saw no physical or spiritual changes in them). Subul also says: "Once one is awakened, there is no more backsliding." When asked about the role of Buddhist deities and the many icons enshrined at Kanhwa Sŏn temples, he replied: "They are dead skeletons in the street, yet important stepping stones for many. Once the practitioner reaches a certain level, however, they are a hindrance. There is an old Buddhist story that goes 'If you meet the Buddha on the road, kill him.' <end quote> What does this mean? It means that Buddha is you, not someone you meet on the road. Your conception is wrong. Get rid of it. Kill all images and illusions and keep practicing. This story is attributed to Chinese master Línjì Yìxuán 臨濟義玄 (d. 866-7), the founder of the Línjì school of Chan Buddhism (K = Imje 임제, J = Rinzai 臨濟). It's meaning is akin to the well-known Taoist phrase: "The Tao that can be named is not the eternal Tao."

-

|

|

Some Donghaksa bikuni (nuns)

|

|

Donghaksa Temple (K = 동학사, C = 東鶴寺)

See KoreaTemple.net. || See Buddhist-tourism.com. Largest center of study for female monks (bikuni) in Korea, Donghaksa specializes in Buddhist studies and is part of the Jogye order. A large contingent of Donghaksa nuns joined us on the retreat and temple tour. They were, to many, one of the highlights of the entire event. Their friendliness, inquisitiveness, and heartfelt search for inner awakening brought a palpable "spiritual" element to the event -- one that would have been missed if only monks attended.

- Gapsa Temple (K = 갑사). Gapsa Homepage || Review by Koreatemple.net

-

|

|

Master Jeokmyeong, Bongamsa Temple

Master Muyeo, Chukseosa Temple

|

|

Bongamsa Temple. 鳳巖寺. One of the Nine Mountain Schools (禪門九山) of Seon practice in Korea. Here we heard a Dharma talk from Master Jeokmyeong. This temple, says Visitkorea.or.kr, is "open to the public only one day per year. Visit on any day other than Buddha's Birthday and you will be turned away at the gate. A major Korean center for the practice of Seon (better known in the West by its Japanese name of Zen). Bongamsa is one of Korea's oldest centers of Seon meditation. This Seon tradition continues to this day. In 1982, the temple and the surrounding mountain and forests were closed off to the outside world to produce a better meditation environment. Not surprisingly, there's a good deal of competition between monks to enter the monastery, where monks, from the abbot on down, meditate for at least eight hours a day." <end quote>

- Chukseosa Temple 鷲棲寺. Here we heard a Dharma talk from Master Muyeo 無如. Temple review by Bonghaw.go.kr || Temple review at KBS.co.kr || About temple's Yakushi icon.

-

|

|

Master Hyeguk, Seokjongsa Temple

Huìkě 慧可 cutting off arm. Japan, 1498. By Sesshū 雪舟 (1420-1506). Sainenji Temple 斎年寺, Aichi Pref. Photo from Kyoto National Museum

|

|

Seokjongsa Temple (see review at ChungbukNadri.net). At this temple we heard a Dharma talk from Master Hyeguk. At 22 years of age, before joining the order, Hyeguk burnt off one of his fingers to demonstrate to his father (who was against Hyeguk becoming a monk) his determination to join the Buddhist order. In subsequent decades, Hyeguk burnt off two more fingers on his right hand as a vow to achieve awakening in this life. Hyeguk's sacrafice calls to mind the famous Chinese legend of monk Huìkě 慧可 (K = Hyega 혜가, Jp. = Eka) who cut off his elbow. This story comes in various versions. In the Annals of the Transmission of the Dharma Treasure (Chuán fǎbǎojì 傳法寶記; Jp. = Denpō Hōki 伝法宝記), an early 8th-century Chinese text attributed to Dharma-master Dù Fěi 杜朏 (Jp. = Tohi), we are told that Huìkě travels to Shaolin Temple 少林寺 (Jp. = Shōrinji ) in modern-day Henan Province (China) to ask Bodhidharma to teach him zazen 坐禅 (sitting meditation). But when he arrives, he finds Bodhidharma immersed in a meditation technique called "wall-gazing" 壁観 (Chn. = Bìguān, Jp. = Hekikan) or "wall facing" (Chn. = Miànbì, Jp. = Menpeki 面壁). Huìkě waits patiently in the snow for a long time (in some versions, for one week), until Bodhidharma informs him that Chan (Seon/Zen) study requires discipline and hardship. Huìkě subsequently cuts off his arm and presents it to Bodhidharma as a sign of his sincerity and determination, as a sign of his willingness to undergo any sacrifice for the privilege of being Bodhidharma's pupil. Huìkě eventually became Daruma's successor and China's second Chan patriarch. For more details and images, click here. Master Hyeguk cut our Dharma talk short by saying "Since you don't have any heartfelt questions, we can end this session." He was referring to the fact that most questions by the group were of an academic nature.

- OTHER KEY PLAYERS

|

|

|

|

|

- Venerable Jongho, the main man behind organizing the entire event. He is a professor at Dongguk University and Director of the Institute for the Study of the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism.

- Robert Buswell, Professor of Buddhist Studies, UCLA. Another of the event's main organizers. A former Jogye monk; now one of the most eminent scholars of Korean Kanhwa Sŏn.

- Haemin, our interpreter. Haemin is an assistant professor of East Asian Religions at Hampshire College, where he is known as Professor Ryan BongSeok Joo. He is also a best-selling author in Korea. Got his B.A. in Religious Studies at the University of California, Berkeley, his M.T.S. in the History of Religion from Harvard University Divinity School, and his M.A. and Ph.D. from Princeton University.

- Kim Young Soo (administrator at the Dongguk International Seon Center). He served as our main tour guide.

|

|

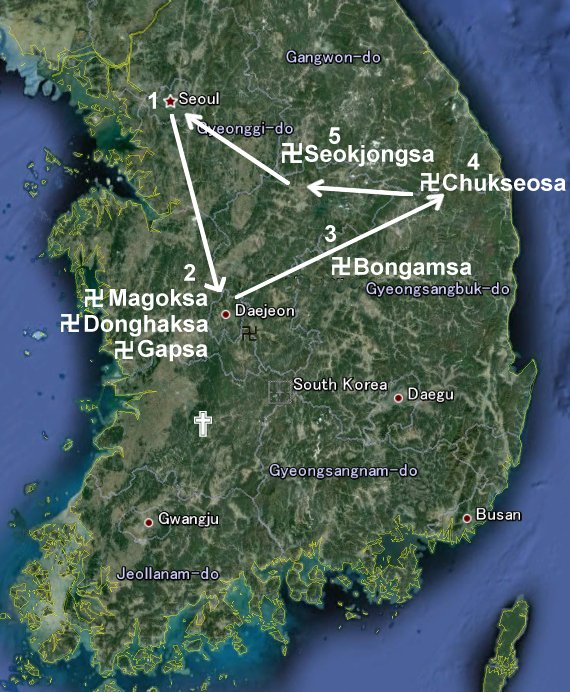

Location of temples we visited in South Korea.

Other Temple Resources

|

|

Nine Mountain Schools of Seon (Sŏn) Practice in Korea 禪門九山

|

|

Nine Mountain Schools 禪門九山 (C = Chánmén Jiǔshān, K = Seonmun Gusan 선문구산, J = Zenmon Kyūsan). An appellation for the early schools of Korean Seon (Sŏn) practice. Each school was connected with one of nine mountain monasteries. The nine are listed below.

- Gaji-san school (迦智山), established at Borimsa (寶林寺) under the influence of Doui (道義; d. 825) and his grand-student Chejing (體澄; 804–890). Doui studied in China under Zhizang (智藏; 735–814) and Baizhang (百丈; 749–814).

- Seongju san (聖住山) school, established by Muyeom (無染; 800–888) who received his inga 印可 from Magu Baoche (麻谷寶徹; b. 720?).

- Silsang san (實相山) school, founded by Hongcheok (洪陟; fl. 830), who also studied under Zhizang.

- Huiyang san (曦陽山) school, founded by Beomnang and Jiseon Doheon (智詵道憲; 824–882), who was taught by a Korean teacher of the Mazu transmission.

- Bongnim san (鳳林山) school, established by Wongam Hyeon'uk (圓鑑玄昱; 787–869) and his student Simhui (審希, fl. 9c). Hyeon'uk was a student of Zhangjing Huaihui (章敬懷暉; 748–835).

- Dongni san (桐裡山) school, established by Hyecheol (慧徹; 785–861) who was a student of Jizang.

- Sagul san (闍崛山) school, established by Beom'il (梵日; 810–889), who studied in China with Yanguan Qian (鹽官齊安; 750?-842) and Yueshan Weiyan (樂山惟嚴).

- Saja san (獅子山) school, established by Doyun (道允; 797–868), who studied under Nanjuan puyuan (南泉普願; 748–835).

- Sumi-san school (須彌山) founded by Leom (利嚴; 869–936), which had developed from the Caotong 曹洞 lineage. The term Gusan in Korea also becomes a general rubric for "all the Seon schools," holding such connotations down to the present.

Source: Digital Dictionary of Buddhism (DDB) (sign in with user name = guest)

The DDB includes much more information about the nine. A visit is highly recommended.

|

|

LEARN MORE

|

|

English Resources

- Buswell, Robert E., Jr. See The Korean Approach to Zen: The Collected Works of Chinul. Honolulu: University of Hawai`i Press, 1983. Also see his:

- Transmitting the Forms of Divinity: Early Buddhist Art from Korea and Japan. Comparing Korean and Japanese Buddhist art, this volume explores the cultural, ideological and artistic exchange between the two countries during the 6th-9th centuries, when Buddhism took hold throughout northeast Asia. Buddhist sculptures in gilt bronze, wood and stone are the main focus of this work, which contains essays by Korean, Japanese and American scholars.

- Thought and Praxis in Cotemporary Korean Buddhism: A Critical Examination, by Jongmyung Kim, Academy of Korean Studies, South Korea

International Conferences on Kanhwa Sŏn (Ganhwa Seon)

|

|