|

|

|

|

|

|

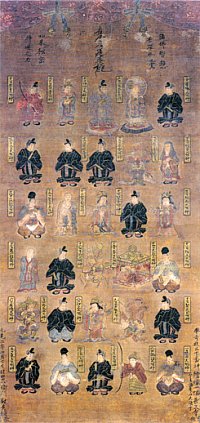

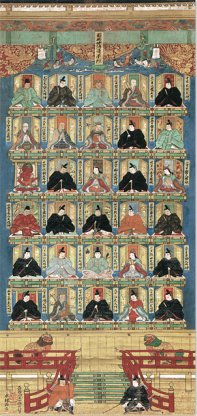

Sanjūsanbanshin 三十番神画像

Color on silk, H 71.4 cm, W 33.8 cm.

Daihōji Temple 大法寺 (Toyama Pref.)

Muromachi Period 室町時代.

Dated 1572. Genki 3 元亀3年.

Photo from Temple's Web Site.

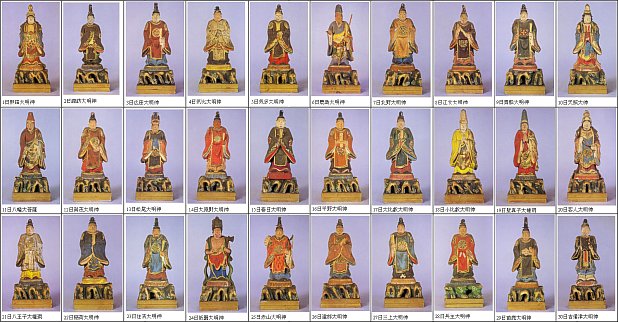

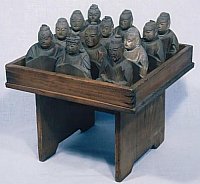

Myōhōji Temple 妙法寺 (Nichiren) in Osaka. Wooden statues of the 30 kami, 10 female rasetsu, and Kariteimo inside the Banjindō 番神堂 (special structure for the 30 kami). The temple holds an annual event on Sept. 15 to venerate this group of deities. Age of statues not listed. Actually, there are now 31 deities to reflect the introduction of the solar calendar and its 31-day month. The new deity is Goban Zenshin 伍番善神.

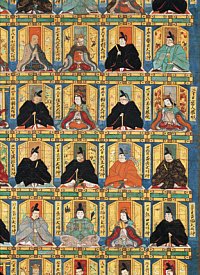

Hanging scroll of Sanjūbanshin

Edo Era ?? (No date given).

Photo from Shinto Museum

of Kokugakuin University

|

|

|

|

|

さんじゅうばんしん or さんじゅうばんじん さんじゅうばんしん or さんじゅうばんじん

SANJŪBANSHIN or SANJŪBANJIN

THIRTY KAMI TUTELARIES OF THE

30 DAYS OF THE MONTH 三十番神

Translated variously as

30 Kami Protecting the Lotus Sutra

30 Kami Protecting the Buddhist Scriptures

30 Kami Guardians of the Imperial Palace

30 Kami Guardians of the Japanese Nation

Related Pages: Secret Buddhist Deities of the

30 Days of the Month (Sanjūnichi Hibutsu 三十日秘仏)

Origin = Japan (with Chinese antecedents)

The origin of this grouping is clouded in uncertainty. By tradition, it is said to have originated with Tendai monk Ennin 円仁 (794-864), who reportedly invited 30 powerful kami (local Japanese deities) to come to Mt. Hiei 比叡 (near Kyoto) to guard a copy of the Lotus Sutra that he himself had made and enshrined at the mountain's temple-shrine multiplex. However, the earliest textual record of the group (details below) dates from the 11th century. In general, these 30 kami are invoked to protect the peace and prosperity of the nation, its rulers, and its people, with each kami presiding over one day of the lunar 30-day month. The 30-kami cult was especially important to the Nichiren sect, who invoked them not only as guardians of the Lotus Sutra but also as protectors against curses, broken oaths, and the spirits of the dead. <source Lucia DolceREFERENCES:

Dolce, Lucia. Hokke Shinto. Kami in the Nichiren Tradition. In: Teeuwen, M. and Rambelli, F., (eds.), Buddhas and Kami in Japan. Honji Suijaku as a Combinatory Paradigm. Curzon Routledge, 2003, page 250. >

The 30 kami can be categorized as "good gods" (zenjin or zenshin 善神), but if neglected, they can just as easily abandon the nation and its people. The list of thirty reads like a Who's Who of Japan's most powerful kami, including Myōjin 明神 (manifest deities) from Japan's most eminent shrines (Myōjin Taisha 名神大社), Gongen 権現 (avatars), Tenjin 天神 (deified humans), and the sun goddess Amaterasu Ōmikami. Each is linked to a Buddhist counterpart (honjibutsu 本地仏). The list thus highlights the great syncretic Buddha-Kami merger of the medieval period known as Honji Suijaku NOTES ON HONJI SUIJAKU. During Japan's Heian era (794 - 1185), the numerous kami (Shinto deities) were recognized as traces or manifestations or incarnations (suijaku) of the Buddhist divinities (honji or honjibutsu), and a great syncretic melding occurred, with shrines and temples sharing both deities and sacred grounds.

The Tendai shrine-temple multiplex on Mt. Hiei is a prime example of the syncretic merging of Buddhist and Shinto deities in Japan. The idea of KAMI as Gohojin (guardian deities of the Buddhist doctrine) was a common element in the Heian period. This Kami-Buddhist syncretism was actually formalized and pursued based on a theory called Honji Suijaku, with the Buddhist deities regarded as the honji (original manifestation) and the Shinto kami as their suijaku (incarnations). Another similar term denoting the association between Buddha and Kami is Shinbutsu Shugo. By the late 12th century, the Mt. Hiei shrine-temple multiplex was a well developed honji suijaku complex, or syncretic merger of both Buddhist and Shinto practices and deities.

Honji Suijaku was originally a Buddhist term used to explain the Buddha's nature as a metaphysical being (honji) and the historical human figure Sakyamuni (suijaku) as the manifest trace. In Japan's early Nara period, the honji were regarded as more important than the suijaku. Gradually they both came to be regarded as one, with neither the honji or suijaku considered more important. By the 9th century, Buddhist temples were constructed alongside Shinto shrines on many sacred mountains, epitomized by the holy Shugendo places throughout the Yoshino mountain range and by the powerful Tendai multiplex on Mt. Hiei. The native Shinto kami (deities) residing on these peaks were considered manifestations of Buddhist divinities, and pilgrimages to these sites were believed to bring double favor from both their Shinto and Buddhist counterparts. Another major center of syncretism was the Kasuga Shrine in Nara. The number of deities proliferated. Despite earlier resistance, syncretism was relatively smooth and marked by religious tolerance.

The Honji Suijaku theory was used for most of Japan's religious history to explain the relationship between the kami (indiginous gods) and imported Buddhist divinities. It was only after the Meiji Period, when the government forceably separated the two camps, that Buddhism and Shintoism were portrayed as two distinct philosophies. 本地垂迹. Table One below presents the most common list of the 30 kami alongside their Buddhist counterparts (but, mind you, the Japanese have developed ten different lists over the centuries).

Extant Japanese artwork of the 30-kami set consists largely of hanging scrolls -- not wooden sculptures -- as their main function during religious ceremonies was to act as protective talismans that were hung at the front of the practice hall. Another common practice was to hang or stamp a paper list of their names (jinmyōchō 神名帳) on the wall. Small shrines called banjindō 番神堂 were erected for their worship (note)REFERENCES:

Says Lucia Dolce (page 250):

"The oldest example of a banjindo, which survives as an important cultural property, is at the Myorenji Temple in Okayama prefecture. It consists of three small shrines, and was built in the Meio period (1492-1501), when also the debate between Kanetomo and the Hokke school took place."

Page 250, Hokke Shinto. Kami in the Nichiren Tradition. In: Teeuwen, M. and Rambelli, F., (eds.), Buddhas and Kami in Japan. Honji Suijaku as a Combinatory Paradigm. Curzon Routledge, 2003, page 250. , which commonly occurring during the ritual copying of the Lotus Sutra. These traditions spread to various locations, but only came to prominence in the Muromachi period (14th and 15th centuries) among adherents of Nichiren Buddhism,

REFERENCES:

Nichiren Shonin (1222 - 1282) was the founder of the Nichiren sect of Japanese Buddhism (also known as the Lotus or Hokke sect). Nichiren was a radical religious reformer who once studied at the powerful Tendai monastery on Mt. Hiei, as did Honen, Shinran, Eisai, and other noted monks of that period. Nichiren vehemently disagreed with the popular Jodo (Pure Land) sects, and proclaimed both old and new Buddhist movements to be false religions. He preached in the streets, hoping to revive the purity of Tendai faith in the Lotus Sutra and blaming existing religious sects for the problems then facing the country. He was arrested and exiled twice by authorities, but in each case was later pardoned. He believed faith in the Lotus Sutra alone would bring liberation, and recitation of the phrase "Hail to the Lotus Sutra" was the sole path to salvation. Today, some 85% of Japan's population claim to be Buddhists, with the largest group (around 25 million people) belonging to the Nichiren sect. The head-temple of the sect is located on Mt. Minobu in Yamanashi prefecture and is known as Kuonji Temple.

Hokke Shinto REFERENCES:

Hokke Shinto. Literally "Lotus Shinto," a syncretic form that sprang from the Nichiren Sect of Buddhism. The Nichiren sect originated in the Kamakura era (1185 to 1332) and preaches that unmitigated faith in the Lotus Sutra is the sole means of liberation and salvation. Hokke (Lotus) Shinto did not appear until the subsequent Muromachi period (1392 to 1568). It includes worship of the Sanjubanshin (30 Tutelary Deities of the Lotus Sutra) and belief that the deities will protect or abandon the nation based on the people's practice (or neglect) of the teachings in the Lotus Sutra. The development of Lotus Shinto was strongly influenced by Yoshida Shinto.

For more on Japan's many Shinto schools of thought, see Shinto Schools & Sects (this site).

(a branch of Nichiren faith), and Yoshida Shinto. REFERENCES:

Yoshida Shinto. Academic school of Shinto widely propogated from the late 16th century to the beginning of the Meiji Restoration (1868). Also known as Gempon Sogen Shinto (Fundamental, Elemental Shinto), Yuiitsu Shinto (One-and-Only Shinto), and Urabe Shinto. Says Kokugakuin University: "The Yoshida family was in ancient times a family of diviners serving the court (it was a branch of the Urabe clan, court specialists in tortoise shell divination, which originated with Urabe Hiramaro in the 9th century). They later served as priests at Yoshida Jinja and Hirano Jinja in Kyoto. The Shinto traditions preserved by that family for generations were summarized and systematized by Yoshida Kanetomo (1435-1511). Yoshida Shinto expounds the unity of Shinto, Buddhism, and Confucianism, with Shinto as the basic factor. It recognizes the external existence of kami and also sees kami dwelling internally in the individual soul. It also emphasizes purity and cleanliness. Yoshida Shinto teachings were propagated throughout the country, influencing appointments to the priesthood and decisions regarding religious ceremonies."

For more on Japan's many Shinto schools of thought, see Shinto Schools & Sects (this site). It prospered until the forced separation of combinatory Buddha-Kami cults and institutions (Shinbutsu Bunri 神仏分離) during the Meiji Restoration of the latter half of the 19th century, when the government banned the veneration of kami under Buddhist names. The 30-kami cult has never recovered from the onslaught. Today it is a little-known and largely ignored grouping of deities from old Japan despite its continued veneration at some Nichiren temples REFERENCES:

Some temples of the Hokke (Lotus) school still hold events wherein the 30 kami, along with Kishimonjin and the 10 Rasetsu female demons, are venerated.

(see 2nd photo in right column for an example).

This 30-kami grouping is a purely Japanese convention, one that originated with the combinatory Buddha-Kami practices of Japan's Tendai sect. Nonetheless, its conceptual basis and development probably stems from earlier Chinese influences. Most scholars believe that a similar grouping, called the Secret Buddha of the 30 Days of the Month, originated in China around the 10th century, and then spread to Japan. This Chinese grouping may have sparked the development of Japan's 30-kami set, but further research is needed to determine if the two sets are related.

SANJŪBANJIN IN KYOTO (14th & 15th Centuries)

The Sanjūbanjin cult gained popularity in and around the capital of Kyoto in the 14th and 15th centuries thanks largely to the efforts of Nichizō 日像 (1269-1342), a disciple of Nichiren. Nichizō strove to expand Hokke Shinto REFERENCES:

Hokke Shinto. Literally "Lotus Shinto," a syncretic form that sprang from the Nichiren Sect of Buddhism. The Nichiren sect originated in the Kamakura era (1185 to 1332) and preaches that unmitigated faith in the Lotus Sutra is the sole means of liberation and salvation. Hokke (Lotus) Shinto did not gain prominence until the 14th and 15th centuries. It includes worship of the Sanjubanshin (30 Tutelary Deities of the Lotus Sutra) and belief that the deities will protect or abandon the nation based on the people's practice (or neglect) of the teachings in the Lotus Sutra. The development of Lotus Shinto was strongly influenced by Yoshida Shinto.

For more on Japan's many Shinto schools of thought, see Shinto Schools & Sects (this site).

in the capital by establishing ties with Japan's most powerful shrines and promoting veneration of their resident kami. This strategy was politically astute and extremely effective -- for the vast majority of the Sanjūbanjin hailed from the capital region and already enjoyed independent popularity among Kyoto clerics and residents (e.g., Kyoto-based kami include Hachiman, Kamo, Matsunō, Ōhara, Hirano, Inari, Gion, Sekisan, Kitano, Ebumi, and Kibune, while just outside Kyoto, at the Mt. Hiei temple-shrine multiplex protecting the capital, reside Ō-Hiei, Ko-Hiei, Shōshinji, Kyakujin, and Hachiōji). See below Sanjūbanjin Shrines In or Near the Capital.

In the 15th century, doctrinal debates between Hokke Shinto REFERENCES:

Hokke Shinto. Literally "Lotus Shinto," a syncretic form that sprang from the Nichiren Sect of Buddhism. The Nichiren sect originated in the Kamakura era (1185 to 1332) and preaches that unmitigated faith in the Lotus Sutra is the sole means of liberation and salvation. Hokke (Lotus) Shinto did not gain prominence until the 14th and 15th centuries. It includes worship of the Sanjubanshin (30 Tutelary Deities of the Lotus Sutra) and belief that the deities will protect or abandon the nation based on the people's practice (or neglect) of the teachings in the Lotus Sutra. The development of Lotus Shinto was strongly influenced by Yoshida Shinto.

For more on Japan's many Shinto schools of thought, see Shinto Schools & Sects (this site). and Yoshida Kanetomo 吉田兼倶 (1435-1511; founder of Yoshida ShintoREFERENCES:

Yoshida Shinto. Academic school of Shinto widely propogated from the late 16th century to the beginning of the Meiji Restoration (1868). Also known as Gempon Sogen Shinto (Fundamental, Elemental Shinto), Yuiitsu Shinto (One-and-Only Shinto), and Urabe Shinto. Says Kokugakuin University: "The Yoshida family was in ancient times a family of diviners serving the court (it was a branch of the Urabe clan, court specialists in tortoise shell divination, which originated with Urabe Hiramaro in the 9th century). They later served as priests at Yoshida Jinja and Hirano Jinja in Kyoto. The Shinto traditions preserved by that family for generations were summarized and systematized by Yoshida Kanetomo (1435-1511). Yoshida Shinto expounds the unity of Shinto, Buddhism, and Confucianism, with Shinto as the basic factor. It recognizes the external existence of kami and also sees kami dwelling internally in the individual soul. It also emphasizes purity and cleanliness. Yoshida Shinto teachings were propagated throughout the country, influencing appointments to the priesthood and decisions regarding religious ceremonies."

For more on Japan's many Shinto schools of thought, see Shinto Schools & Sects (this site). ) sparked further development and dissemination of the 30-kami set, with the Yoshida school in particular creating all new kami groupings thereafter. The Yoshida school attempted to claim authority over Sanjūbanjin worship by fabricating the origin of the group and claiming that the 30 kami worshipped by Hokke adherents was derived from Kanetomo's family ancestors. The two schools both cooperated and competed, but more importantly, their debates prompted the Hokke school to develop its own consistent theory about the proper worship of the kami and the meaning of Buddha-Kami syncretism. Most scholars believe the dispute brought benefits to both lineages (Yoshida and Hokke) by cyrstallizing their discourse. <source Lucia Dolce REFERENCES:

Dolce, Lucia. Hokke Shinto. Kami in the Nichiren Tradition. In: Teeuwen, M. and Rambelli, F., (eds.), Buddhas and Kami in Japan. Honji Suijaku as a Combinatory Paradigm. Curzon Routledge, 2003, pp. 222-54. >

During this period, the Sanjūbanjin begin to appear regularly in texts. For example, they are listed in the 14th-century Kokanzenji-roku 虎関禅師録 (Records of Zen Teacher Koganshiren 虎関師練; 1278-1346; a Rinzai-sect monk) and in the mid-15th-century text Gaun-nikken-roku 臥雲日件録, a diary by Rinzai-sect monk Zuikei Shūhō 瑞渓周鳳 (1392-1473).

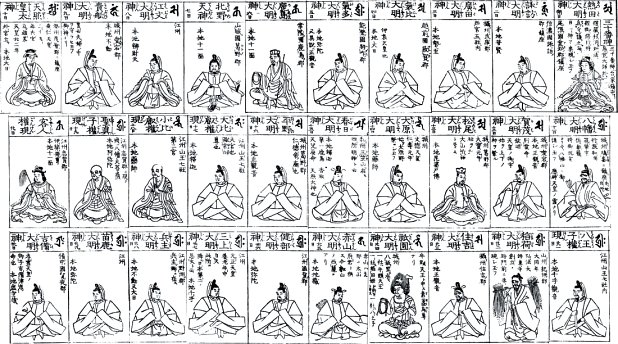

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

Sanjūbanshin or Sanjūbanjin 三十番神

The Thirty Tutelaries of the Lotus Sutra as appearing in the Butsuzō-zu-i 仏像図彙,

the "Illustrated Compendium of Buddhist Images." First published in 1690 (Genroku 元禄 3).

Above images compiled and translated by Mark Schumacher from the expanded 1783 version.

Both the 1690 and 1783 versions include this grouping, although some of the images are different.

The modern-day reprint (2005) of the enlarged Meiji-era version includes lengthy Japanese-language

commentary by Itō Takemi 伊藤武美 (b. 1927). Meiji-era Butsuzō-zu-i available at this online store (J-site)

|

TABLE 1. Thirty Kami Tutelaries of the Lotus Sutra

Most common grouping of the thirty kami <source: Butsuzo-zui>

H = Honji (original Buddhist manifestation) as given in the Butsuzo-zui (1783 version)

C = Corresponding Deity among Secret Buddhist Deities of the 30 Days of Month (1783 Butsuzo-zui)

|

|

Da y

|

Kami

Name

|

Buddhist Counterpart Honji 本地

|

Main Shrine, Kami

Description & Associations

|

|

1

|

Atsuta Daimyōjin

熱田大明神

|

H = Dainichi 大日如来

C = Jōkō Butsu 定光佛

|

Nagoya (Aichi). Atsuta Jingū Shrine 熱田神宮 (aka Yatsurugi), which supposedly houses the Kusanagi sacred sword 草薙の剣 (one of three imperial regalia); approximately. 2000 "emanation shrines" (bunsha) in Japan. Atsuta Shinkō. Also see ES. A female kami; appears in many literary works since the Heian era, e.g., as the lover of Emperor Genso in To-no-Genso 唐玄宗. Honji-Suijaku J-site. Other keywords 尾張国愛知郡.

|

|

2

|

Suwa Daimyōjin

諏訪大明神

|

H = Fugen 普賢菩薩

C = Tōmyō Butsu 燈明佛

|

Suwako (Nagano). Suwa Taisha 諏訪大社; a warrior shrine in eastern Japan. Its many nationwide shrines are devoted to the kami of wind & water (fūsuishin), battle (gunshin), blacksmithing (kajishin) and others; in some texts, he assisted Empress Jingū in her military campaign in Korea. Ref. Suwa Shinkō. Other keywords 信濃国諏訪郡.

|

|

3

|

Hirota Daimyōjin

広田大明神

|

H = Seishi 勢至菩薩

C = Tahō Butsu 多寶佛

|

Nishinomiya City (Hyōgo). Hirota Jinja 広田神社. Had helped the state in the suppression of rebels and bandits. One of the Nijūnisha 二十二社 (22 Shrines). Other keywords 摂州武庫郡西宮五社.

|

|

4

|

Kehi Daimyōjin

気比大明神

|

H = Dainichi 大日如来

C = Ashuku Butsu 阿閦佛

|

Tsuruga City (Fukui). Kehi Jingū 気比神宮. Tsuruga is a seaport town, and the Kehi Shrine is dedicated to Kehi Ōkami, who was once widely worshipped in northeast Honshu; the kami of boatmen, safety at sea, fishing families, and farmers; the Kehi cult began around same time as Hachiman cult (#11); tutelary deity of the Fujiwara clan; brought to Nara (Tōdaiji) to enlist the protection & endorsement of Japan's myriad kami. Other keywords 越前国敦賀郡.

|

|

5

|

Keta Daimyōjin

気多大明神

|

H = Amida 阿弥陀如来

H = Shō Kannon 正聖観音

C = Miroku Butsu 彌勒佛

|

Hakui City (Ishikawa). Keta Taisha Shrine 気多大社, which venerates Ōnamuchi no Mikoto 大巳貴命 (agricultural deity; also known as Ōkuninushi no Mikoto 大国主命 or Ōbie no Kami 大比叡神; also read Ōhiegami; the land-forming kami). Other keywords 能登国羽佐郡.

|

|

6

|

Kashima Daimyōjin

鹿島大明神

aka

Takemikazuchi

建御雷神

|

H = Jūichimen Kannon

十一面観音

C = Nimantōmyō Butsu

二萬燈明佛

|

Kashima City (Ibaraki). Kashima Jingū 鹿島神宮, once the most powerful warrior shirne in eastern Japan (常陸国鹿島郡). This kami also enshrined at Kasuga Taisha (Nara); appears as myōjin and gongen; warrior deity, thunder god, sword spirit, queller of earthquakes. Honji may also include Fukūkenjaku Kannon.

|

|

7

|

Kitano Tenjin

北野天神

|

H = Jūichimen Kannon

十一面観音

C = Sanmantōmyō Butsu

三萬燈明佛

|

Kyoto. Kitano Tenmangū 北野天満宮. One of 12 tutelaries of Mt. Hiei; Kitano Tenjin is a manifestation of Sugawara Michizane 菅原道真 (845-903), who was deified to passify his spirit; Kitano's main three shrines are located in Hōfu (Yamaguchi), Kyoto, and Dazaifu (Fukuoka). Ref. Tenjin Shinkō. One of the Nijūnisha 二十二社 (The 22 Shrines). Other keywords 山城国葛野郡.

|

|

8

|

Ebumi Daimyōjin

江文大明神

|

H = Benzaiten 弁才天

C = Yakushi 薬師如来

|

A kami from Gōshū 江州 (modern-day Shiga Prefecture) installed at Ebumi Jinja Shrine 江文神社 in Sakyo Ward 左京区, near Kyoto city, in an area formerly known as Mt. Ebumi (now known as Mt. Konpira in Kyoto). Today largely conflated with Benzaiten. The shrine initially venerated Ubusuna Kami 産土神, a protective land and food deity. Today it worships Ukanomitama no mikoto (Kojiki = 宇迦之御魂命, Nikon Shoki = 倉稲魂尊), the kami of grains and foodstuffs. Ebumi Daimyōjin is also one of 12 tutelaries of Mt. Hiei.

|

|

9

|

Kifune Daimyōjin

貴船大明神

or 貴布禰

|

H = Fudō Myō-ō 不動明王

C = Daitsūchishō Butsu

大通智勝佛

|

Kyoto. Kibune Jinja 貴船神社. Shrine kami were responsible for the sources of water in Kyoto. One of the Nijūnisha 二十二社 (The 22 Shrines). Other keywords 城州愛宕郡.

|

|

10

|

Amaterasu

Ōmikami

天照皇太神

|

H = Dainichi 大日如来

C = Nichigetsu Tōmyō

Butsu 日月燈明佛

|

Ise Jingū 伊勢神宮 (Mie). Imperial ancestor goddess. One of 12 tutelaries of Mt. Hiei; in Nichren sect, she is the central deity, equivalent to Shaka; 1st lord of the country of Japan; first kami in Ennin's list. One of the Nijūnisha 二十二社 (The 22 Shrines). Amaterasu may also manifest as Yakushi, Shaka, Kannon, or Benzaiten. Other keywords 勢州度會郡.

|

|

11

|

Hachiman Daimyōjin

八幡大明神

|

H = Amida 阿弥陀如来

C = Kangi Butsu 歓喜佛

Hachiman also

embodies the spirit of

Emperor Ojin 應神天皇.

|

Kyoto. Iwashimizu Hachimangū 石清水八幡宮. Powerful kami who played a great oracular function in state affairs as early as the 7C; by the 9C was awarded status of Bodhisattva; considered an imperial ancestor, protector of the emperor; by the 13C, became the guardian of warriors and tutelary deity of the Minamoto clan; in Nichiren sect, the 2nd most important kami after Amaterasu; one of 12 tutelaries of Mt. Hiei; 2nd kami in Ennin's list. One of the Nijūnisha 二十二社 (The 22 Shrines). Other keywords 城州鳩峯.

|

|

12

|

Kamo Daimyōjin

加茂大明神

|

H = Shō Kannon 聖観音

C = Nanshō Butsu 難勝佛

|

Kyoto. Kamo Jinja 賀茂神社. The Upper and Lower Kamo shrines housed the tutelary deities for the entire capital (Kyoto). One of the Nijūnisha 二十二社 (The 22 Shrines). Other keywords 城州愛宕郡.

|

|

13

|

Matsunō Daimyōjin

松尾大明神

|

H = Bibashi Butsu

毘婆尸佛

C = Kokūzō 虚空蔵菩薩

|

Kyoto. Matsunō Taisha 松尾大社. Protects the capital and the emperor. One of the Nijūnisha 二十二社 (The 22 Shrines). Bibashi Butsu is the first of Seven Buddha 七佛 of the Past 七佛. Bibashi = Vipaśyin (Skt). Other keywords 城州葛野郡.

|

|

14

|

Ōhara Daimyōjin

大原大明神

|

H = Yakushi 薬師如来

C = Fugen 普賢菩薩

|

Kyoto. Ōharano Jinja 大原野神社. Shrine associated with the Fujiwara clan. One of the Nijūnisha 二十二社 (22 Shrines). Yakushi is the Medicine Tathāgata, Healing Buddha. Other keywords 尾張国愛知郡.

|

|

15

|

Kasuga Daimyōjin

春日大明神

|

H = Shaka 釈迦如来

Skt. = Śākyamuni

C = Amida 阿彌陀佛

|

Nara City. Kasuga Taisha 春日大社, a major temple-shrine multiplex. Kasuga Shrine is one of the Nijūnisha 二十二社 (The 22 Shrines) and associated with the Fujiwara family. It also venerates #6 Kashima Daimyōjin; Katori 香取, Amenokoyane 天児屋命, and #10 Amaterasu. These deities may appear as Kasuga Gongen. Other keywords 和州三笠山.

|

|

16

|

Hirano Daimyōjin

平野大明神

|

H = Shō Kannon 聖観音

C = Darani 陀羅尼菩薩

|

Kyoto. Hirano Jinja 平野神社. Protects the capital and emperor. One of 12 tutelaries of Mt. Hiei. One of the Nijūnisha 二十二社 (The 22 Shrines). Other keywords 城州葛野郡・仁徳帝廟.

|

|

17

|

Ō-Hiei Gongen

大比叡権現

|

H = Shaka 釈迦如来

C = Ryūju 龍樹菩薩

|

Ōtsu. Mt. Hiei deity; aka Ōkuninushi no mikoto 大国主命, Ōnamuchi no kami 大己貴神, Ōmononushi 大物主, Ōbie no kami 大比叡神; also read Ohiegami; land-forming, land-creating, agricultural kami; appears in the Kojiki 古事記 and other early texts; brought from Mt. Miwa 三輪 (Nara) in 668 by Emperor Tenji 天智 (626-671), whose capital was in Ōtsu 大津 (near Kyoto & Lake Biwa). One of the Nijūnisha 二十二社 (The 22 Shrines). The primary shrine at the Mt. Hiei complex is Ōmiya 大宮 or Higashimotomiya 東本宮. Other keywords 江州山王七社 大宮権現

|

|

18

|

Ko-Hiei Gongen

小比叡権現

|

H = Yakushi 薬師如来

C = Kanzeon 観世音菩薩

|

Ōtsu. Mt. Hiei deity; aka Ninomiya 二宮, Sannō 山王, Ōyamagui 大山咋 (original deity or jinushigami 地主神 of Mt. Hiei), Kobie no kami 小比叡神 (also read Kohiegami); mountain kami, kami of brewing; mentioned in the Kojiki 古事記 of 712; Saichō 最澄 (766-822) gave Ōyamagui the name Sannō (which derives from Chinese god who protects Mt. Tientai (Jp. Tendai 天台) in China. The secondary shrine at the Mt. Hiei complex is Ninomiya 二宮 or Nishimotomiya 西本宮. Other keywords 江州山王七社第二宮

|

|

19

|

Shōshinji Gongen

聖真子権現

|

H = Amida 阿弥陀如来

C = Nikkō 日光菩薩

|

Ōtsu. Mt. Hiei deity. Also read Shōshinshi. A male manifestation of female kami Tagori Hime 田心姫神 <Tobifudo>, one of three Munakata female deities guarding the nation, the imperial house, safety at sea, and bountiful catches. Her main sanctuary is in Okitsumiya 沖津宮 on Okinoshima island 沖ノ島 at the southwestern tip of the Sea of Japan. In another tradition, Tagori Hime is the kami of agriculture and weaving. The third shrine at the Mt. Hiei complex is Shōshinji 聖真子 or Usamiya 宇佐宮. Other keywords 江州志賀郡

|

|

20

|

Kyakujin Gongen

客人権現

One of the

Seven Sannō

Gongen

山王七社

|

H = Jūichimen Kannon

十一面観音

C = Gakkō 月光菩薩

|

Ōtsu. Mt. Hiei deity. Female. Also read Marōdogami 客(人)神, lit. = guest kami; deity of Mt. Hakusan in NW Honshu, a major Buddha-Kami cult center ruled by Enryakuji Temple 延暦寺 on Mt. Hiei 比叡 starting in the 12 century; legend says she appeared at the foot of Hachiōjisan 八王子山, a small hill near the base of Mt. Hiei; since then seen as a protective deity of Mt. Hiei; typically shown carrying a fly whisk (hossu 払子) to brush away insects (obstacles) without slaying life; thus an instrument symbolizing obedience to Buddhist law. Enshrined at Hakusanmiya 白山宮 Shrine at Mt. Hiei, also known as Shirayama Hime Jinja 日吉大社白山姫神社. Other keywords 江州志賀郡.

|

|

21

|

Hachiōji Gongen

八王子権現

|

H = Senju Kannon

千手觀音

C = Mujini 無盡意菩薩

|

Ōtsu. Mt. Hiei deity. Kami of a small hill near the foot of Mt. Hiei called Hachiōjisan 八王子山 . As one of the 30 Kami Protecting the Imperial Palace, his honji is Mujini Bosatsu 無盡意菩薩 (a real monk-translator from China active in the 4th-5th century). The fifth shrine at the Mt. Hiei complex is Hachiōji 八王子 or Ōji / Ushiomiya 牛尾宮. Other keywords 江州山王七社.

|

|

22

|

Inari Daimyōjin

稲荷大明神

|

H = Nyoirin Kannon

如意輪観音

C = Semu-i 施無畏菩薩

|

Kyoto. Fushimi Inari Taisha 伏見稲荷大社, which also venerates Ukanomitama no mikoto (Kojiki = 宇迦之御魂命, Nikon Shoki = 倉稲魂尊), the kami of grains and foodstuffs. Inari is the kami of rice and agriculture, whose messenger is the fox. Over 30,000 Inari shrines nationwide, making Inari one of Japan's most popular deities. One of the Nijūnisha 二十二社 (The 22 Shrines). Inari protects the capital and emperor. Kūkai introduced him to the all-important Tōji Temple 東寺 complex in Kyoto as a protective kami; also associated with Benzaiten, Uga Benzaiten, and Dakini. Other keywords 山州紀伊郡.

|

|

23

|

Sumiyoshi Daimyōjin

住吉大明神

|

H = Shō Kannon 聖観音

C = Daiseishi 大勢至菩薩

|

Osaka. Sumiyoshi Taisha 住吉大社. Considered a guardian deity of sea farers, fishing, those who battle on the sea, waka poetry, and agriculture <LD> One of the Nijūnisha 二十二社 (The 22 Shrines). Associated with foreign relations, sea travel, and propitiated for calm int'l relations. Ref. Other keywords 攝州住吉郡.

|

|

24

|

Gion Daimyōjin

祇園大明神

Identified as a deity from India; although some legends say he originated at Ox-Head Mountain in Korea.

|

H = Yakushi 薬師如来

C = Jizō 地蔵菩薩

|

Kyoto. Yasaka Jinja 八坂神社. Identified with Gozu Tennō 牛頭天王 (Skt. = Gavagriva); also called Gion Tenjin 祇園天神; Gozu Tennō was the protective deity of Jetavana Grove (Jp. = Gion Shōja 祇園精舎), the first Buddhist monastery in India; appears in many forms, most commonly as wrathful figure with ox head mounted atop his head; one of 12 tutelaries of Mt. Hiei; also associated with Susano'o 素盞嗚尊; an epidemic deity & talisman to ward off disease; also worshipped at Kasuga Shrine in Nara. One of the Nijūnisha 二十二社 (The 22 Shrines). This syncretic deity was considered a Buddhist intrusion that was abolished from shrines after the forced separation of Buddhism & Shintoism in the Meiji period. Other keywords 城州八坂里.

|

|

25

|

Sekisan Daimyōjin

赤山大明神

|

H = Jizō 地蔵菩薩

C = Monju 文殊菩薩

|

Kyoto. Hiei-zan Seiroku 比叡山西麓, Sekisan Zen-in 赤山禅院, whose main object of veneration is Taizanfukun 泰山府君 (or 太 山府君), a deity of Taoist origin from China who rules the underworld. In this sense, Jizō is an appropriate honji, for Jizō acts as a protector of souls undergoing judgement in the afterlife. Other keywords 城州八坂里.

|

|

26

|

Takebe Daimyōjin

建部大明神

|

H = Amida 阿弥陀如来

C = Yakujō 薬上菩薩

|

Ōtsu. Takebe Taisha Shrine 建部大社. This shrine worships various deities, including Prince Yamato Takeru 日本武尊 (12th legendary emperor) and Amano Akarutama no Mikoto 天明玉命. Other keywords 江州滋賀郡.

|

|

27

|

Mikami Daimyōjin

三上大明神

|

H = Senju Kannon

千手觀音

C = Roshana 盧遮那佛

|

Yasu-cho (Shiga). Mikami Jinja 御上神社. One of 12 tutelaries of Mt. Hiei. Today the shrine is dedicated to Amenomikage no Kami 天之御影神, the god of Mt. Mikamiyama. One of the Myōjin Taisha 式内名大社 (Great Shrines of Famed Deities). REF. Other keywords 江州.

|

|

28

|

Hyōsu Daimyōjin

兵主大明神

|

H = Fudō 不動明王 or

Dainichi 大日如来

C = Dainichi 大日如来

|

Chūzu-chō (Shiga). Hyōsu Jinja 兵主神社, whose main kami of veneration is Ōnamuchi no Mikoto 大己貴命 (aka Ōkuninushi), a land-creating, land-forming kami mentioned in the Kojiki and Nihongi. Other keywords 江州野洲郡.

|

|

29

|

Nōka Daimyōjin

苗鹿大明神

|

H = Amida 阿弥陀如来

C = Yaku-ō 薬王菩薩

|

Ōtsu (Shiga). Nahaka Jinja Shrine 那波賀神社, which venerates Ima ono sukune 今雄宿禰, Ōnamuchi no Mikoto 大巳貴命, and other kami. In other versions of the 30 kami, Nōka is replaced by Naeka; the latter is one of 12 tutelaries of Mt. Hiei. Other keywords 江州.

|

|

30

|

Kibi Daimyōjin

吉備大明神

|

H = Kokūzō 虚空蔵菩薩

C = Shaka 釈迦如来

|

Okayama City (Okayama). Kibitsu Jinja 吉備津神社 is the most prominent Shintō shrine along the Sanyōdō (山陽道), the old road from Kyoto/Nara to Kyushu that follows the shoreline of the inland sea; this kami offered protection to the old provinces of Bizen, Bitchū, and Bingo; the shrine was forced to eliminate its Buddhist structures/ art and halt Buddha-Kami worship in the Meiji period; also worshipped at Mt. Koya. ES REF. Other keywords 備中国賀夜郡.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ten Different Versions of the 30 Kami of the 30 Days

|

|

|

SANJŪBANSHIN SHRINES

IN OR NEAR THE CAPITAL

The vast majority of the 30 kami reside in shrines near the capital region (Kyoto, Mt. Hiei or Ōtsu, Nara, Osaka). When Nichizō 日像 (1269-1342), a disciple of Nichiren, decided to expand the Hokke (Lotus) teachings in the capital region, he went to great lengths to establish ties with these shrines. Part of his strategy was to promote worship of the sanjūbanshin, for the kami in this grouping were already popular among clerics and residents of the capital.

KYOTO SHRINES (KAMI)

Iwashimizu Hachimangū 石清水八幡宮

Kamo Jinja 賀茂神社 (Kamo)

Matsunō Taisha 松尾大社 (Matsunō)

Ōharano Jinja 大原野神社 (Ōhara)

Hirano Jinja 平野神社 (Hirano)

Fushimi Inari Taisha 伏見稲荷大社 (Inari)

Yasaka Jinja 八坂神社 (Gion)

Sekisan Zen-in 赤山禅院 (Sekisan)

Kitano Tenmangū 北野天満宮 (Kitano)

Ebumi Jinja 江文神社 (Ebumi)

Kibune Jinja 貴船神社 (Kifune)

ŌTSU / SHIGA SHRINES (KAMI)

Hiei Taisha West 日吉大社 (Ō-Hiei)

Hiei Taisha East 日吉大社 (Ko-Hiei)

Hiei Taisha Usamiya 日吉大社 (Shōshinji)

Hiei Taisha Shirayama 白山姫神社 (Kyakujin)

Hiei Taisha Hachiōji 八王子社 (Hachiōji)

Takebe Taisha 建部大社 (Takebe)

Shinja 御上神社 (Mikami)

Hyōsu Jinja 兵主神社 (Hyōsu)

Nahaka Jinja 那波賀神社 (Nōka)

NARA SHRINES (KAMI)

Kasuga Taisha 春日大社 (Kasuga)

OSAKA SHRINES (KAMI)

Sumiyoshi Taisha 住吉大社 (Sumiyoshi)

HYŌGO SHRINES (KAMI)

Hirota Jinja 広田神社 (Hirota)

Sanjūbanshin Scroll, Dated 1580

Chishaku-in Temple 智積院

Nichiren Sect Temple

Gamagori City 蒲郡市 (Aichi Pref)

Photo this J-site

|

|

Ten different Sanjūbanjin groupings developed over the centuries out of Tendai syncretism, Hokke (Nichiren) Shintō, and Yoshida Shintō. Two types are prevalent. The first type reflects the grouping's origin within the Tendai sect, which invoked the 30 kami to protect the Lotus Sutra during ritual copyings of that scripture, although in later centuries the 30 kami served as guardians of other Buddhist scriptures as well. This first type is commonly considered the prototype for all subsequent groupings. The second type includes those promoted by Yoshida Shintō, which relate more specifically to the political world (protecting the capital, the imperial palace, the nation, and heaven/earth/eight directions). In addition, the Nichiren school associated its own protective deities with the 30-kami set, giving rise to a distinctive genre of mandala paintings that included the Sanjūbanjin, Kishimojin 鬼子母神 (demon mother who repents and embraces the teachings of the Lotus Sutra), Shichimen Daimyōjin 七面大明神 (guardian deity of the sect's main temple on Mt. Minobu), and the Rasetsu 羅刹 (10 female demons who convert and thereafter pledge to protect devotees of the Lotus Sutra). The ten groupings as commonly known today are: Ten different Sanjūbanjin groupings developed over the centuries out of Tendai syncretism, Hokke (Nichiren) Shintō, and Yoshida Shintō. Two types are prevalent. The first type reflects the grouping's origin within the Tendai sect, which invoked the 30 kami to protect the Lotus Sutra during ritual copyings of that scripture, although in later centuries the 30 kami served as guardians of other Buddhist scriptures as well. This first type is commonly considered the prototype for all subsequent groupings. The second type includes those promoted by Yoshida Shintō, which relate more specifically to the political world (protecting the capital, the imperial palace, the nation, and heaven/earth/eight directions). In addition, the Nichiren school associated its own protective deities with the 30-kami set, giving rise to a distinctive genre of mandala paintings that included the Sanjūbanjin, Kishimojin 鬼子母神 (demon mother who repents and embraces the teachings of the Lotus Sutra), Shichimen Daimyōjin 七面大明神 (guardian deity of the sect's main temple on Mt. Minobu), and the Rasetsu 羅刹 (10 female demons who convert and thereafter pledge to protect devotees of the Lotus Sutra). The ten groupings as commonly known today are:

- Thirty tutelaries protecting the Lotus Sutra (Tendai sect). 法華守護の三十番神. Supposedly the kami solicited by Saichō 最澄 (767-822), the Japanese patriarch of Tendai in Japan. This grouping is considered apocryphal, for in the Chōkō Ninnō Hannyagyō Eshiki 長講仁王般若經會式 (T.74, p. 261, or DZ 4), a work attributed to Saichō, the patriarch mentions only six kami (Ōbie, Kobie, Kamo, Sumiyoshi, Kibi, and Kita).

- Thirty tutelaries protecting the Sutra of the Lotus of the Wonderful Dharma. 妙法経守護の三十番神. Those invoked by Tendai monk Ennin 円仁 (794-864) before he traveled to China to study Tendai teachings. Considered apocryphal, for records indicate that Ennin venerated only twelve kami, those associated with the twelve signs of the hours of the day (jūnishi 十二支). Ennin's list is said to start with Amaterasu and Hachiman. <Lucia Dolce, p 225

REFERENCES:

Dolce, Lucia (2003) Hokke Shinto. Kami in the Nichiren Tradition. In: Teeuwen, M. and Rambelli, F., (eds.), Buddhas and Kami in Japan. Honji Suijaku as a Combinatory Paradigm. Curzon Routledge, pp. 222-54.

>

- Thirty tutelaries protecting the Dharma (Buddhist Law). 如法守護の三十番神. The group of kami venerated by Tendai monk Ennin 円仁 (794-864) after he returned from China. Keywords: 如法経守護三十番神, Nyohōdō 如法堂, Yokawa 横川. See Table Two below for a complete listing.

Thirty tutelaries protecting the Lotus Sutra 法華経守護の三十番神. The most common grouping both in the past and today. Attributed to Nichiren, although he wrote nothing about them. Scholar Lucia Dolce REFERENCES:

Dolce, Lucia (2003) Hokke Shinto. Kami in the Nichiren Tradition. In: Teeuwen, M. and Rambelli, F., (eds.), Buddhas and Kami in Japan. Honji Suijaku as a Combinatory Paradigm. Curzon Routledge, pp. 222-54.

See page 228, where Dolce says "Although Nichiren never mentioned the thirty kami, legends were later created to suggest that these deities had been part of the pantheon of the Hokke school since the time of its founder. One that can be found in early biographies of Nichiren recounts that the sanjubanjin appeared to Nichiren while he was reading the Lotus Sutra in the temple were he lived during his years of study on Mount Hiei. According to these sources, Nichiren wrote down the names of the deities and drew their images; these inscriptions are said to be the jinmyocho (kami register) kept at Myokaiji in Numazu, and the pictorial representation preserved at Rissh?ji in Yamanashi. 14 The story clearly is a later fabrication of sectarian hagiographers who wanted to trace back a current practice to the founder, but it was influential in reinforcing the worship of the sanj?banjin within the Hokke school."

Later on the same page, she says: "The development of a cult of the thirty deities may be more properly linked to the youngest disciple of Nichiren, Nichizo (1269-1342), who went to spread the teachings of Nichiren in the area of the capital. Evidence of his interest in the sanjubanjin comes from the mandalas that Nichizo drew." believes this set most likely emerged with the Hokke Shinto REFERENCES:

Hokke Shinto. Literally "Lotus Shinto," a syncretic form that sprang from the Nichiren Sect of Buddhism. The Nichiren sect originated in the Kamakura era (1185 to 1332) and preaches that unmitigated faith in the Lotus Sutra is the sole means of liberation and salvation. Hokke (Lotus) Shinto did not appear until the subsequent Muromachi period (1392 to 1568). It includes worship of the Sanjubanshin (30 Tutelary Deities of the Lotus Sutra) and belief that the deities will protect or abandon the nation based on the people's practice (or neglect) of the teachings in the Lotus Sutra. The development of Lotus Shinto was strongly influenced by Yoshida Shinto.

For more on Japan's many Shinto schools of thought, see Shinto Schools & Sects (this site). school of the 14th and 15th centuries, although the systematization of the sanjūbanjin is commonly attributed to Ryōshō 良正, superintendent (chōri 長吏) of Shuryōgon'in in the year 1073.

- Thirty tutelaries protecting the Humane Kings Sutra 仁王経. Attributed to 11th-century Tendai monk Ryōshō 良正.

- Thirty tutelaries protecting heaven, earth, and the eight directions (Tenjin Chigi 天神地祇 or 天地擁護三十番神). Attributed to Yoshida Shintō circles. Consists of 32 deities in a 4 X 8 matrix. The four groups (of eight deities each) are east, north, west, and south. See list at this outside J-site.

- Thirty tutelaries protecting the Naishidokoro 内侍所 (inner sanctum of imperial palace, the location of the sacred mirror). This grouping is known as the Naishidokoro Sanjūbanshin 内侍所三十番神. It is attributed to Yoshida Shintō circles. Includes 32 deities. See list at this outside J-site.

- Thirty tutelaries protecting the ruler's castle 王城守護三十番神. Attributed to Yoshida Shintō circles. Composed of 32 deities in a 4 x 8 matrix. The four groups of eight deities are classified as (1) left, blue-green dragon; (2) front, red bird; (3) right, white tiger; and (4) back, turtle. See list at this outside J-site. These four creatures are ancient Chinese mythical animals associated with the four cardinal directions. See Four Guardians of the Four Compass Directions for details.

- Thirty tutelaries protecting the nation 吾国守護三十番神. Attributed to Yoshida Shintō circles.

- Thirty tutelaries protecting the imperial palace 禁闕守護 (Kinketsu Shugo). Attributed to Yoshida Shintō circles; used as well by Ryōbu Shinto 両部神道 (Shingon Sect 真言系); sometimes includes 32 kami, yet still referred to as Sanjūbanshin (30-Kami Group). See Table Three below for a complete listing.

<sources: gleaned from various resources, including J-site #1 and J-site #2>

|

|

|

TABLE TWO

30 Kami Protecting the Dharma (Law)

Nyohō Shugo Sanjūbanshin

如法守護三十番神

The number in parenthesis refers to

the deity's position in the most common

grouping of the 30 Kami (Table One)

|

TABLE THREE

30 Kami Protecting the Imperial Palace

Kinketsu Shugo Sanjūbanshin

禁闕守護三十番神

The number in parenthesis refers to

the deity's position in the most common

grouping of the 30 Kami (Table One)

|

|

|

|

- Amaterasu Ōmikami (10), Ise City (Mie)

Ise Jingū 伊勢神宮

- Hachiman Daimyōjin (11) Kyoto

Iwashimizu Hachimangū 石清水八幡宮

- Kamo Daimyōjin (12), Kyoto

Kamo Jinja 賀茂神社

- Matsunō Daimyōjin (13), Kyoto

Matsunō Taisha 松尾大社

- Hirano Daimyōjin (16), Kyoto

Hirano Jinja 平野神社

- Inari Daimyōjin (22), Kyoto

Fushimi Inari Taisha 伏見稲荷大社

- Kasuga Daimyōjin (15), Nara

Kasuga Taisha 春日大社

- Ō-Hiei Daimyōjin (17), Ōtsu

Hiei (Hiyoshi) Taisha West 日吉大社西本宮

- Ko-Hiei Daimyōjin (18), Ōtsu

Hiei (Hiyoshi) Taisha East 日吉大社東本宮

- Shōshinji Gongen (19), Ōtsu

Hiei (Hiyoshi) Taisha Usamiya 日吉大社宇佐宮

- Kyakujin Daimyōjin (20), Ōtsu

Hiei Taisha Shirayama Hime 日吉大社白山姫神社

- Hachiōji Gongen (21), Ōtsu

Hiei (Hiyoshi) Taisha Hachiōji 日吉大社八王子社

- Ōhara Daimyōjin (14), Kyoto

Ōharano Jinja 大原野神社

- Ōmiwa 大神, Sakurai City (Nara)

Ōmiwa Jinja 大神神社)

- Ishi-ue Myōjin 石上明神, Tenri City (Nara)

Isonokami Jingū 石上神宮

- Ōyamato 大倭, Tenri City (Nara)

Ōyamato Jinja 大和神社

- Hirose 広瀬, Kawai-chō (Nara)

Hirose Jinja 広瀬神社

- Tatta 竜田, Sangōchō 三郷町 (Nara)

Tatta Jinja 龍田神社

- Sumiyoshi Daimyōjin (23), Osaka

Sumiyoshi Taisha 住吉大社

- Kashima Daimyōjin (6), Kashima City (Ibaraki)

Kashima Jingū 鹿島神宮

- Sekisan Daimyōjin (25), Kyoto

Sekisan Zen-in 赤山禅院

- Takebe Daimyōjin (26), Ōtsu

Takebe Taisha 建部大社

- Mikami Daimyōjin (27), Yasu-cho (Shiga)

Mikami Shinja 御上神社

- Hyōsu Daimyōjin (28), Chūzu-chō (Shiga)

Hyōsu Jinja 兵主神社

- Nōka Daimyōjin (29), Ōtsu (Shiga)

Nahaka Jinja 那波賀神社

- Kibi Daimyōjin (30), Okayama City(Okayama)

Kibitsu Jinja 吉備津神社

- Atsuta Daimyōjin (1), Nagoya City (Aichi)

Atsuta Jingū 熱田神宮

- Suwa Daimyōjin (2), Suwako (Nagano)

Suwa Taisha 諏訪大社

- Hirota Daimyōjin (3), Nishinomiya City (Hyōgo)

Hirota Jinja 広田神社

- Kehi Daimyōjin (4), Tsuruga City (Fukui)

Kehi Jingū 気比神宮

Source: this outside J-site (第七)

|

- Amaterasu Ōmikami (10), Ise City (Mie)

Ise Jingū 伊勢神宮

- Hachiman Daimyōjin (11) Kyoto

Iwashimizu Hachimangū 石清水八幡宮

- Kamo Daimyōjin (12), Kyoto

Kamo Jinja 賀茂神社

- Matsunō Daimyōjin (13), Kyoto

Matsunō Taisha 松尾大社

- Ōhara Daimyōjin (14), Kyoto

Ōharano Jinja 大原野神社

- Kasuga Daimyōjin (15), Nara City

Kasuga Taisha 春日大社

- Hirano Daimyōjin (16), Kyoto

Hirano Jinja 平野神社

- Ō-Hiei Daimyōjin (17), Ōtsu

Hiei (Hiyoshi) Taisha West 日吉大社西本宮

- Ko-Hiei Daimyōjin (18), Ōtsu

Hiei (Hiyoshi) Taisha East 日吉大社東本宮

- Shōshinji Gongen (19), Ōtsu

Hiei (Hiyoshi) Taisha Usamiya 日吉大社宇佐宮

- Kyakujin Daimyōjin (20), Ōtsu

Hiei Taisha Shirayama Hime 日吉大社白山姫神社

- Hachiōji Gongen (21), Ōtsu

Hiei (Hiyoshi) Taisha Hachiōji 日吉大社八王子社

- Inari Daimyōjin (22), Kyoto

Fushimi Inari Taisha 伏見稲荷大社

- Sumiyoshi Daimyōjin (23), Osaka

Sumiyoshi Taisha 住吉大社

- Gion Daimyōjin (24), Kyoto

Yasaka Jinja 八坂神社

- Sekisan Daimyōjin (25), Kyoto

Sekisan Zen-in 赤山禅院

- Takebe Daimyōjin (26), Ōtsu

Takebe Taisha 建部大社

- Mikami Daimyōjin (27), Yasu-cho (Shiga)

Mikami Shinja 御上神社

- Hyōsu Daimyōjin (28), Chūzu-chō (Shiga)

Hyōsu Jinja 兵主神社

- Nōka Daimyōjin (29), Ōtsu (Shiga)

Nahaka Jinja 那波賀神社

- Kibi Daimyōjin (30), Okayama City (Okayama)

Kibitsu Jinja 吉備津神社

- Atsuta Daimyōjin (1), Nagoya (Aichi)

Atsuta Jingū 熱田神宮

- Suwa Daimyōjin (2), Suwako (Nagano)

Suwa Taisha 諏訪大社

- Hirota Daimyōjin (3), Nishinomiya City (Hyōgo)

Hirota Jinja 広田神社

- Kehi Daimyōjin (4), Tsuruga City (Fukui)

Kehi Jingū 気比神宮

- Keta Daimyōjin (5), Hakui City (Ishikawa)

Keta Taisha 気多大社

- Kashima Daimyōjin (6), Kashima City (Ibaraki)

Kashima Jingū 鹿島神宮

- Kitano Tenjin (7), Kyoto

Kitano Tenmangū 北野天満宮

- Ebumi Daimyōjin (8), Kyoto

Ebumi Jinja 江文神社

- Kifune Daimyōjin (9), Kyoto

Kibune Jinja 貴船神社

Source: this outside J-site (第五)

|

|

NOTE TABLE TWO. Says the Kokugakuin University Encyclopedia of Shinto: "Nijūnisha 二十二社 (The 22 Shrines). Twenty-two shrines (Ise, Iwashimuzu, Kamo, Matsuno-o, Hirano, Inari, Kasuga, Ōharano, Ōmiwa, Isonokami, Ōyamato, Hirose, Tatta, Sumiyoshi, Hie, Umenomiya, Yoshida, Hirota, Gion, Kitano, Niukawakami, Kibune) received special patronage from the imperial court beginning in the mid-Heian period and ending in the mid-Medieval period. [Many of these shrines are included in the above list.] In this case, it is common practice to refer to the two shrines Kamowakeikazura shrine and Kamomioya as one shrine, Kamo. All of these shrines are located in or around Kyoto and were primarily responsible for rain rituals, along with rites for stopping deluges, dispensing with rites during times of calamity and auspicious natural events, and performing rites during times of political and imperial crisis. Along with this role, these shrines took part in annual and twice-yearly rites for agricultural fecundity (these rites began after the mid-Heian period) and received offerings from the imperial court." For more on the Nijūnisha, also see Lecture Six, by Professor Okada at Kokugakuin University.

NOTE TABLES TWO & THREE. Amaterasu Ōmikami and Hachiman Daimyōjin appear in the first and second position in Table Two and in Table Three. In Table One, however, they appear much lower in the list (day 10 and day 11). This elevation to top status occurred in the 14th and 15th centuries, and clearly reflects the political agenda of Hokke Shintō (Nichiren affiliation) and Yoshida Shintō. Both denominations considered these two kami as Japan's most powerful deities -- as the "Lords of the Land of Japan" -- and therefore wished to place them at the top of the list.

|

|

|

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

Sanjūbanshin or Sanjūbanjin 三十番神

The Thirty Tutelaries of the Lotus Sutra, Wood

Kasuga Jinja Shrine in Warabi City 蕨市, Saitama Pref.

Carved between 1717-1736. Photo from Warabi City Web Site.

|

|

|

MORE ABOUT SANJŪBANSHIN 三十番神

|

|

|

|

Sanjūsanbanshin 三十番神画像, ICP

Color on silk, H 94.7 cm, W 39 cm

Muromachi Period 室町時代 (1566)

Daihōji Temple 大法寺, Takaoka City, Toyama Pref. Painting by Hasegawa Tōhaku 長谷川等伯 (1539-1610); aka

Hasegawa Shinshun 長谷川信春.

Photo from Temple's Web Site.

Closeup. Click to Enlarge.

Photo Kyoto Nat'l Museum

Closeup. Click to Enlarge.

Kami of Day 1 Atsuta Daimyōjin

Kami of Day 2 Suwa Daimyōjin

Photo Kyoto Nat'l Museum

Closeup. Click to Enlarge.

Kami of Day 15, 16, 17

Ō-Hiei Gongen 大比叡権現

also known as Ōbie no kami

Photo this J-site

Sanjūbanshin, Wood Statues.

No date given. Ryū Jinja Shrine 龍神社, Tomakomai City 苫小牧市, Hokkaido.

Now at 勇払恵比須神社.

Photo: Yūfutsu Ebisu Jinja Shrine

Sanjūbanjin dolls at Shōkakuji Temple

成覚寺 (Ōita Pref). Date unknown. The temple's highly improbably legend says, during the great fires that ravaged the area in 1883, Shōkakuji was the only structure left standing because the 30 deities appeared on the rooftop of the temple's main hall (Hondō 本堂).

Photo this J-site.

Sanjūbanjin Wooden Statues at Sanjūbanjingū Shrine 三十番神宮

Located in Tebiro 手広 (near Kamakura), this shrine is associated with the Nichiren sect, and holds an annual festival on October 9 dedicated to the Sanjūbanshin. The statues are enshired in a zushi (tabernacle) within the shrine's inner sanctuary. Photo from Kamakura Citizens Net (Japanese language only).

Sanjūbanshin

Kasuga Jinja Shrine (Warabi, Saitama)

Mid-Edo Era (carved between

1717-1736); Warabi City 蕨市,

Saitama Pref. Photo this J-site.

|

|

|

|

|

Says JAANUS (Japanese Architecture Says JAANUS (Japanese Architecture

and Art Net Users System)

Read Sanjūbanshin or Sanjūbanjin (Sanjubanjin, Sanjuubanjn). Various sets of thirty kami 神 who protect the nation's peace and people's happiness during the thirty days of the month. The origins of this concept are obscure, but are commonly traced to a story concerning the abbot Ennin 円仁 (794-864) in which he invited thirty principal Shintō deities (kami) to Mt. Hiei 比叡 in order to protect the copy of Lotus Sutra (HOKEKYŌ 法華経) which he had made under special ritual conditions and had enshrined at the Nyohōdō 如法堂 hall of Yokawa 横川 on the mountain. The earliest records of the Sanjūbanshin, however, date from the late 11th century and their cult is not prominent until the Muromachi period (14-15c). The Sanjūbanshin are shown in both groupings of sculptures and in paintings of the thirty deities arranged in rows. Most extant depictions show the set of protectors of the Lotus Sutra, and were hung as protective talismans especially during Tendai 天台 or Nichiren 日蓮 ceremonies. Early paintings tend to show the deities standing, while later paintings show them seated. There is a panel painting of the Sanjūbanshin dated 1433 in the Shirahige Jinja 白髭神社 in Moriyama 守山, Shiga prefecture. The kami and the day they serve vary according to the set, but include deities of Sannō 山王 (the shrine associated with Enryakuji 延暦寺 on Mt Hiei), others from near Lake Biwa 琵琶 and Kyoto, and famous deities from elsewhere in the country. A set of deities could protect the power of texts other than the Lotus Sutra, and more purely Shintō sets could protect the directions (although these could number 32 they were still called Sanjūbanshin). The significance of the cult was the general protection by powerful kami. The cult of the Sanjūbanshin of the Lotus Sutra was adopted in the Nichirenshū 日蓮宗, and within that sect it was connected with the cult of the ten daughters of the Rasetsu (Jūrasetsunyo 十羅刹女) who appear in the 26th chapter of the Lotus Sutra, Dharani (Jp:Daranibon 陀羅尼品), where they swear to protect those who practice the sutra and preach the Buddhist Law or Dharma.

Says Kokugakuin University,

Encyclopedia of Shinto

The Thirty Tutelaries, a cultic belief in thirty tutelary kami that alternate each day of the month to protect the Lotus Sutra and the Japanese nation. The cult is especially prevalent within the Nichiren sect. The conceptual ground for the cult originated in the Tendai sect on Mt. Hiei, based on the Lotus Sutra's nineteenth chapter, "The Benefits of the Teacher of the Law," and in the theory of tutelary deities found in the sutra Bussetsu Kanjō-kyō 仏説灌頂経 (Skt. = Abhiseka sutra; translated into Chinese in the early 4th century). Several traditions exist regarding the cult's origins. One states that the priest Jikaku Taishi 慈覚大師 (aka Ennin 円仁, 794-864) first invoked the deities at the time of the construction of the temple Shuryōgon'in 首楞厳院 in 829 (ref. late 11th-century Konjaku Monogatari 今昔物語, V11 and the Kamakura-era Genpei Seisuiki 源平盛衰記). Other traditions suggest that Ryōshō 良正, superintendent (chōri長吏) of Shuryōgon'in, invoked the deities as tutelaries of sutra copying in 1073 (ref. 13th-century Eigaku Yōki 叡岳要記 Important Records of Mt. Hiei, and the mid-14th century Suwa Daimyōjin Ekotoba 諏訪大明神絵詞 Pictorial Account of the Great Deity of Suwa). Still others state that Ennin invoked twelve of the kami while Ryōshō later set the number at thirty (ref. 15th-century Jingi Seisō 神祇正宗). The composition of the thirty deities thus appears to have varied depending on the teller of the story.

From the medieval period, the cult of thirty kami was adopted within the Nichiren sect, where they were called "the thirty tutelaries of the Lotus Sutra"; in time they came to hold an even more important place than they had held in Tendai. During a 1497 debate regarding the cult of thirty tutelaries, Yoshida Kanetomo 吉田兼倶 (1435-1511) of the medieval school of Yoshida Shintō claimed that the thirty tutelaries of the Nichiren Sect had originally been introduced to Nichiren by Kanetomo's distant ancestor Kanemasu. The Nichiren Sect made no clear response, and from that time, the Shinto theories accepted within the sect (called Hokke Shintō or "Lotus Shinto") came to be influenced by the then-current trends of the Yoshida school. The cult of thirty tutelaries continued to be observed within the Nichiren sect and came to occupy an important place within the group's views of Shinto. In contrast to the thirty tutelary kami of the Tendai and Nichiren sects, the Yoshida Shintō school developed its own cultic beliefs in various groups of thirty kami. These included the "thirty tutelaries of heaven and earth (天地擁護の三十番神)," the "thirty tutelaries of the naishidokoro (the inner sanctum of the imperial palace 内侍所の三十番神)," the "thirty tutelaries of the imperial capital (王城守護の三十番神)," the "thirty tutelaries of the nation (吾が国守護の三十番神)," and the "thirty tutelaries of the imperial palace (Kinketsu Shugo Sanjū Banshin 禁闕守護三十番神)." Of these various groupings, the thirty tutelaries of the imperial palace were the same kami as those found in earlier cultic groupings, while those in the others were entirely different, and based on theories unique to Yoshida Shintō. <quote by Itō Satoshi, Kokugakuin University, 2005/3/31>

Says A-to-Z Dictionary (this site)

Hokke Shintō 法華神道. Literally "Lotus Shintō," a syncretic form that sprang from the Nichiren Sect 日蓮宗 of Buddhism. The Nichiren sect originated in the Kamakura era (1185 to 1332) and preaches that unmitigated faith in the Lotus Sutra is the sole means of liberation and salvation. Lotus Shintō did not appear until the subsequent Muromachi period (1392 to 1568). It includes worship of the Sanjūbanshin 三十番神 (30 Tutelary Deities of the Lotus Sutra) and belief that the deities will protect or abandon the nation based on the people's practice (or neglect) of the teachings in the Lotus Sutra. The development of Lotus Shintō was strongly influenced by Yoshida Shintō.

Says Lucia Dolce in Buddhas & Kami in Japan: Honji Suijaku as a Combinatory Paradigm (pp. 225-226)

Tendai Rituals and the Sanjūbanjin. A set of thirty kami is first mentioned in relation to a specific ritual developed in the Tendai school: the practice of "copying the Lotus Sutra according to the prescribed method" (nyohōkyō 如法経). This copying involved a series of procedures focusing on the purity of the body and the material used to copy the scripture; devotion to the sutra was expressed by bowing three times for each character one copied. Preparations occupied most of the time spent on the ritual, subsidiary scriptures were also recited and copied, and the main sutra, the Lotus Sutra, was copied at the end, on an auspicious day. The practice was started by Ennin (792-862) and was later associated, in particular, with the Yokawa area of Mount Hiei. It is said that the sanjūbanjin manifested themselves to Ennin while he was performing this ritual, and thus became the tutelary deities of the practice. Records, however, indicate that Ennin venerated only twelve kami, associated to the twelve signs of the hours of the day (nijūshi), and that the sanjūbanjin were systematized and identified each with one day of the month only in the eleventh century. Small shrines dedicated to these kami were built in Yokawa [at Mt. Hiei], and statues of the thirty gods were placed in these shrines and in buildings surrounding the main hall. The worship of the sanjūbanjin continued in the Tendai school throughout the Heian and medieval periods, and also spread out from Mount Hiei to other sites where ritual copying of the Lotus Sutra took place. A medieval collection of rituals, the Mon'yōki 門葉記 [14th century], describes a number of assemblies for the performance of this practice (nyohōkyō no hōe 如法経の法会). The liturgical prescriptions include displaying a piece of paper with the names of the sanjūbanjin (jinmyōchō 神名帳); in one case this register is hung from the horizontal timber of the wall in front of the entrance to the practice hall, either the eastern wall or the northern wall, in other cases, the paper is stamped on the wall. Lists of the thirty kami are supplied, and the practitioners are also instructed to write down the names of the sanjūbanjin, to concentrate on the kami of that day and to read one fascicle of the sutra "to make the kami rejoice in the Dharma" (hōraku 法楽).

What was the origin of this fixed set of tutelary deities, and how did they become thirty? To have a fixed number of deities was not uncommon in Buddhism. The Guàndǐng jīng 灌頂經 [ca 5th century], for instance, mentions thirty-six "good gods" who protect men and women who rely on the Three Treasures. There also existed examples of banjin 番神, that is, deities assembled in a certain order and allocated to specific slots of time. In China in the tenth century thirty "secret buddhas" (mìfó 秘佛) were thought to protect the days of the month, and this belief spread to Japan in the medieval period, where the thirty deities were also known as "the buddha-names of the thirty days [of the month]" (sanjūnichi butsumyō). The Tendai school also used distinctive sets: "the five kami protecting Mt. Hiei," Ōbie, Obie (Ninomiya), Shōshinji, Marōdo (Hakusan) and Hachiōji, were venerated each for six days, in this order; four of these, together with Mikami, Ebumi, Naeka, Amaterasu, Hachiman, Gion, Kitano, and Hirano, formed the "twelve tutelary deities of Hiei," who were said to protect the devotee of the Lotus Sutra during the twelve hours of the day. These sets may be regarded as prototypes for the sanjūbanjin. <end quote, pp. 225-226>

Lucia Dolce REFERENCES:

Dolce, Lucia (2003) Hokke Shinto. Kami in the Nichiren Tradition. In: Teeuwen, M. and Rambelli, F., (eds.), Buddhas and Kami in Japan. Honji Suijaku as a Combinatory Paradigm. Curzon Routledge, pp. 222-54 adds an interesting dissection of the four characters of the term Sanjūbanshin 三十番神 (pages 243- 244), which she says reflects Tendai and Hokke ontology and expresses the notion that "reality is an interdependent unity, where the whole is comprised in one moment of thought." Below is her translation of a passage from page four of the 15th-century Banjin Mondōki 番神問答記:

- Three 三 (san) signifies the threefold truth (sandai 三諦, i.e., emptiness, conventional existence and middle way), which is identical (soku 卽) with the wonderful Dharma (myōhō 妙法)

- Ten 十(jū) indicates the ten worlds (jikkai 十界, i.e., the ten destinies of transmigration)

- Order 番 (ban) means that the ten worlds and the threefold truth are mutually encompassing (gogu 互具) and harmonious, and yet are not one

- Kami 神 (jin or shin) indicates that the original portion of the single mind (isshin honbun 一心) is the nature of the myriad dharmas (manpō jishō 萬法自性). This is what is called Sanjūbanjin. This is the wonderful essence of the Lotus and the body and mind (shikishin 識身) of the [Lotus] practitioner. The deities who protect and the sutra that is protected are one with the body and the mind of the [Lotus] practitioner.

SOURCES / REFERENCES

- Butsuzō zui 仏像図彙 (Illustrated Compendium of Buddhist Images). Published in 1690 (Genroku 元禄 3). A major Japanese dictionary of Buddhist iconography. Hundreds of black-and-white drawings, with deities classified into categories based on function and attributes. For an extant copy from 1690, visit the Tokyo Metropolitan Central Library. An expanded version, known as the Zōho Shoshū Butsuzō-zui 増補諸宗仏像図彙 (Enlarged Edition Encompassing Various Sects of the Illustrated Compendium of Buddhist Images), was published in 1783. View a digitized version (1796 reprint of the 1783 edition) at the Ehime University Library. Modern-day reprints of the expanded 1886 Meiji-era version, with commentary by Ito Takemi (b. 1927), are also available at this online store (J-site). In addition, see Buddhist Iconography in the Butsuzō-zui of Hidenobu (1783 enlarged version), translated into English by Anita Khanna, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, 2010.

- Centers of Consecration in Japan. By Meg Gentes, PhD.

- Daihōji Temple 大法寺, Takaoka City, Toyama Pref. PHOTO.

- Dolce, Lucia (2003) Hokke Shinto. Kami in the Nichiren Tradition. In: Teeuwen, M. and Rambelli, F., (eds.), Buddhas and Kami in Japan. Honji Suijaku as a Combinatory Paradigm. Curzon Routledge, pp. 222-54. Also see:

- Book Review: Paradigm Regained: Taking Syncretism Seriously, by D. Max Moerman. Reviewed work(s): Buddhas and Kami in Japan: Honji Suijaku as a Combinatory Paradigm by Mark Teeuwen; Fabio Rambelli. Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 59, No. 4 (Winter, 2004), pp. 525-533

- Hokkeshu.com. Sanjubanshin page, with information on Kishimonjin 鬼子母神 and the ten female Rasetsu demons 十羅刹.

- Honji Suijaku Main Menu 本地垂迹資料便覧. Japanese language site.

- JAANUS. Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System, Sanjūbanshin Entry

- Kamakura Citizens Net (KCN), Special Report on the Sanjūbanjingū Shrine 三十番神宮 located in Tebiro 手広 (near Kamakura). This shrine is associated with the Nichiren sect, and holds an annual festival on October 9 dedicated to the Sanjūbanshin. (J-site). See other related KCN page on Sanjūsanjingū.

- Kato, Genchi. A Study of Shinto: The Religion of the Japanese Nation. Kato provides one listing of the 30 kami coming from the Jingishōjū 神祇省.

- Kokugakuin University, Encyclopedia of Shinto, Hokke Shintō Entry //// Sanjūbanshin Entry

- List of the Thirty Tutelaries Protecting the Naishidokoro 内侍所 (inner sanctum of imperial palace, the location of the sacred mirror). In Japanese only. This site also sells carvings of the 30 kami.

- Rosenfield, John M. Portraits of Chōgen: The Transformation of Buddhist Art in Early Medieval Japan (Japanese Visual Culture). Brill Academic Pub (2010/11). Hardcover. ISBN 9789004168640. See page 214 (Note 28, Kehi), page 219 (Note 80, Kibitsu), page 220 (Note 88, Kitano).

- Saeki, Eriko 佐伯 英里子. Reconsideration of paintings of Sanjūban-shin (set of thirty shinto deities): an introduction of Shirahige Shrine version 三十番神絵像再考--白髭神社所蔵本の紹介を兼ねて. Vol. 294, Ars Buddhica 仏教芸術, 2007 (Sept.), pp. 33-45; Ars Buddhica is a journal published by Mainichi Shimbun 毎日新聞社. Also see another article by Saeki Eriko entitled Notes on the Sanjūbanshin in the Collection of the Honma Museum of Art 三十番神絵像小考(3)本間美術館所蔵作品を中心に, Ars buddhica (276), 35-51,6, 2004-09.

- Songs to make the dust dance: the Ryōjin hishō of twelfth-century Japan. By Yung-Hee Kim. University of California Press, 1994. This resource described many of the kami listed in Table One above.

- Tobibudo List of All 30 Kami, with individual pages for each; plus images and sanskrit seeds from the Butsuzo-zu-i.

OTHER SANJŪBANJIN ARTWORK

- Panel painting of Sanjuubanshin 板絵著色三十番神像, dated 1433, at Shirahige Jinja Shrine 白髭神社, Moriyama 守山, Shiga Prefecture. Made from one piece of cedar. Shows 30 kami sitting in six-column, five-row format. Unable to find photo.

Oldest existing example of a complete representation of the thirty kami is a painting kept at Myōmanji Temple 妙満寺 (Kyoto ??), consecrated with the kaō (signature) of Nichiren monk Kuonjōin Nisshin 久遠成院 日親 (1406-1488). <source Lucia DolceREFERENCES:

Dolce, Lucia (2003) Hokke Shinto. Kami in the Nichiren Tradition. In: Teeuwen, M. and Rambelli, F., (eds.), Buddhas and Kami in Japan. Honji Suijaku as a Combinatory Paradigm. Curzon Routledge, pp. 229, footnote 20. >

- Myōhōji Temple 妙法寺 (Nichiren) in Osaka. Wooden statues of the 30 kami, 10 female rasetsu, and Kariteimo inside the Banjidō 番神堂 (special structure for the 30 kami). The temple holds an annual event on Sept. 15 to venerate this group of deities. Age of statues not listed. Actually, there are now 31 deities to reflect the introduction of the solar calendar and its 31-day month. The new deity is Goban Zenshin 伍番善神.

- Jōshōji Temple 常照寺 (Hyōgo) set of 30 wood statues.

- Mandala of the Lotus depicting Kishimojin at the centre and the sanjūbanjin at the bottom of the icon (colour on silk, 109.3 × 53.8 cm). Dated 1511 (Eishō 8), it bears the kaō of Hōshōin Nichijun (?-1521). The painting is owned by Jitsujōji Temple 實成寺, Aichi Prefecture, and is kept at Nagoya Municipal Museum 名古屋市美術館.

- Honma Mandala 本間曼荼羅, kept at the Honma Museum of Art 本間美術館 in Yamanashi. It depicts the 30 kami with the seed letters of their honji. <source: Dolce, p. 248>

|

|

|

|