|

|

|

|

Shrines by Type, Shrines by Kami (Deity) Shrines by Type, Shrines by Kami (Deity)

Japan is home to some 90,000 Shintō shrines. These are classified into a bewildering number of schools and sects by academics, historians, the government, and believers. Despite great confusion in classification schemes, only a limited number of shrine types enjoy nationwide popularity. These popular shrines often have old and modern names, as many were forced to change their names during the government’s forced separation of Shintō and Buddhism in Japan’s Meiji Period (1868-1912). Names can also vary among Japanese localities and regions, thus causing more confusion.

Shrine Classifications

- Jinja Shintō (Shrine Shintō). The most prevalent. Details here.

- Koshitsu Shintō (Imperial House Shintō, State Shintō, Jingū Shintō). Details here.

- Minzoku Shintō (Folk Shintō). Details here.

- Shūha Shintō (Sect Shintō, Sectarian Shintō). Details here.

- New Religions. Details here.

Predominant Shrine Types

- Asama Shrines 浅間 (Mt. Fuji, Easy Childbirth)

- Benzaiten Shrines 弁財天 (Wealth, Art, Literature, Water)

- Daikoku - Ebisu Shrines 大黒 & 恵比寿 (Wealth, Prosperity)

- Ebisu - Daikoku Shrines 大黒 & 恵比寿 (Wealth, Prosperity)

- Gion Shrines (Protect People Against Evil & Epidemics)

- Goryō Shrines 御霊神社 (Appease Dead Souls & Angry Spirits)

- Hachiman Shrines 八幡宮 (Warriors, Archery)

- Hakusan Shrines 白山神社 (Mountain worship, ascetic practices)

- Hie Shrines 日吉 (Monkey, Happy Marriage, Kids, Syncretism)

- Hitohira Shrines 琴平 (Seafaring, Fishing, Water)

- Inari Shrines 稲荷 (Rice, Fox, Agriculture)

- Ise Shrines 伊勢神宮 (State Shintō, Amaterasu)

- Izumo Taisha 出雲大社 (Happy Marriage, Medicine)

- Jingū Shrines (State Shintō, Amaterasu)

- Kasuga Shrines 春日大社 (Fujiwara Clan; Syncretism)

- Komagata Shrines 駒形 (Devoted to the gods and goddesses of horses)

- Konpira Shrines 金比羅 (Seafaring, Navigation, Fishing)

- Kotohira Shrines 金刀比羅宮 (Seafaring, Fishing, Water)

- Kumano Sanzan 熊野三山 (Syncretism, Sacred Mountains)

- Mikumari Myōjin Shrines 子守明神 (Water distributiion, rain, children)

- Munakata Shrines 宗像 (Safety at sea, bountiful fishing, island and water kami)

- Sengen Shrines 浅間 (Children, Easy Childbirth)

- Shirahata Shrines 白旗 (Genji clan, Minamoto clan, warriors, war)

- Shirayama Shrines 白山神社 (Mountain worship, ascetic practices, syncretism)

- Shugendō Sites (Mt. Ōmine region, ascetic practices)

- Sōja Shrines 総社 (Consolidated, multiple deities)

- Suitengū Shrines 水天宮 (Water, Fertility)

- Sumiyoshi Shrines 住吉 (Hachiman, Wars on the Sea, Sailors)

- Tendai Sannō Shrines 天台山王 (Monkey, Fertility, Syncretism)

- Tenjin Shrines 天神 (Deified People)

- Ujigami Shrines 氏神 (Clan Specific)

- Yakumo (Yagumo) Shrines 八雲神社 (Health, Sickness, Epidemics)

- Yasaka Shrines 八坂神社 (Health, Sickness, Epidemics)

- Yasukuni Shrine 靖國神社 (War Dead)

Above list is not comprehensive. For another list,

see Kokugakuin University Encyclopedia of Shintō.

Asama Shrines 浅間神社. Also pronounced Sengen Shrines. These shrines are dedicated to the mythical princess Konohana Sakuya Hime (木花之佐久夜毘売; also spelled Konohanasakuyahime), the Shintō deity of Mount Fuji and of cherry trees in bloom. She is also known as Koyasu-sama 子安様, a Shintō deity who grants easy childbirth. But after Buddhism gained a strong foothold in Japan, Koyasu-sama was supplanted by her Buddhist equivalents, known as Koyasu Kannon, Jibo Kannon, Koyasu Jizo, Koyasu Kishibojin, and Maria Kannon (a Christian-related form). For more deities of motherhood, please see Guardians of Children. Over 1,000 Asama (Sengen) shrines exist across Japan, with the head shrines standing at the foot and the summit of Mount Fuji itself. Asama Shrines 浅間神社. Also pronounced Sengen Shrines. These shrines are dedicated to the mythical princess Konohana Sakuya Hime (木花之佐久夜毘売; also spelled Konohanasakuyahime), the Shintō deity of Mount Fuji and of cherry trees in bloom. She is also known as Koyasu-sama 子安様, a Shintō deity who grants easy childbirth. But after Buddhism gained a strong foothold in Japan, Koyasu-sama was supplanted by her Buddhist equivalents, known as Koyasu Kannon, Jibo Kannon, Koyasu Jizo, Koyasu Kishibojin, and Maria Kannon (a Christian-related form). For more deities of motherhood, please see Guardians of Children. Over 1,000 Asama (Sengen) shrines exist across Japan, with the head shrines standing at the foot and the summit of Mount Fuji itself.

In Shintō mythology, Konohana (lit = tree flower) is the daughter of Ōyamatsumi (the earthly kami of mountains). She was married to Ninigi 邇邇芸尊 (heavenly grandchild of sun goddess Amaterasu), became pregnant in a single night, and gave birth to three children while engulfed in fire. In some accounts she died in the fire, and thus she is likened to the short-lived beauty of the cherry blossom. But in other accounts, she survived the fire. She is also known as Konohana Sakuya Hime no Mikoto, Kamuatatsu Hime, Kamu Toyoatatsu Hime, and Kamu Atakaashitsu Hime. One of her children, Hōri no Mikoto 火遠理命, married the Dragon King’s daughter, who then gave birth to Jinmu Tennō 神武天皇, Japan’s legendary first emperor. Learn more about this mythical princess at the Encyclopedia of Shintō (Kokugakuin Unniversity). Also see this link (J-site) for more on Asama Shrine.

Benten, Benzai, or Benzaiten Shrines / Temples

弁天 | 弁財天 | 弁才天. Japan’s preeminent goddess of water, one who is worshipped independently or as one of Japan’s Seven Lucky Gods at thousands of Shintō, Buddhist, and Shugendō sites around the country. Her temples and shrines are, befittingly, nearly always in the neighborhood of water -- the sea, a river, a lake, or a pond. This deity originated in India as a Hindu river goddess and was later adopted (8th century CE) into Japan's pantheon of divinities. Sarasvatī, her Sanskrit name, means "flowing female" and thus she represents everything that flows (e.g., music, words, speech, eloquence). Sarasvatī was invoked in Vedic rites as the deity of music and poetry well before the emergence of Buddhism in the 5th century BCE. Benzaiten is also one of many Tenbu (天部 celestial beings; known as DEVA in Sanskrit), and among the top goddesses in a group known as the Tennyo 天女 (celestial maidens). She comes in many forms in Japan, but the three most prominent are (1) a two-armed beauty playing a four-stringed lute; in this form she is known as Myō-on Ten; (2) with eight arms holding martial implements to indicate her role as protector of the nation; in this form, she is known as Happi Benzaiten; and (3) with a human-headed white snake and shrine gate atop her head; in this form, she is known as Uga Benzaiten. She serves numerous roles, including goddess of learning, oral eloquence, performing arts, wealth, longevity, national defense, battlefield success, and one who can end droughts and bring rain. Most importantly, she is the predominant muse of Japanese art, one who inspires musicians, writers, poets, lovers, and artists in all professions. From a modern perspective, the realms of imagination and Jungian unconscious are often compared to deep uncharted waters from which spring life-renewing creative forces and artistic inspiration. Benzaiten's traditional links with flowing water and artist endeavor are therefore most appropriate -- even from a modern psychological standpoint. She is also a patron of motherhood, and is associated closely with the snake and dragon -- both creatures of water and members of the naga family. On days of importance to the serpent in Japan, one can find many festivals at the numerous Japanese shrines and temples dedicated to Benzaiten, in which votive pictures with serpents drawn on them are offered. It is also said that putting a cast-off snake skin in your purse/wallet will bring you wealth and property. During the Kamakura Period, artists for the first time began to create "naked" sculptures of Buddhist and Shintō deities (see above photo). The object of their artistic talents was often Benzaiten, although other deities, like Jizō Bosatsu, were also sculpted in the nude. One of her main sanctuaries is on the island of Enoshima (江の島) in Sagami Bay, about 50 kilometers south of Tokyo, where she and a dragon are the central figures of the Enoshima Engi (江嶋縁起), a history of the shrines on Enoshima written by the Japanese Buddhist monk Kokei 皇慶 in 1047 A.D. Among the myriad sanctuaries devoted to her, the three most widely known are those at Enoshima 江ノ島 (near Kamakura), Itsukushima 厳島 (Miyajima Shrine, Hiroshima), and Chikubushima 竹生島 (Chikubushima Shrine, Lake Biwa, Shiga Prefecture) -- all islands. The three are collectively known as the Three Great Benten Shrines (Nihon Sandai Benten 日本三大弁天). For more details on Benzaiten, click here.

Daikoku & Ebisu Shrines 大黒 and 恵比寿. Daikoku and Ebisu are two of Japan's most popular deities. Daikoku (of Hindu origin) is the god of the earth, agricultural, rice, and wealth. Ebisu (of Japanese origin) is the god of the sea, fishing folk, and prosperity. Both are members of Japan's Seven Lucky Gods. The two are often paired together as an intimate set, and artwork of the pair can be found everywhere in Japan. Many shrines and temples have small enclaves within their precincts that are devoted to the pair. Ebisu has a large following in the Osaka area. For example, the Imamiya-Ebisu Shrine 今宮恵比寿神社 in Osaka holds the "Toka Ebisu Festival" each year on January 9, 10, and 11. During the festivities, says the Flammarion Iconographic Guide to Buddhism (page 239), “business people strike the walls of his sanctuary with mallets to call him, because he is believed to be rather deaf. Large radishes (daikon) steeped in vinegar are offered to him as tributes.”

Other shrines nationwide hold the same festival as well, such as the Toka Ebisu Shrine 十日恵比須神社 in Fukuoka City (Fukuoka Prefecture). Nishinomiya Shrine 西宮神社 (Hyōgo Prefecture) is another popular Ebisu site and it attracts many pilgrims. Click here (outside link) to learn more about the Toka Ebisu Festival.

Gion Shrines 祇園. See Yasaka Shrines.

Goryō Shrines 御霊神社 (Ancestor Worship, Dead Spirits). Goryō literally means “honorable soul.” Such shrines are located throughout the Japanese islands, and are devoted to appeasing and venerating the souls of departed people -- those who died unnaturally, by violence, in a state of anger or resentment. Their souls are enshrined at numerous nationwide Goryō Shrines to avoid their anger and malevolence. Most of these shrines hold regular services to pacify the spirits of the dead and to exorcise evil attachments. Representative examples are the Kami Goryō Jinja 上御霊神社 in Kyoto and the Shimo Goryō Jinja 下御霊神社, also in Kyoto. A list of well-known shrines in this group can be found here (J-site).

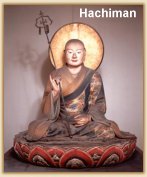

Hachimangū Shrines 八幡宮. Hachimangu Shrines worship the 15th Emperor, Ōjin 応神, who was long ago deified as the god Hachiman 八幡 (lit. “eight banners” which supposedly fell from heaven in legends involving Ōjin). These shrines typically deify three figures -- Emperor Ōjin, his mother Empress Jingu 神功, and Ōjin’s wife Himegami 比売神. In the late 6th century, the Hachiman cult was based at Usa Hachimangū 宇佐八幡宮 shrine in Ōita Prefecture, with the deity playing an oracular function and exhibiting attributes of both Shintō animism and Korean shamanism. It was only later, sometime in the 9th century, that the deity became associated with Emperor Ōjin, and later still that Hachiman became worshipped as the god of archery and war, ultimately becoming the tutelary deity of the Minamoto clan and famed warrior Minamoto Yoritomo 源頼朝 (1147-1199), founder of the Kamakura shogunate. Hachiman is also considered a Bodhisattva, and thus serves as protector in both Shintō and Buddhist traditions. The Tsurugaoka Hachimangū Shrine in Kamakura ranks among the most prestigious shrines in Japan. There are approximately 30,000 Hachimangu shrines nationwide, with the head shrine at Usa Hachimangu in Ōita Prefecture. For more on Hachiman lore, plus details and photos, click here. Hachimangū Shrines 八幡宮. Hachimangu Shrines worship the 15th Emperor, Ōjin 応神, who was long ago deified as the god Hachiman 八幡 (lit. “eight banners” which supposedly fell from heaven in legends involving Ōjin). These shrines typically deify three figures -- Emperor Ōjin, his mother Empress Jingu 神功, and Ōjin’s wife Himegami 比売神. In the late 6th century, the Hachiman cult was based at Usa Hachimangū 宇佐八幡宮 shrine in Ōita Prefecture, with the deity playing an oracular function and exhibiting attributes of both Shintō animism and Korean shamanism. It was only later, sometime in the 9th century, that the deity became associated with Emperor Ōjin, and later still that Hachiman became worshipped as the god of archery and war, ultimately becoming the tutelary deity of the Minamoto clan and famed warrior Minamoto Yoritomo 源頼朝 (1147-1199), founder of the Kamakura shogunate. Hachiman is also considered a Bodhisattva, and thus serves as protector in both Shintō and Buddhist traditions. The Tsurugaoka Hachimangū Shrine in Kamakura ranks among the most prestigious shrines in Japan. There are approximately 30,000 Hachimangu shrines nationwide, with the head shrine at Usa Hachimangu in Ōita Prefecture. For more on Hachiman lore, plus details and photos, click here.

Hakusan Shrines. See Shirayama Shrines below. Also see Sacred Hakusan Mountains.

Hie Jinja Shrines 日吉神社 or 日吉大社 Hie Jinja Shrines 日吉神社 or 日吉大社

Hie Shrines are dedicated to Sannō 山王, the guardian deity of Mt. Hiei 比叡 in Shiga Prefecture (near Kyoto). Sannō 山王 (literally “Mountain King”) is the central deity of Japan's Tendai Shinto-Buddhist multiplex on Mt. Hiei. The monkey is Sannō's messenger (tsukai 使い) and avatar (gongen 権現). Monkeys are considered patrons of harmonious marriage and safe childbirth at most of the 3,800 Hiei Jinja 日吉神社 shrines in Japan, which are located in close proximity to Tendai temples. The name SANNŌ was given to the original Japanese Shintō mountain kami 神 Ōyamagui 大山咋 (or Oyamakui) by the Japanese monk Saichō 最澄 (766-822 AD), the founder of Japan’s Tendai sect. Saichō had studied the teachings in China, and the name he gave the kami probably came from the Chinese god who protected Mount Tientai 天台 in China (Mt. Tientai, Zhejiang Province, China). Read the legend of how Saichō chose the name Sannō.

Photo: Monkey Guarding the Gate at Hie Jinja (Hie Shrine), Akasaka, Tokyo, Japan. Photo by James Baquet. The female monkey shown here cradles a baby in her arms and is considered the patron of harmonious marriage and safe childbirth. For more details, please see the Monkey Page. Also see Patrons of Motherhood and Children.

Hie Shrines are part of Hie Shintō 日吉神道 <see also Tendai Shintō and Sannō Ichijitsu Shintō>, a syncretic school that combined Shintō beliefs with the teachings of Tendai Buddhism. The Tendai sect’s central temple-shrine multiplex is located at the base of (and around) Mt. Hiei. The main temple is Enryakuji Temple 延暦寺, with Hie Jinja 日吉神社 (aka Hiyoshi Taisha 日吉大社, aka Sannō Gongen 山王権現) serving as the main tutelary shrine. The Tendai sect gained great favor and influence in court affairs in the Heian period (794 to 1185), and played a major role in the syncretic merging of Shintō and Buddhism. The Sannō deity, for example, is broadly conceived, for Sannō actually represents three Buddhas (Shaka, Yakushi, and Amida), who in turn represent the three most important Shintō kami of Hie Jinja (Hie Shrine). These three kami are Ōmiya 大宮, Ninomiya 二宮, and Shōshinshi 聖真子. These manifestations of Sannō are called "Hie Sannō Gongen" (日吉山王権現 Mountain King Avatars of Hie Shrine). The ideograms for Sannō 山王 (山 = mountain, 王 = king) both reflect the syncretism of the Tendai tradition and the importance of the number three to Tendai followers. The home of China's Tientai (Jp. = Tendai) sect was on Mt. Tientai (天台山, literally "heavenly terraced mountain"). This name, moreover, is attributed to the mountain's location below a three-star constellation north of the Big Dipper in Ursa Major. The three stars are known as the Three Terraces or Three Platforms (三台, Jp. = Sandai), and were considered a symbolic staircase connecting heaven to the earth. The overwhelming predominance of the number three in Tendai circles is probably, therefore, the origin of Japan's three-monkey symbolism (see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil). An interesting legend describes how Saichō chose the name Sannō. Read the legend.

There are a total of 21 shrines at Mt. Hiei, known as the “21 Sannō Group” (Sannō Nijuuissha 山王二十一社). These 21 shrines are split into three groups of seven -- the three groupings represent the three main Buddha/Kami of the Tendai complex, who are Shaka (Ōmiya 大宮), Yakushi (Ninomiya 二宮), and Amida (Shōshinshi 聖真子). The so-called Upper Seven Sannō Shrines (Sannō Kami no Shichisha 山王上七社) form the core of the Sannō complex. They are associated with Shaka (the Historical Buddha) and the Shintō deity Ōnamuchi no Kami 大己貴神 (agricultural deity; also known as Ōkuninushi no Mikoto 大国主命 or Ōbie no Kami 大比叡神; also read Ōhiegami). The seven are known as the Big Hiei Group and are identified with the seven stars of the Big Dipper (Hokuto Shichisei 北斗七星). The next group of seven shrines, known as the Little Hiei Group, is associated with Yakushi Buddha (the Medicine Buddha) and the Shintō kami Ōyamagui no Kami 大山咋 (mountain kami; the kami of brewing; the original presence or Jinushigami 地主神; also called Kobie no Kami 小比叡神; also read Kohiegami). Both Ōnamuchi and Ōyamagui are mentioned in Japan’s oldest surviving text, the Kojiki 古事記 (712 AD; Record of Ancient Matters).

The shrine buildings are located at the base of Mt. Hiei and at the foot of a small hill called Hachiōjisan 八王子山 (which is the multiplex’s most sacred mountain or its Shintaizan 神体山). The mountain kami Hachiōji 八王子 is identified with the Buddhist deity called the 1000-armed Kannon. Sannō is likewise identified with Amaterasu Ōmikami 天照大神, the supreme goddess of Japan’s native Shintō tradition, from which the imperial family claims its lineage. The Tōshōgū Shrine 東照宮 at Nikkō 日光 is another famous site associated with Tendai Shintō and the three monkies (hear, see, speak no evil). The Tendai Buddhist sect played a major role in the merger of Shintō and Buddhist deities and philosophies. The Hie Sannō Mandala is an important artistic representation of this syncretism. Finally, the Sannō Festival 山王まつり is one of Japan's big three Shintō festivals (typically held in mid-June in central Tokyo). For photos of the festival, click here (outside link).

Learn More about Hie Shrines:

Hitohira Shrines 琴平. See Kotohira Shrines.

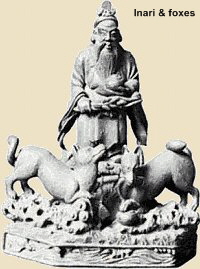

Inari Shrines 稲荷. Inari (also called Oinari or Oinari-sama) is the Japanese god/goddess of rice cultivation, the five grains, and the harvest. The deity’s name translates as “rice cargo.” Inari is popularly associated with the kitsune (fox) deity, said to be Inari's messenger. Inari is also commonly identified with Uka no Mitama no Kami 宇迦之御魂神, the Shintō patron deity of agriculture and grain. Inari lore is quite complex and confusing, and some think the deity represents a hybrid Shintō-Buddhist divinity. Characteristics of Inari shrines are vermilion torii 鳥居 (gates) protected by a pair of fox statues, one on the left, and one on the right. There are some 30,000 Inari shrines nationwide. Curiously, most Japanese no longer distinguish between the god (Inari) and the messenger (fox or kitsune) -- for all practical purposes, the two have been amalgamated into one. The first and oldest Inari shrine is Fushimi Inari Taisha 伏見稲荷大社 (in Kyoto), which dates back to 711 AD. It is the headquarters of all Inari shrines in Japan, and enshrines the spirit of Uka no Mitama. It is an impressive shrine, for visitors must pass through more than 10,000 vermilion torii to reach the inner sanctuary. Fushimi Inari Taisha is also one of Japan’s most popular shrines. It attracts some 2.5 million visitors during the first three days of the New Year holiday. See Fushimi Inari’s homepage (J-site). Inari Shrines 稲荷. Inari (also called Oinari or Oinari-sama) is the Japanese god/goddess of rice cultivation, the five grains, and the harvest. The deity’s name translates as “rice cargo.” Inari is popularly associated with the kitsune (fox) deity, said to be Inari's messenger. Inari is also commonly identified with Uka no Mitama no Kami 宇迦之御魂神, the Shintō patron deity of agriculture and grain. Inari lore is quite complex and confusing, and some think the deity represents a hybrid Shintō-Buddhist divinity. Characteristics of Inari shrines are vermilion torii 鳥居 (gates) protected by a pair of fox statues, one on the left, and one on the right. There are some 30,000 Inari shrines nationwide. Curiously, most Japanese no longer distinguish between the god (Inari) and the messenger (fox or kitsune) -- for all practical purposes, the two have been amalgamated into one. The first and oldest Inari shrine is Fushimi Inari Taisha 伏見稲荷大社 (in Kyoto), which dates back to 711 AD. It is the headquarters of all Inari shrines in Japan, and enshrines the spirit of Uka no Mitama. It is an impressive shrine, for visitors must pass through more than 10,000 vermilion torii to reach the inner sanctuary. Fushimi Inari Taisha is also one of Japan’s most popular shrines. It attracts some 2.5 million visitors during the first three days of the New Year holiday. See Fushimi Inari’s homepage (J-site).

Ise Jingū 伊勢神宮. The Grand Shrine of Ise (or Ise Shrine) in Mie Prefecture continues to play a pivotal role in modern-day Shintōism. It and its numerous sub-shrines are devoted to Amaterasu Ōmikami 天照大神 (female, sun goddess, chief deity of Ise's inner sanctuary or Naikū 内宮) and Toyōke Ōmikami 豊受大御神 (male, god of agriculture and industry, chief deity of Ise's outer sanctuary or Gekū 外宮). The high priest and high priestess of Ise Shrine are typically members or descendants of Japan’s imperial family. The worship of Amaterasu is of particular importance, for Japan’s imperial family claims direct descent from her divine lineage. Ise Shrine is arguably one of Japan’s most important Shintō enclaves and one of the nation’s oldest. See Kōshitsu Shintō for more on Ise Shintō 伊勢神道. Also see <Ise Mandala> <Ise Sankei Mandara> <Sengū: Changing of the Shrine>

Ise Related Topic = Okage Mairi お蔭参り. Special pilgrimages to the Grand Shrines of Ise made every 60 years, in the "Okage” year (the “thanksgiving” year). Pilgrimages to the Ise Shrines originated in the late Kamakura period (1185-1332 AD), when the common folk began group pilgrimages to Ise in the hope of gaining the blessings of the shrines’ divinities. The 60-year pilgrimage tradition, however, reportedly originated later, in the Edo Period. Sixty years, incidentally, represents the 60-year cycle of the Zodiac. In these bygone days, when people were not allowed to travel freely, people impulsively set out to visit Ise without permission from family or employers or without obtaining permission from authorities. Even today, many Japanese dream of visiting the Grand Shrines of Ise at least once in their life.

Izumo Taisha 出雲大社. The Grand Shrine of Izumo (Izumo Taisha) in Shimane Prefecture is one of Japan’s oldest shrines. It is devoted to Ōkuninushi 大国主命, the Shintō kami of abundance, medicine, luck, and happy marriages. In Japanese mythology, Ōkuninushi (lit. = Master of the Great Land) built and ruled the world until the arrival of Amaterasu’s grandson, Ninigi-no-Mikoto 瓊瓊杵尊. He then gave political control to Ninigi but retained control of religious affairs. In gratitude, Amaterasu presented Ōkuninushi with the Grand Shrine of Izumo. According to Japanese tradition, all Shintō gods meet in Izumo each year in October. October is thus known around Izumo as Kamiarizuki 神有月 (Month with Gods) and everywhere else in Japan as Kannazuki 神無月 (Month Without Gods). Ōkuninushi’s Buddhist counterpart is Daikokuten (the god of agriculture and fortune, and one of Japan's Seven Lucky Gods). In addition, Izumo no Okuni 出雲の阿国, the so-called founder of Japanese Kabuki 歌舞伎 theatre, was a shrine virgin (miko 巫子) of Izumo Taisha 出雲大社. She was the subject of a painting genre that flourished in the 17th century known as Fūzokuga 風俗画, and is credited with a devotional dance called Nembutsu Odori 念仏踊り. For more details about her, see John Dougill's Izumo no Okuni: Kagura to Kabuki. For more details on Izumo, see Izumo: The myths and gods of Japan's history, story by Sachiko Tamashige, Japan Times, 16 August 2012.

Jingū 神宮 shrines are associated with the imperial family and are typically devoted to the sun goddess Amaterasu, for Japan’s imperial family claims direct descent from her lineage. Jingū shrines also serve to commemorate the souls of Japan’s former emperors and empresses. Also known as Imperial House Shintō, State Shintō, or Koshitsu Shintō. Notable shrines are Ise Jingū 伊勢神宮 in Ise and Atsuta Jingū 熱田神宮 in Nagoya (both dedicated to the Shinto Sun Goddess Amaterasu). Jingū shrines were directly funded and administered by the government during the era of State Shintō (from the start of the Meiji Era to the end of WWII), and include a number of shrines built during the Meiji restoration, such as Tokyo's Meiji Shrine 明治神宮 and Kyoto's Heian Shrine 平安神宮. Jingū 神宮 shrines are associated with the imperial family and are typically devoted to the sun goddess Amaterasu, for Japan’s imperial family claims direct descent from her lineage. Jingū shrines also serve to commemorate the souls of Japan’s former emperors and empresses. Also known as Imperial House Shintō, State Shintō, or Koshitsu Shintō. Notable shrines are Ise Jingū 伊勢神宮 in Ise and Atsuta Jingū 熱田神宮 in Nagoya (both dedicated to the Shinto Sun Goddess Amaterasu). Jingū shrines were directly funded and administered by the government during the era of State Shintō (from the start of the Meiji Era to the end of WWII), and include a number of shrines built during the Meiji restoration, such as Tokyo's Meiji Shrine 明治神宮 and Kyoto's Heian Shrine 平安神宮.

Kasuga Shrine 春日大社 (Kasuga Taisha). Says site contributor Gabi Greve: “The Kasuga Shrine, also known as Kasuga Taisha 春日大社, is a Shinto shrine in the city of Nara (Nara Prefecture, Japan). Established in 768 AD and rebuilt several times over the centuries, it is the shrine of the then-powerful Fujiwara 藤原 clan. The interior is famous for its many bronze lanterns, as well as the many stone lanterns that lead up to the shrine. The architectural style (called Kasuga Zukuri 春日造) takes its name from the Kasuga Shrine. The shrine along with the nearby Mt. Kasuga Primeval Forest are registered as a UNESCO World Heritage site (part of the Historic Monuments of Ancient Nara). The enchanting path to Kasuga Shrine passes through Deer Park (where tame deer roam free). Over a thousand stone lanterns line the way.” <end Gabi Greve quote>

|

Kasuga Akadōji

Painting, Dated 1488

H = 73.9 cm, W = 31.5 cm

Treasure of Uetsuki Hachiman Jinja 植槻八幡神社 (in Nara).

|

|

According to legend, a mysterious human figure reportedly appeared on a rock immediately in front of the gate to Kasuga Shrine. Known as Kasuga Akadōji 春日赤童子 (literally "Red Youth"), this deity is often depicted as a youth (Jp. = dōji), colored red (Jp = aka), standing on a rock, and leaning on a staff. In certain poses both in paintings and in prints, Akadōji resembles Kongōdōji 金剛童子, one of the attendants of Fudō Myō-ō 不動明王. His connection with Kasuga is obscure, but he has been identified with Ame-no-Koyane 天児屋根, the Shintō god of the Third Sanctuary there; with Jinushi Gami 地主神 (a Shintō land god with a healer's helping spirit) and with the thunder god of Mount Mikasa 御蓋 (which stands behind the Kasuga Shrine). Extant images date from the Muromachi to Edo periods. The 2,000 Ishidoro (stone lanterns) that line the approach to the Kasuga Shrine are perhaps the most well-known in Japan. They are lighted twice a year, for the lantern festivals held in February and August. According to legend, a mysterious human figure reportedly appeared on a rock immediately in front of the gate to Kasuga Shrine. Known as Kasuga Akadōji 春日赤童子 (literally "Red Youth"), this deity is often depicted as a youth (Jp. = dōji), colored red (Jp = aka), standing on a rock, and leaning on a staff. In certain poses both in paintings and in prints, Akadōji resembles Kongōdōji 金剛童子, one of the attendants of Fudō Myō-ō 不動明王. His connection with Kasuga is obscure, but he has been identified with Ame-no-Koyane 天児屋根, the Shintō god of the Third Sanctuary there; with Jinushi Gami 地主神 (a Shintō land god with a healer's helping spirit) and with the thunder god of Mount Mikasa 御蓋 (which stands behind the Kasuga Shrine). Extant images date from the Muromachi to Edo periods. The 2,000 Ishidoro (stone lanterns) that line the approach to the Kasuga Shrine are perhaps the most well-known in Japan. They are lighted twice a year, for the lantern festivals held in February and August.

Kasuga Shrine is closely aligned with Kōfukuji Temple 興福寺 (also in Nara, a World Heritage site, and one of the Seven Great Temples of Nara). Kōfukuji was founded in +669 by the powerful Fujiwara 藤原 clan and named Yamashinadera 山階寺. It moved twice after that, once to Umayasaka (Nara prefecture) and then again, when the capital was transferred to Heijōkyō 平城京 (today's Nara city), when it was renamed Kōfukuji Temple. It is also sometimes referred to as Kasuga-ji or Kasuga Temple 春日寺, to differentiate it from the Kasuga Shrine. Kōfukuji houses a rich collection of Buddhist art from the Nara era, including statues of the Six Japanese Patriarchs. The temple also served as an important government-run workshop making Buddhist statues in the Nara and Heian periods. The Kasuga Mandala 春日曼荼羅 was another famous art form that sprang from Kasuga Shrine. Such mandala typically include devotional paintings of the deities and landscapes of Kasuga Shrine, but they may also refer to the scenery and deities of Kōfukuji Temple. The Kasuga Matsuri 春日祭 (aka Saru Matsuri 申祭 or Kasuga Monkey Festival) is a popular festival held on the first day of the monkey (saru no hi 申の日) in February and November (old lunar calendar). The Kasuga Shrine was reportedly build in the 2nd year of the Zingo-Keiun era (768). In the Meiji period, the festival date was changed to March 13. During the matsuri (festival), an imperial messenger makes offerings to the Saru (monkey) deity and many Shintō ceremonies are performed. It is one of three great festivals designated by Japan’s imperial court (Sanchokusai 三勅祭).

Komagata (lit. = Horse-shaped) Shrines 駒形. Found throughout Japan, Komagata shrines are devoted to the gods and goddesses of horses, including 宇迦之御魂神 (Ukanomitama no mikoto), 天照大神 (Amaterasu Ōmikami), 天忍穂耳尊 (Ame no oshihomimi), 天之常立神 (Amenotokotachinokami), and numerous other folk deities serving as protectors of horses. Batō Kannon (the Horse-Headed Kannon) is identified as the Buddhist counterpart (honjibutsu 本地仏) of the Komagata deities. The tradition of offering horses to Shintō deities (kami) stretches back to early times, as the kami were believed to ride horses between this world and the sacred realm. Such offerings were beyond the means of the common folk, who instead offered horse-shaped figurines and pictorial votive tablets known as EMA 絵馬 (e = picture, ma = horse), for the votive tablet was often inscribed with the image of a horse. Even today, one can purchase EMA at most shrines in Japan -- on which you write your name and petition, and then hang it within the shrine compound. Iwate was one of Japan’s most famous horse-breeding centers in olden days, and the Komagata Shrine in Iwate Pref. is thus befittingly one of Japan’s most well-known. For more, see John Dougill's White Horse in Shinto Traditions.

Kompira or Konpira Shrines 金比羅神社. See Kotohira Shrines.

|

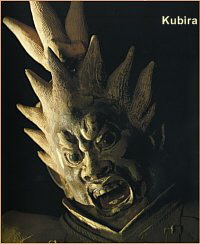

Kubira 宮毘羅

One of the

12 Heavenly Guardians

Clay 塑像 & paint (saishiki 彩色)

H = 165.1 cm standing statue.

Above we present only

a closeup of the face.

Shin-Yakushiji Temple 新薬師持

Nara Era

Photo: Ogawa Kouzou

|

|

Kotohira-gū Shrines 金刀比羅宮. Kotohira shrines can be found throughout Japan. Synonymous with Konpira 金比羅 shrines, Kompira 金比羅 shrines, Hitohira 琴平 shrines, or Kotohira 琴平 shrines. They are devoted to Konpira 金比羅, a local kami 神 (deity) worshipped as the guardian deity for seafarers, navigation, fishing, and water for agriculture. Konpira’s Buddhist counterpart is Kubira 宮毘羅, the leader of Yakushi Buddha's Twelve Heavenly Generals (Jūni Shinshō 十二神将), and also one of the Sixteen Protectors of Shaka Nyorai (Jūroku Zenshin 十六善神). The main shrine is situated on Mt. Zōzusan 象頭山, a maritime location in Kagawa Prefecture (Shikoku Island), where locals fondly call the deity and shrine “Konpira-san” or “Konpira Daigongen” and claim his cult dates back centuries before the introduction of Buddhism to Japan. But, says JAANUS, “According to legend, Konpira flew from India to a sacred cave at Matsuodera Temple 松尾寺 on Mt. Zōzusan 象頭山 (lit. Elephant's Head Mountain), a small mountain near the sea on Shikoku island, and became the temple's protective deity. He is worshipped principally as a seafaring god and secondarily as a god of water for agriculture. He may appear as a snake or as a dragon god (Ryūjin 竜神) and is also identified with Ōmononushi 大物主神, the Shintō kami of Mt. Miwa 三輪, who in turn is identified with Daikokuten (god of agriculture). In the Edo period, Zōzusan was a famous Shugendō 修験道 site (ascetic mountain practices associated with the legendary founder En-no-Gyōja 役行者), and as a result it became a popular Shintō-Buddhist pilgrimage site. In the Meiji period (1868), the site was converted to a Shintō shrine in line with government policies to suppress Shugendō practice and Buddhist faith. The original Matsuodera Temple was therefore renamed Kotohiragū Shrine 金刀比羅宮 and the Konpira deity renamed Ōmononushi no Kami (aka Ōmononushi no Mikoto, aka Ōkuninushi 大国主命, aka Great Land Master). In spite of this, the principal image of the shrine remains that of the Buddhist deity Konpira, who today remains the central deity (shintai 神体) of Kotohiragū Shrine.” <end JAANUS quote>. Kotohira-gū Shrines 金刀比羅宮. Kotohira shrines can be found throughout Japan. Synonymous with Konpira 金比羅 shrines, Kompira 金比羅 shrines, Hitohira 琴平 shrines, or Kotohira 琴平 shrines. They are devoted to Konpira 金比羅, a local kami 神 (deity) worshipped as the guardian deity for seafarers, navigation, fishing, and water for agriculture. Konpira’s Buddhist counterpart is Kubira 宮毘羅, the leader of Yakushi Buddha's Twelve Heavenly Generals (Jūni Shinshō 十二神将), and also one of the Sixteen Protectors of Shaka Nyorai (Jūroku Zenshin 十六善神). The main shrine is situated on Mt. Zōzusan 象頭山, a maritime location in Kagawa Prefecture (Shikoku Island), where locals fondly call the deity and shrine “Konpira-san” or “Konpira Daigongen” and claim his cult dates back centuries before the introduction of Buddhism to Japan. But, says JAANUS, “According to legend, Konpira flew from India to a sacred cave at Matsuodera Temple 松尾寺 on Mt. Zōzusan 象頭山 (lit. Elephant's Head Mountain), a small mountain near the sea on Shikoku island, and became the temple's protective deity. He is worshipped principally as a seafaring god and secondarily as a god of water for agriculture. He may appear as a snake or as a dragon god (Ryūjin 竜神) and is also identified with Ōmononushi 大物主神, the Shintō kami of Mt. Miwa 三輪, who in turn is identified with Daikokuten (god of agriculture). In the Edo period, Zōzusan was a famous Shugendō 修験道 site (ascetic mountain practices associated with the legendary founder En-no-Gyōja 役行者), and as a result it became a popular Shintō-Buddhist pilgrimage site. In the Meiji period (1868), the site was converted to a Shintō shrine in line with government policies to suppress Shugendō practice and Buddhist faith. The original Matsuodera Temple was therefore renamed Kotohiragū Shrine 金刀比羅宮 and the Konpira deity renamed Ōmononushi no Kami (aka Ōmononushi no Mikoto, aka Ōkuninushi 大国主命, aka Great Land Master). In spite of this, the principal image of the shrine remains that of the Buddhist deity Konpira, who today remains the central deity (shintai 神体) of Kotohiragū Shrine.” <end JAANUS quote>.

Kotohiragū Shrine was an important pilgrimage site for Emperor Sutoku 崇徳天皇 (1119 – 1164), the 75th emperor of Japan. It became an especially popular pilgrimage site in the 14th century, and remains very popular even today. The approach requires the pilgrim to climb 785 stone steps to get to the main sanctuary. Mt. Zōzusan, where it is located, is only 531 meters above sea level. But the shrine is only half way up Mt. Zōzusan. Altogether, pilgrims must climb 1,368 stone steps to arrive at the inner shrine. Kotohira is also called Konpira Mōde 金毘羅詣. A statue of the 11-Headed Kannon Bodhisattva (a designated Important Cultural Property) is located inside the shrine precincts.

Kumano Sanzan Shrines 熊野三山. Three famed shrines in Japan’s Kumano region (at the southern tip of Wakayama Prefecture). The Kumano area, moreover, has long been known as the Land of the Kami and the dwelling place (the paradise) of Kannon Bodhisattva. The Kumano shrine complexes played a major role in the syncretic merging of Shintō and Buddhist beliefs and deities. They were likewise influenced by the ascetic practices of Shugendō mountain worship, for Kumano lies at one end of the Ōmine 大峰 mountain range, which is the central site of Shugendō ascetic practice. The Kumano pilgrimage (Kumano Sankeimichi Naka-echi 熊野参詣道中辺路) became popular among all classes of people in the mid-Heian period (794-1192), including the sick, the poor, the imperial family, and nobility. Emperor Shirakawa 白河天皇 (1053 – 1129, Japan's 72nd emperor) made 23 pilgrimages to the site. Today the pilgrimage is still one of Japan’s most popular spiritual routes. Kumano is also reportedly the home of the legendary Tengu goblin (slayer of vanity). People making the Kumano pilgrimage seek salvation based on Sangaku Shinkō 山岳信仰 (belief in the supernatural power of particular mountains) rather than through common religious practice. In terms of artistic output and influence, Kumano is one of the three most important syncretic Shintō-Buddhist sites in Japan, along with the Kasuga 春日 complex in Nara (also see Kasuga Mandala) and the Sannō 山王 temple-shrine multiplex located on Mt. Hiei 比叡 near Kyoto in Shiga Prefecture (also see Hie Sannō Mandala). Paintings known as the Kumano Mandala are among the most famous relics of Shinto-Buddhist syncretism. Kumano Sanzan gained inclusion on the UNESCO World Heritage list in 2004. The three shrines are:

- Kumano Hongū Taisha Honguu 本宮 or Kumano Nimasu Jinja 熊野座神社

Shinto Deity = Ketsu no miko kami 家都御子神; Buddhist Counterpart = Amida (Pure Land)

- Kumano Nachi Taisha 那智 or Kumano Fusumi Jinja 熊野夫須美神社

Shinto Deity = Fusumi 夫須美 or Musubi no kami 結びの神; Buddhist Counterpart = Senju Kannon

- Kumano Shingū Taisha 新宮 or Kumano Hayatama Jinja 熊野速玉神社

Shinto Deity = Hayatama no kami 速玉神; Buddhist counterpart = Yakushi

The three deities of the three shrines (and their Buddhist counterparts) are also known as the Kumano Sansho Gongen 熊野三所権現, to which nine more were added to make a group of twelve called the Kumano Jūnisha Gongen 熊野十二社権現. There are other groupings as well. Says the Chintaku Reifu Engi Shūsetsu 鎮宅霊符縁起集説(1628), as translated on page 221 by Shugendō scholar Gaynor Sekimori in The Worship of Stars in Japanese Religious Practice (edited by Lucia Dolce, special double issue of Culture and Cosmos, ISSN 1368-6534: “According to the writings of En no Gyōja, there are four deities who protect the world. The first dwells in the center of Magadha (a region of ancient India); this is Amida Nyorai, who appears in our land as Chōjō Daibosatsu 頂上大菩薩 (the deity of the Hongū Shrine at Kumano). The second, Hokushin 北辰 (the pole star, literally 'northern dragon'), dwells in the north and is Yakushi Nyorai, manifested in our land as Kumano Gongen. The third is Tayū and the fourth is Hakuta; they are brothers and are Kannon, dwelling at Mount Potalaka. In our land they are called Nachi Gongen 那智権現.” <end quote>

Says JAANUS: It is clear from archaeological discoveries made in sutra mounds that as early as the Nara period (8c), Kumano was the devotional site for the Lotus Sutra (Hokekyō 法華経), for the Paradise of Kannon (Fudarakusen 補陀落山) was said to be located here. In the Heian period, the pilgrimage to Kumano became important to all classes of people, and by the Kamakura and Muromachi periods this was the most popular site in Japan. Part of the attraction was the widespread notion that Japan had entered the Age of Mappo 末法 (Decline of Buddhist Law), when only faith in Pure Land Buddhism and Amida Buddha could bring salvation (click here for details on Mappo and the Three Periods of Dharma Law). From the shore near Kumano Shingū, pilgrims sailed to Kannon's paradise in small unsteerable boats. It was also believed that those who committed suicide at Kumano would go directly to the Paradise of Amida (Gokuraku 極楽). Because Kumano was at one end of the Ōmine 大峰 mountain range, the central site of Shugendō ascetic practise (the other extreme being Yoshino 吉野), it exercised considerable power over the surrounding region, and its warrior monks often played a part in political disputes. Although today the shrines appear entirely Shintō with the exception of Nachi, where Fudarakusanji (Kannon’s paradise) still exists, this purity is the artificial result of the separation of Shintō and Buddism (Shinbutsu Bunri 神仏分離) and the banning of Shugendō in the early Meiji period. <end JAANUS quote>

Mikumari Jinja 水分神社 or Mikomori Jinja 御子守神社 or Mikomori Myōjin 御子守明神. Mikumari 水分 literally means “water-dividing kami,” which refers to deities who control the allocation of running water. There are numerous kami in this category. Says the Encyclopedia of Shinto: “Amatsumikumari no kami 天津水分神 (Heavenly Mikumari) and Kunitsumikumari no kami 国津水分神 (Earthly Mikumari). Shrines devoted to these two kami as objects of worship (saijin 祭神) can be found in numerous locales, but the best known would include the shrines Katsuragi Mikumari Jinja, Yoshino Mikumari Jinja, Uda Mikumari Jinja, and Tsuge Jinja (all in Nara Prefecture); and the Take Mikumari Jinja and Ame no Mikumari Toyo-ura Mikoto Jinja (Osaka)......such kami are also the object of worship in rites invoking rain (amagoi 雨乞い).” <end quote> Says JAANUS. “Also called Komori Myōjin 子守明神, a female deity who may appear in a triad known as Mikomori Sannyoshin 御子守三女神. This female deity of the shrine Yoshino Mikumari Jinja 吉野水分神社 is situated on a ridge above the village of Yoshino 吉野 in southern Nara. It is one of four major watershed shrines in old Yamato 大和 (i.e., Japan). Yoshino Mikumari appears in a record of 702 and was known as a site at which to pray for control of rain and water. Apparently through a misapprehension of the sound, Mikumari became known as Mikomori, a protector of children. Mikomori is one of the eight gongen 権現 of Yoshino, gongen being the forms taken by supernatural beings in order to manifest themselves on earth. There are twenty sculptures of the deity at Yoshino Mikumari Jinja. The most famous of these is that of Tamayorihime 玉依姫, dating from 1251. She appears in the KOJIKI 古事記 (712) as the mother of Emperor Jinmu (Jimmu) 神武. In this case she appears accompanied by two other deities and the three together are known as the Mikomori Sannyoshin. It is important to note that Tamayorihime is not identical with Mikomori Myōjin, since the latter is the collective deity of the whole shrine and includes a number of other deities. In paintings Mikomori may appear alone or in a triad. She is shown as a court lady, and she may be with children or shown holding a vajra (a symbol/weapon often held by Buddhist deities to represent their power to overcome evil). She and/or her shrine often appear in Yoshino Mandala 吉野曼荼羅. Mikomori Myōjin's Buddhist counterpart (honjibutsu 本地仏) is Jizō Bodhisattva 地蔵, and the bonji 梵字 (Siddham letter or mystical sound of the deity) for Dainichi Buddha 大日 of the Taizōkai Mandala 胎蔵界曼荼羅 may appear on paintings of her.” <end JAANUS quote>

SOURCES (last accessed on Dec. 3, 2011)

|

|

In the 8th and 9th centuries, Japanese envoys to Korea

and to China (kentōshi 遣唐使) visited Munakata Taisha

before their departure to pray for safety on the sea

voyage. In the Nihongi, the supreme sun goddess

Amaterasu commands the Munakata goddesses to protect

the sea route from northern Kyushu to the Korean Peninsula.

|

|

Munakata Shrines 宗像 and Munakata Taisha 宗像大社. Munakata Taisha in Munakata City (Fukuoka) is the mother shrine for some 6,000 satellite Munakata shrines nationwide. Munakata shrines are dedicated to the Munakata Sanjoshin 宗像三女神 (also written 胸形三女神), the “Three Female Kami of Munakata.” These three are water goddesses, island kami, patrons of safety at sea, bountiful fishing, guardians of the nation, protectors of the imperial household. The trio appear in the Kojiki 古事記 (K) and Nihon Shoki 日本書紀 (NS), two of Japan's earliest official records of the 8th century, although the spelling of their names differ slightly. Their worship began under the patronage of the Munakata 宗像 clan on Kyūshū (Kyushu) island, hence they are named the Three Goddesses of Munakata. In the 8th and 9th centuries, Japanese envoys to Korea and China visited Munakata Taisha before their departure to pray for safety on the sea voyage. In the classical texts mentioned above, all three kami were formed when sun goddess Amaterasu broke Susanō's sword, chewed it in her mouth, then blew out a mist that produced the triad <see story>. The three are:

-

|

|

Itsukushima 厳島. The most important

of the Three Munakata Goddesses.

Shown here as she appears in the

1783 version of the Butsuzō-zui.

Click image to see enlarged versions

from both the 1690 and 1783 editions.

She is considered a manifestation of

Benzaiten, Japan’s most preeminent

and popular water goddess. This is

clearly implied in the above image,

where she is shown as a two-

armed beauty playing the biwa --

the exact same iconography used

for Benzaiten’s standard iconic form.

|

|

|

|

|

Ichikishima-hime 市杵嶋姫命 (NS) or Itsukishima-hime 市寸島比売命 (K), or Ichikishima Hime-no-Kami 市杵島姫神, or Sayoribime no Mikoto 狭依毘売命 (K). Enshrined at Hetsumiya (Hetsu-gū ) 辺津宮 in Munakata City, Fukuoka. Also known as Itsukushima Myōjin 厳島明神 at Itsukushima Shrine 厳島神社 (Hiroshima), where she appeared in the late Heian period and was enshrined as the central object of worship and also identified as a manifestation of Benzaiten. Ichikishima-hime is the most important of the three Munakata goddesses. In some shrines she is shown alone yet represents all three.

- Tagitsu-hime 多岐都比売命 (K) or 湍津姫 (NS). Enshrined at Nakatsumiya (Nakatsu-gū) 中津宮 on Ōshima island 大島, roughly ten kilometers from land. In some esoteric traditions, she is considered the goddess of architecture and forestry. <source page 390>

- Tagori-hime 田心姫 (NS) or Tagiri-hime [Takirihime] 多紀理毘売 (K), or 田心姫神. Also known as Okitsushima-hime 奥津島比売命. Her main shrine is Okitsumiya (Okitsu-gū) 沖津宮 on Okinoshima island 沖ノ島 at the southwestern tip of the Sea of Japan. Surprisingly, the island is off limits to women -- a tradition that started early on. In the Kojiki, she marries Ōkuninushi 大国主命 (great landlord kami; identified with Daikokuten, Buddhist deity of agriculture). Tagori-hime has a male manifestation known as Shōshinji Gongen 聖真子権現 (also read Shōshinshi), who is the 19th member of the 30 Kami of 30 Days; he is venerated at Mt. Hiei (the third shrine at Mt. Hiei is Shōshinji 聖真子 or Usamiya 宇佐宮). In some esoteric traditions, Tagori is the kami of agriculture & weaving. <source page 390>.

NOTES

Note 1: In the Encyclopedia of Shinto, Nogami Takahiro says the three goddesses are deifications of female mediums (Ichikishima-hime), rough water (Tagitsu-hime), and fog (Tagori-hime). Last accessed Dec. 2, 2011.

Note 2: Scholar Richard Thornhill provides this illuminating passage: “From ancient times, Benzaiten has been identified with the Shinto goddess of islands, Itsukushima-Hime or Ichikishima-Hime, a minor figure in the oldest Shinto scriptures. In 1870, Shinto and Buddhism were legally separated, and the Shinto clergy have thus stressed this identification so as to continue worshipping Benten at Shinto shrines. In the Rig Veda, Sarasvati is viewed as one of a trinity of goddesses, together with Ila and Bharati or Mahi. In the Shinto classics, Itsukushima-Hime is one of a trinity of water goddesses, together with Tagori-Hime and Tagitsu-Hime, all of whom were formed from the sword of the Sun Goddess Amaterasu.” <end quote by Richard Thornhill> Last accessed Dec. 2, 2011.

SOURCES (all last accessed on Dec. 2, 2011)

Encyclopedia of Shinto: Munakata | Ichikishima-hime | Tagori-hime | Tagitsu-hime

Also see Gabi Greve, Munakata Goddesses

Also see Jean Herbert, Shinto: At the Fountainhead of Japan

Sengen Shrines 浅間神社. See Asama Shrines.

Shirahata Shrines 白旗神社 (Shirahata Jinja). Also written 白幡神社 or 白籏神社. Shrines dedicated to Minamoto Yoritomo 源頼朝 ((1147-1199; founder of the Kamakura Shogunate), his son Minamoto Sanetomo.源実朝 (ruled 1203-1219), and the Minamoto 源 clan (aka Genji 源氏 clan). There are 70+ nationwide shrines, but most are located in the Kantō 関東, Tōhoku 東北, and Chūbu 中部 regions. Says Kondo Takahiro: “The first Shirahata shrine was built in Kamakura by Hōjō Masako 北条 政子 (1156 – 1225) in 1200 AD. Masko was Minamoto’s consort. Shirahata means ’White Flag.’ White was the color of the Minamoto clan's banner. It was dedicated to the memory of Minamoto Yoritomo and Minamoto Sanetomo, but not to their sibling Yoriie 源頼家 (ruled 1202 – 1203). Yoriie was Masako's second son and the second Shogun. Historical records show that he was at odds with his mother.“ <end quote> The Minamoto-Hōjō clan ruled Japan from Kamakura city, and numerous Shirahata sub-shrines can thus be found in the city. Also see Hachimangū Shrines. Hachiman, the Shintō god of archery and war, was the tutelary deity of the Minamoto clan.

Shirayama Shrines 白山. Also known as Hakusan Shrines. Shirayama (also pronounced Hakusan) literally means white mountain, but is actually the collective name for a number of sacred Japanese mountains that converge along the borders of four prefectures (Ishigawa, Fukui, Gifu, and Toyama) in northwest Honshū island. From early on, Hakusan was known as a “mountain realm inhabited by kami” (shintaisan 神体山). The character “shin” 神 is also read “kami,” which means Shintō deity. The mountains were once taboo to climb, but with the subsequent growth of Japan’s Shugendō cult of ascetic mountain practice, Hakusan became a popular site of worship, meditation, pilgrimage, and ascetic training.Today some 2000+ nationwide Shirayama Jinja Shrines 白山神社 (also read Hakusan Shrines) are devoted to this faith. Hakusan is undeniably one of Japan’s most important and ancient sites of religious mountain worship (sangaku shūkyō 山岳宗). The Hakusan mountains are celebrated in the Man'yōshū 万葉集 (Japan’s oldest anthology of verse compiled in the 8th century). Over the centuries, Hakusan became a stronghold of Shintō-Buddhist syncretism, a major pilgrimage site, a center of ascetic practice for the Shugendō 修験道 cult of mountain worship, and the focus of mandala artwork. Today Hakusan is considered one of Japan’s three most sacred mountain sites (Nihon Sanreizan 三霊山 or Nihon Sanmeisan 三名山). The other two are Mt. Fuji and Mt. Tateyama. The Shirayama Hongū Shrine 白山本宮 (aka Hakusan Hongū Shrine) located on Mt. Gozenpō (the highest peak and the most sacred site in the Hakusan region) is the headquarters of all nationwide Shirayama branch shrines-temples. Around 600,000 to 700,000 worshippers visit this central Hakusan shrine every year, which enshrines the Shintō creator god Izanagi and Shintō creator goddess Izanami and the main Shintō deity Shirayama-Hime (aka Kukurihime-no-Kami). The main seven shrines in the Hakusan grouping of 21 shrines are presented below along with their main honji-suijaka (Buddhist-Shintō) counterpart deities. Women are permitted pilgrimage as far as Chūgū. Shirayama Shrines 白山. Also known as Hakusan Shrines. Shirayama (also pronounced Hakusan) literally means white mountain, but is actually the collective name for a number of sacred Japanese mountains that converge along the borders of four prefectures (Ishigawa, Fukui, Gifu, and Toyama) in northwest Honshū island. From early on, Hakusan was known as a “mountain realm inhabited by kami” (shintaisan 神体山). The character “shin” 神 is also read “kami,” which means Shintō deity. The mountains were once taboo to climb, but with the subsequent growth of Japan’s Shugendō cult of ascetic mountain practice, Hakusan became a popular site of worship, meditation, pilgrimage, and ascetic training.Today some 2000+ nationwide Shirayama Jinja Shrines 白山神社 (also read Hakusan Shrines) are devoted to this faith. Hakusan is undeniably one of Japan’s most important and ancient sites of religious mountain worship (sangaku shūkyō 山岳宗). The Hakusan mountains are celebrated in the Man'yōshū 万葉集 (Japan’s oldest anthology of verse compiled in the 8th century). Over the centuries, Hakusan became a stronghold of Shintō-Buddhist syncretism, a major pilgrimage site, a center of ascetic practice for the Shugendō 修験道 cult of mountain worship, and the focus of mandala artwork. Today Hakusan is considered one of Japan’s three most sacred mountain sites (Nihon Sanreizan 三霊山 or Nihon Sanmeisan 三名山). The other two are Mt. Fuji and Mt. Tateyama. The Shirayama Hongū Shrine 白山本宮 (aka Hakusan Hongū Shrine) located on Mt. Gozenpō (the highest peak and the most sacred site in the Hakusan region) is the headquarters of all nationwide Shirayama branch shrines-temples. Around 600,000 to 700,000 worshippers visit this central Hakusan shrine every year, which enshrines the Shintō creator god Izanagi and Shintō creator goddess Izanami and the main Shintō deity Shirayama-Hime (aka Kukurihime-no-Kami). The main seven shrines in the Hakusan grouping of 21 shrines are presented below along with their main honji-suijaka (Buddhist-Shintō) counterpart deities. Women are permitted pilgrimage as far as Chūgū.

Shugendō Sites 修験道. A syncretic sect of Japanese practice that combines Shintō beliefs, pre-Buddhist mountain worship, and ascetic practices with Buddhist teachings in the hopes of achieving mystic powers. The semi-legendary holy man En no Gyoja 役行者 (7th century) is considered the father of Shugendō. Shugendō practice is centered around sacred Mt. Ōmine 大峰山 in Nara (very close to the famed Kumano Sanzan Shrines, another major area of Shinto-Buddhist syncretism). When the Meiji government forcibly separated Shintō and Buddhism (Shinbutsu Bunri 神仏分離) in the late 19th century, the Shugendō sect was declared superstitious and banned by the Meiji government, dealing a severe blow to Shugendō practice. See Sects/Schools page for more on Shugendō, or see the Shugendō page.

Sōja 総社. Also written 惣社. Also pronounced Sōsha or Subeyashiro or Kanjō 勧請. A shrine that contains many deities, which may have individual shrines in distant parts of Japan, thus enabling worshippers easy access to such deities without the necessity of travel. According to some, this custom was originated in the Nara period by a practical-minded provincial governor. He created a consolidated shrine near the provincial capital in order to eliminate the arduous task of visiting all the shrines under his jurisdiction. There were also country and village sōja. <above text courtesy of JAANUS> Another related topic is the Sunafumi お砂踏み Ceremony, or Walking on Sacred Sand. For example, for those unable to make the popular Shikoku pilgrimage to the 88 Sacred Sites, there is a temple in Tokyo’s Setagaya ward called Tamagawa Daishi 玉川大師. Twice each each, the temple holds a special ceremony in May and October, from the 21st to the 23rd, wherein people can pray in front of hanging scrolls of the 88 Temples of the Shikoku Pilgrimage whilst standing on a bag of sacred sand from each respective temple. For much more on this ceremony, which is held at many other Japanese temples associated with Esoteric Buddhism, please visit this outside page by Gabi Greve.

Suitengū Shrines 水天宮 Suitengū Shrines 水天宮

Devoted to the Deity of Water, known as Suijin or Suiten or Mizu no Kamisama. This Shintō deity, often a goddess, protects not only fishermen but also serves as the patron saint of fertility, motherhood, and easy childbirth. She is mostly worshipped at "Suitengū" shrines throughout Japan, and votive stone markers devoted to her can be found frequently in the countryside. The Suitengū Shrine in Kurume (Fukuoka) is the main shrine of all Suitengū Shrines in Japan. It is especially famous to those praying for safe and easy childbirth. For many more details, please visit the Suijin Page. Also see Gabi Greve’s page on Suiten Amulets, Folk Practices/Beliefs, and Easy Delivery.

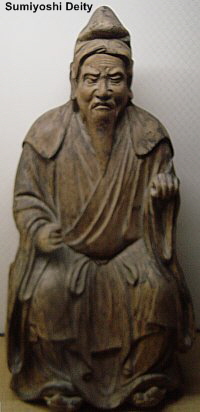

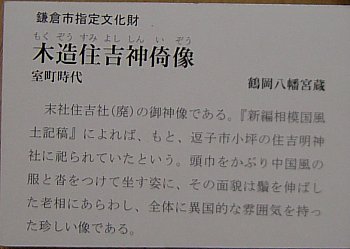

Sumiyoshi Shrines 住吉. These popular shrines are devoted to three deities known as the Sumiyoshi Sanjin 住吉三神. The Osaka-based Sumiyoshi Grand Shrine (Sumiyoshi Taisha 住吉大社) is the central shrine of a nationwide network of 2,300 related shrines, but the oldest is based in Hakata, Japan. Most shrines in the group are devoted to three deities known as Sokotsutsu no Onomikoto 底筒男命, Nakatsutsu no Onomikoto 中筒男命, and Uwatsutsu no Onomikoto 表筒男命. A fourth deity, added in later times, is known as Okinagatarashihime no Mikoto 息長帯日 (aka Empress Jingū 神功皇后). The four are known collectively as the Sumiyoshi Ōkami 住吉大神 (the great gods of Sumiyoshi; also called the Sumiyoshi no Ōgami no Miya 住吉大神宮; also called Sumiyoshi Daijin 住吉大神). The Osaka-based Sumiyoshi Grand Shrine is also considered to be the ancestral origin of Japan's popular Hachiman deity. Hachiman, Japan's god of war, represents Emperor Ōjin (Japan's 15th emperor), who was long ago deified as the god Hachiman to protect warriors on land. His mother (Empress Jingū) was added to the Sumiyoshi triad in later times, and the three (four) are considered gods protecting sailors and those who battle on the sea, while Hachiman represents the god protecting those who battle on land. The term "Sumiyoshi" also refers to an architectural style. Please see below links for more details of architecture and the deity. Sumiyoshi Shrines 住吉. These popular shrines are devoted to three deities known as the Sumiyoshi Sanjin 住吉三神. The Osaka-based Sumiyoshi Grand Shrine (Sumiyoshi Taisha 住吉大社) is the central shrine of a nationwide network of 2,300 related shrines, but the oldest is based in Hakata, Japan. Most shrines in the group are devoted to three deities known as Sokotsutsu no Onomikoto 底筒男命, Nakatsutsu no Onomikoto 中筒男命, and Uwatsutsu no Onomikoto 表筒男命. A fourth deity, added in later times, is known as Okinagatarashihime no Mikoto 息長帯日 (aka Empress Jingū 神功皇后). The four are known collectively as the Sumiyoshi Ōkami 住吉大神 (the great gods of Sumiyoshi; also called the Sumiyoshi no Ōgami no Miya 住吉大神宮; also called Sumiyoshi Daijin 住吉大神). The Osaka-based Sumiyoshi Grand Shrine is also considered to be the ancestral origin of Japan's popular Hachiman deity. Hachiman, Japan's god of war, represents Emperor Ōjin (Japan's 15th emperor), who was long ago deified as the god Hachiman to protect warriors on land. His mother (Empress Jingū) was added to the Sumiyoshi triad in later times, and the three (four) are considered gods protecting sailors and those who battle on the sea, while Hachiman represents the god protecting those who battle on land. The term "Sumiyoshi" also refers to an architectural style. Please see below links for more details of architecture and the deity.

Sumiyoshi Deity, Muromachi Period

Wood, Treasure of Tsurugaoka Hachiman Shrine, Kamakura

Tendai Sannō 天台山王. See Hie Jinja Shrines above.

Tenjin Shrines 天神. Deceased individuals are sometimes deified and thereafter worshipped as Tenjin (lit. "heavenly spirit" or "heavenly god"). Shrines devoted to Michizane Sugawara 菅原道真 (845 - 903 AD) and to Emperor Meiji 明治天皇 (1852 - 1912 AD) are the two most prominent examples of Tenjin shrines. Michizane (courtier in the Heian period, noted poet and academic) was deified after death, for his demise was followed shortly by social unrest in the capital (Kyoto), said to be his revenge for being demoted and exiled to Dazaifu (Kyūshū). Michizane is the patron deity of scholarship, learning, and calligraphy. Every year on the 2nd of January, students go to his shrines to ask for help in the tough school entrance exams or to offer their first calligraphy of the year. Egara Tenjin 荏柄天神 (in Kamakura) is one of the three most revered Tenjin Shrines in Japan, and among the three largest. The other two are Dazaifu Tenmangū 大宰府天満宮 (near Fukuoka; Dazaifu is where Michizane was re-posted after his demotion; it is also where he died), and Kitano Tenjin 北野天神 in Kyoto (Michizane's birthplace). Of a total of about 90,000 Shinto shrines in Japan, there are about 11,000 Tenjin or Tenmangū shrines (editor: must find source of number). Around January 15 each year, shrine decorations, talismans, and other shrine ornaments used during the local New Year Holidays are gathered together and burned in bonfires. They are typically pilled onto bamboo, tree branches, and straw, and set on fire to wish for good health and a rich harvest in the coming year. At these events, children throw their calligraphy into the bonfires -- and if it flies high into the sky, it means they will become good at calligraphy. For more on Tenjin belief, see the Encyclopedia of Shinto. For talismans, amulets, and folk practices, see Gabi Greve’s various pages: Tenmangu (Dazaifu) || Tenman Tenjin Sama 天神さま, a popular folk toy || Somin Shōrai Fu Amulets 蘇民将来符 || Uso 鷽 Bullfinch Tenjin Shrines 天神. Deceased individuals are sometimes deified and thereafter worshipped as Tenjin (lit. "heavenly spirit" or "heavenly god"). Shrines devoted to Michizane Sugawara 菅原道真 (845 - 903 AD) and to Emperor Meiji 明治天皇 (1852 - 1912 AD) are the two most prominent examples of Tenjin shrines. Michizane (courtier in the Heian period, noted poet and academic) was deified after death, for his demise was followed shortly by social unrest in the capital (Kyoto), said to be his revenge for being demoted and exiled to Dazaifu (Kyūshū). Michizane is the patron deity of scholarship, learning, and calligraphy. Every year on the 2nd of January, students go to his shrines to ask for help in the tough school entrance exams or to offer their first calligraphy of the year. Egara Tenjin 荏柄天神 (in Kamakura) is one of the three most revered Tenjin Shrines in Japan, and among the three largest. The other two are Dazaifu Tenmangū 大宰府天満宮 (near Fukuoka; Dazaifu is where Michizane was re-posted after his demotion; it is also where he died), and Kitano Tenjin 北野天神 in Kyoto (Michizane's birthplace). Of a total of about 90,000 Shinto shrines in Japan, there are about 11,000 Tenjin or Tenmangū shrines (editor: must find source of number). Around January 15 each year, shrine decorations, talismans, and other shrine ornaments used during the local New Year Holidays are gathered together and burned in bonfires. They are typically pilled onto bamboo, tree branches, and straw, and set on fire to wish for good health and a rich harvest in the coming year. At these events, children throw their calligraphy into the bonfires -- and if it flies high into the sky, it means they will become good at calligraphy. For more on Tenjin belief, see the Encyclopedia of Shinto. For talismans, amulets, and folk practices, see Gabi Greve’s various pages: Tenmangu (Dazaifu) || Tenman Tenjin Sama 天神さま, a popular folk toy || Somin Shōrai Fu Amulets 蘇民将来符 || Uso 鷽 Bullfinch

Ujigami Shrines 氏神. Clan-specific, or family-specific, shrines. The Ujigami 氏神 are clan or village deities who are responsible for a particular community or locality, and in many cases, they represent the ancestors who founded the village (e.g., Fujiwara Shrine, Kasuga Shrine, Tachibana Shrine, Umemiya Shrine). The protective deity of one’s birthplace is called Ubusunagami 産土神, and all the people living in one locality worshipping the local deity are called Ujiko 氏子.

Yakumo Shrines 八雲神社. See Yasaka Shrines.

Yasaka Shrines 八坂神社 (lit. = Eight Hills Shrine). Also known as Yakumo Shrines 八雲神社 (lit. = Eight Clouds Shrine). The central shrine is called Yasaka Shrine. It is based in Kyoto and was originally known as Gion-sha 祇園社. It was reportedly established in Kyoto 876 AD, but after the Meiji Restoration of 1868 and the government’s forced separation of Shintō and Buddhism, the shrine was renamed Yasaka Shrine. Its many sub-shrines around the country were also obliged to rename themselves, with many taking the name “Yakumo.” The main shrine in Kyoto serves as the headquarters of approximately 3,000 nationwide sub-shrines. Shrines in this group serve to protect people against epidemics and evil, as the main shrine in Kyoto (according to legend) was built to halt an epidemic brought upon the city by Gozu Tennō 牛頭天王 (the Ox-Headed god of epidemics), a syncretic Shintō-Buddhist deity of Indian origin. Gozu reversed his curse on Kyoto after the shrine was built to appease him. Shrines in this category also venerate deities of Shintō mythology -- especially Susano-o no Mikoto 須佐之男命, the impetuous, mischievous, and powerful Shintō deity who was cast down from heaven to earth for his indiscretions but later gained redemption. Over time, Gozu Tennō was assimilated with Susano-o, becoming the latter’s Buddhist counterpart. Both are powerful epidemic gods. Like Shinra Myōjin 新羅明神 (an epidemic god of Chinese origin said to expel pestilence and demons), both are fundamentally ambivalent deities -- they protect people from illness when worshipped properly but destroy people when ignored. Yasaka-Yakumo shrines also typically venerate Susano-o’s sister (sun goddess Amaterasu Ōmikami 天照大神), Susano-o’s wife (Kushinadahime / Inadahime 櫛名田比売 / 稲田姫), and the couple’s eight offspring deities (Yahashira no Mikogami 八柱 御子神). The couple also squired Ōkuninushi 大国主命, the popular Shintō kami of abundance, medicine, luck, and happy marriages. Ōkuninushi is venerated at the Grand Shrine of Izumo (Izumo Taisha 出雲大社) in Shimane Prefecture. In addition, Yasaka-Yakumo shrines venerate Amaterasu as the central representative of the Amatsukami 天つ神 (gods of heaven) and Susano-o as the central representative of the Kunitsukami 国つ神 (gods of earth).

Yasukuni Shrine 靖國神社. Established in 1869 as a memorial to Japan’s war dead. Soldiers, top military leaders, and war criminals from WWII are enshrined here. This has attracted much negative attention in recent decades from Japan’s Asian neighbors. China in particular expresses great dissatisfaction whenever the existing prime minister of Japan pays a visit to the site. Each year, in mid-July, the shrine also holds its Mitama Festival, a four-day festival to pray for the repose of 2.4+ million war dead, to display thousands of lanterns, and to conduct various rituals and entertainment events. See photos here (outside link)

LEARN MORE

Kokugakuin University

Shrine Links

Other Shintō Links

ū ā ō Ō

First published Jan. 2008

Last Update Dec. 6, 2011. Revised / added text, and posted new photos.

|

|