|

|

|

|

Rock Gardens, Dry Landscapes, Hill Gardens

Karesansui, Kasan, Tsukiyama, Others

This is a side page

Click here to return to “Stones Top Menu”

Click here for Flowers of Japan Photo Gallery

|

Lafcadio Hearn (1850-1904), a noted writer on Japan, said this about Japanese rock gardens: “In order to comprehend the beauty of a Japanese garden, it is necessary to understand -- or at least to learn to understand -- the beauty of stones. Not of stones quarried by the hand of man, but of stones shaped by nature only. Until you can feel, and keenly feel, that stones have character, that stones have tones and values, the whole artistic meaning of a Japanese garden cannot be revealed to you. Not only is every stone chosen with a view to its particular expressiveness of form, but every stone in the garden or about the premises has its separate and individual name, indicating its purpose or its decorative duty.”

Stone at Koyasan, photo by Gabi Greve

|

|

INTRODUCTION. The Japanese typically categorize their gardens into three broad types. A wonderful six-page review of Japanese gardens is offered by the Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO).

Tsukiyama 築山 is a term to denote a hill garden as opposed to a flat garden (hiraniwa 平庭). Tsukiyama gardens typically feature an artificial hill combined with a pond and a stream and various plants, shrubs, and trees. Such gardens can be viewed from various vantage points as you stroll along the garden paths, or appreciated from a particular temple building or house on the grounds. Representative examples can be found at Tenryuji Temple and Saihoji Temple, both in Kyoto. Tsukiyama literally means constructed mountain. The older term was kasan 仮山 (artificial mountain). Tsukiyama gardens became particularly popular in the early Edo period. One common type of Tsukiyama garden is the tortoise and crane garden, which typically shows these fortuitous creatures on two separate islands, together with an isle of eternal youth. Representative examples can be found at Daigoji Sanboin Temple and Kodaiji Temple, both in Kyoto. In Chinese and Japanese mythology, the turtle and crane are symbols of long life and happiness. For a few more details on tsukiyama gardens, click here. Tsukiyama 築山 is a term to denote a hill garden as opposed to a flat garden (hiraniwa 平庭). Tsukiyama gardens typically feature an artificial hill combined with a pond and a stream and various plants, shrubs, and trees. Such gardens can be viewed from various vantage points as you stroll along the garden paths, or appreciated from a particular temple building or house on the grounds. Representative examples can be found at Tenryuji Temple and Saihoji Temple, both in Kyoto. Tsukiyama literally means constructed mountain. The older term was kasan 仮山 (artificial mountain). Tsukiyama gardens became particularly popular in the early Edo period. One common type of Tsukiyama garden is the tortoise and crane garden, which typically shows these fortuitous creatures on two separate islands, together with an isle of eternal youth. Representative examples can be found at Daigoji Sanboin Temple and Kodaiji Temple, both in Kyoto. In Chinese and Japanese mythology, the turtle and crane are symbols of long life and happiness. For a few more details on tsukiyama gardens, click here.

-

Rock Garden

Hokokuji Temple

(Kamakura). Founded

in 1334 AD. Zen branch temple belonging to Kenchoji Temple

of the Rinzai Sect. |

Karesansui 枯山水 (dry landscape gardens, also known as rock gardens and waterless stream gardens) are typically associated with Zen Buddhism, and often found in the front or rear gardens at the residences (houjou 方丈) of Zen abbots. The main elements of karesansui are rocks and sand, with the sea symbolized not by water but by sand raked in patterns that suggest rippling water. Representative examples are the gardens of Ryoanji Temple and Daitokuji Temple, both in Kyoto. Plants are much less important (and sometimes nonexistent) in many karesansui gardens. Karesansui gardens are often, but not always, meant to be viewed from a single, seated perspective, and the rocks are often associated with and named after various Chinese mountains. The first-ever Zen landscape garden in Japan is credited to Kenchoji Temple in Kamakura. Founded in 1251, this temple was the chief monastery for the five great Zen monasteries that thrived during the Kamakura era (1185-1333). It became the center of Zen Buddhism thanks to strong state patronage. For more details on karesansui, click here.

Chaniwa 茶庭. With the introduction of the tea ceremony in the 14th century AD, the chaniwa (garden attached to the tea-ceremony house) also began to appear in Japan. In many cases, the chaniwa is not really a full-fledged garden, but rather a narrow path leading up to the chashitsu (the main tea room). The placement of the stepping stones that lead to the main tea room is a hallmark feature of this garden type. Chaniwa also feature stone lanterns and stone water basins (tsukubai), where guests purify themselves before partaking in the tea ceremony. The aim of the chaniwa designer is to create a feeling of solitude and detachment from the world, one that matches the aesthetic simplicity of the tea ceremony (Jp. = sadou or chadou 茶道). In Zen, minimalism and silent meditation are important ways to achieve enlightenment. Chaniwa gardens are not typically open to the public. Chaniwa 茶庭. With the introduction of the tea ceremony in the 14th century AD, the chaniwa (garden attached to the tea-ceremony house) also began to appear in Japan. In many cases, the chaniwa is not really a full-fledged garden, but rather a narrow path leading up to the chashitsu (the main tea room). The placement of the stepping stones that lead to the main tea room is a hallmark feature of this garden type. Chaniwa also feature stone lanterns and stone water basins (tsukubai), where guests purify themselves before partaking in the tea ceremony. The aim of the chaniwa designer is to create a feeling of solitude and detachment from the world, one that matches the aesthetic simplicity of the tea ceremony (Jp. = sadou or chadou 茶道). In Zen, minimalism and silent meditation are important ways to achieve enlightenment. Chaniwa gardens are not typically open to the public.

Zen, Tea, and Daruma Zen, Tea, and Daruma

The tea ceremony is closely associated with Zen Buddhism and the Indian sage Daruma (Bodhidharma). Daruma is the undisputed founder of Zen Buddhism, and credited with Zen's introduction to China during his travels to the Middle Kingdom sometime in the 5th or 6th century AD. Zen was introduced to Japan early in the Kamakura Era (1185-1333) and became a favorite of the new Warrior Class (samurai) who had wrested power from the nobility. The primary aim of Zen Buddhism is personal enlightenment, and according to Daruma, enlightenment cannot be found in books or sutras or in performing rituals. Rather, it is to be found within the self through meditation. Daruma taught that within each of us is the Buddha, and that meditation can help us remember our Buddha nature. By clearing our minds of distracting thoughts, by striving for a mental state free of material concerns, we will rediscover our lost but true Buddha nature.

The practice of Zen involves long sessions of zazen, or seated meditation, to clear the mind of distractions and to gain penetrating insight. Zen's assimilation into Japanese culture was accompanied by the introduction of green tea, which was used to ward off drowsiness during the lengthy zazen sessions. One Daruma legend says that Daruma brought green tea plants with him when he traveled to China; another says that Daruma plucked off his eyelids in a rage after dozing off during meditation -- the eyelids fell to the ground and sprouted as China's first green tea plants!! To this day an early form of the tea ceremony is carried out in some Zen monasteries in Japan in honor of Daruma. (Note: Zen Buddhism is the term used in Japan, but Daruma’s philosophy arrived first in China, where it flowered and was called Chan Buddhism. Only centuries later does it bloom in Japan, where it is called Zen). The practice of Zen involves long sessions of zazen, or seated meditation, to clear the mind of distractions and to gain penetrating insight. Zen's assimilation into Japanese culture was accompanied by the introduction of green tea, which was used to ward off drowsiness during the lengthy zazen sessions. One Daruma legend says that Daruma brought green tea plants with him when he traveled to China; another says that Daruma plucked off his eyelids in a rage after dozing off during meditation -- the eyelids fell to the ground and sprouted as China's first green tea plants!! To this day an early form of the tea ceremony is carried out in some Zen monasteries in Japan in honor of Daruma. (Note: Zen Buddhism is the term used in Japan, but Daruma’s philosophy arrived first in China, where it flowered and was called Chan Buddhism. Only centuries later does it bloom in Japan, where it is called Zen).

- Zen Garden Art. Hill gardens and dry landscape gardens are often designed to imitate the sweep of a vast landscape within a very limited space, and the subtle, minimal, and skillful arrangement of rocks, shrubs, trees, and running water are meant to provide the viewer with a heightened sense of natural scenic beauty. One of Japan’s most renowned early designers was Musou Kokushi 夢窓国師 (1275-1351). This famous Zen master, whose real name was Muou Soseki, is credited with the construction of 66 Zen temples throughout Japan, and with the design of dozens of Zen gardens, including those at Zuisenji Temple in Kamakura and at Tenryuji and Saihoji temples in Kyoto. He was also a noted writer of poems. Another celebrated gardener was Kobori Enshu 小堀遠州 (1579 - 1647). Kobori is credited with many dry landscape gardens in Japan, including that at Daitokuji Hojo (the Chief Abbot’s residence at Daitokuji Zen temple in Kyoto) and the garden at Kyoto’s Old Imperial Palace.

Without a speck of dust being raised,

the mountains tower up,

without a single drop falling,

the streams plunge into the valley.

An Ode to the Dry Landscape

by Muso Soseki (1275-1351)

- In general terms, the Japanese Zen gardener aims to cultivate as if not cultivating, as if the gardener were part of the garden. Indeed, Japanese Zen gardens often appear helped rather than governed by the gardener. With Zen, art aspires to represent not only nature itself but to become a work of nature. To paraphrase Alan Watts, Zen art is the “art of artlessness, the art of controlled accident.” For more on Zen art and its influence on Japanese artistic sensibilities, please click here.

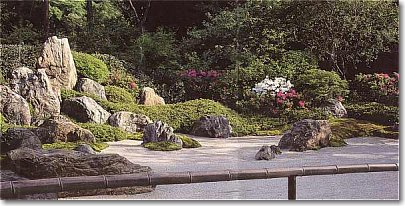

Karesansui Type

Rock Garden at Komyoji Temple (Jodo Sect) in Kamakura

Photo by Tadahiro Kondo

Above Photo. Says Tadahiro Kondo: “Karesansui gardens are usually found at Zen temples, and the most famous among them is that of Ryoanji in Kyoto. It is rare to find them in temples of the Jodo (Pure Land) sect. In May, beautifully trimmed satsuki, or Rhododendron indicum, in the garden will be in full bloom. I personally feel that the Komyoji garden here is more beautiful, or at least cleaner, than Ryoanji's, which is always crowded with sightseers. Worse still, at Ryoanji, an admission of 500 yen does not allow us to get access to the main hall. The Ryoanji garden attracts visitors with its enigmatic arrangement of 15 rocks (clustered so that one can see no more than 14 from any single angle).” For more details on Komyoji Temple, please see Mr. Kondo's web site.

Karesansui Type

Ryouanji 竜安寺 (Kyoto) Zen Garden

Constructed in 15th century; a world cultural heritage site

Photo courtesy of JAANUS

Karesansui Type

Toufukuji Houjou 東福寺方丈 (Kyoto)

Photo courtesy of JAANUS

|

Karesansui 枯山水 (かれさんすい)

Below text courtesy JAANUS

Literally "dry landscape." A common type of garden which suggests mountains and water using only stones, sand or gravel and, occasionally, plants. Water is symbolized both by the arrangements of rock forms to create a dry waterfall (karetaki 枯滝) and by patterns raked into sand to create a dry stream (karenagare 枯流). The word karesansui is found in the 11th century garden manual SAKUTEIKI 作庭記 and garden historians have designated Heian-period rock arrangemants as zenkishiki karesansui 前期枯山水. Karesansui usually refers to dry gardens of the Muromachi, Momoyama and Edo periods, although the term kouki karesansui 後期枯山水 has been created to distinguish this later type. Because of their similarity to ink monochrome landscape painting (suiboku sansuiga 水墨山水画), particularly that of the Chinese Northern Song (Hokusou 北宋) dynasty (960-1126), karesansui gardens are also called suiboku sansuigashiki teien 水墨山水画式庭園 or hokusou sansuigashiki teien 北宋山水画式庭園. Like paintings, the gardens are meant to be viewed from a single, seated perspective. In addition to the aesthetic similarities to Chinese painting, the rocks in karesansui are often associated with Chinese mountains such as Mt. Penglai (Jp; *Houraisan 蓬莱山) or Mt. Lu (Jp; Rosan 盧山). Given the multiple Chinese associations of karesansui gardens, they are the preferred type of garden for Zen 禅 temples (Buddhism having arrived from China in the 7 century) and the best examples are found in the front or rear gardens of Zen abbots' residences, houjou 方丈. Exemplary Muromachi period examples include the gardens at the Daisen'in 大仙院 in Daitokuji 大徳寺 and at Ryouanji 竜安寺. While Muromachi karesansui tend to use plants sparingly, early Edo period gardens of this type often contrast an area of raked gravel with a section of moss and larger plants along the rear wall. The gardens at the houjou and Konchi'in 金地院 at Nanzenji 南禅寺, and Shinju'an 真珠庵 and Oubai'in 黄梅院 at Daitokuji 大徳寺 are good examples. The aesthetic consonance with abstract art largely accounts for the resurgence of karesansui gardens both in Japan and abroad in the 20 century. A good example of a modern karesansui is Shigemori Mirei's 重森三鈴 1939 east garden at the Houjou 方丈 of Toufukuji 東福寺.

Kasan 仮山

Literally artificial mountain. Also kasansui 仮山水. A general term refering to an artificial mountain modeled on a real or legendary mountain. Usually built in a garden. Between one and five of these artificial hills would be built, and sometimes these could be climbed to enjoy a view of the garden. The idea of recreating mountains in a garden originated in China with models of ledgendary peaks such at Penglai (Houraisan 蓬莱山) and Kunlun (Konronsan 崑崙山), Daoist mountains of immortals, and Mt. Sumeru (Shumisen 須弥山) of the Buddhist cosmology. Small mountain models were also common in Japan since the Nara period. These could be made of ceramics, dried wood, or strangely-shaped stones, as seen in miniature tray landscapes, bonkei 盆景 and bonseki 盆石. Tsukiyama 築山, the modern term for hill garden, has generally replaced this more archaic term, kasan.

Tsukiyama 築山

Literally constructed mountain. The older term is kasan 仮山. Referring to an artificial hill in a garden, the term is used to denote a hill garden as opposed to a flat garden, hiraniwa 平庭. Tsukiyama gardens became particularly popular in the early Edo period. The importance of this term can be seen in the title of the garden manual TSUKIYAMA TEIZOUDEN 築山庭造伝 where it was virtually a synonym for the garden in general. <end quotes from JAANUS>

|

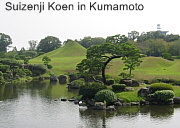

Tsukiyama Type, Suizenji Koen in Kumamoto

Built by the Hosokawa family in the 17th century. Miniature Mt. Fuji.

Photo by Jonathan Baker. His wonderful photo gallery is here.

See the album named “Kumamoto.”

Meigetsu-in Temple in Kita Kamakura

Meigetsu-in (Temple of the Clear Moon) in Kita Kamakura

Japanese landscape gardens are famous worldwide for their quiet beauty. Although meticulously cared for and highly artificial, Japanese gardens still appear extremely natural. This is one of the halllmarks of Zen Buddhist art (Chinese in origin). The first-ever Zen landscape garden in Japan is credited to Kenchoji Temple. Above photo scanned from Meigetsu-in entrance stub.

Perhaps the greatest watershed in Japanese aesthetics occurs with the introduction of Zen Buddhism during the Kamakura Era (1185-1333). The contribution of Zen to Japanese culture is profound, and much of what the West admires in Japanese art today can be traced to Zen influences on Japanese architecture, poetry, ceramics, painting, calligraphy, gardening, the tea ceremony, flower arrangement, and other crafts. For a review of Zen’s influence on Japanese art, please click here.

Modern, work by Japanese Potter Sugiura Yasuyoshi

from "Ash-Covered Ceramic Stones" Series

Photo by Hatayama Takashi

LEARN MORE

- Guide to Japanese Gardens -- Outside Resource

By the Japan National Tourist Organization. Excellent six-page review (Adobe PDF file) of gardens in Kyoto, Tokyo, and elsewhere.

- Japanese Gardening. Information on Japanese gardening including history, design and construction by Botanysaurus.

- Flowers of Japan -- Photo Gallery (this site)

- Japan National Tourist Organization - Garden Page

- Bowdoin College (Brunswick, Maine) Garden Pages

Dedicated to the gardens of Japan, and more specifically to the historic gardens of Kyoto and its environs. Includes many useful links and bibliographical references.

- Zen-Garden.org. An online guide for creating a karesansui garden. The site authors are based in the Netherlands, where they have created a Zen karesansui garden named TSUBO-EN. This site discusses how to create and maintain such a garden.

- International Association of Japanese Gardens

- Photo Gallery of Japanese Zen Gardens -- by Frantisek Staud

- Photo Gallery of Japan by Jonathan Baker (Many garden photos)

- Super Garden Parks in Japan

Three super gardens in Japan include the plum garden at Kenroku-en 偕楽園 in Mito, the Ritsurin Koen 栗林公園 in Takamatsu, and the Kouraku-en 後楽園 in Okayama. For a few more details on the plum garden at Kenroku-en, click here. For Kouraku-en and more, please see Dr. Gabi Greve’s web site.

- Japanese Architecture in Kyoto -- Garden Photos

web.kyoto-inet.or.jp/org/orion/eng/hstj/kita/daisenin.html

web.kyoto-inet.or.jp/org/orion/eng/hstj/histj.html

- Musou Kokushi

Mountain, Temple, and Design of Movement:

Thirteenth-Century Japanese Zen Buddhist Landscapes

Paper by Norris Brock Johnson

www.doaks.org/Motion/05Motion.pdf (30-page report)

- Dream Conversations by Muso Kokushi

ISBN 1-57062-206-X. A collection of written replies by Muso Soseki (aka Musou Kokushi) to questions about the true nature of Zen. To learn more or purchase the book, please click here. (Shambhala Publications)

- JGARDEN.ORG

Daitokuji Honjo -- Garden Photos

Biography of Musou Kokushi

- The Garden Art of Japan, by Masao Hayakawai, from the Heibonsha Survey of Japanese Art. Just one book in a wonderful 30-book series.

- Green Dragon Bonsai. Mail order suppliers of Japanese, Chinese and Korean Bonsai trees, pots, tools, and accessories. Free advice and articles for all levels. Green Dragon Bonsai is based in Prestatyn, North Wales.

This is a side page.

Click here to return to “Stones Top Menu”

|

|