|

OTHER IMPORTANT

PERIOD NAMES

Muromachi Period

室町時代 +1392-1573

Also known as Ashikaga Period

足利時代 +1392-1573

Nanbokuchō Period

Southern & Northern Courts

南北朝時代 +1336-1392

Warring States (Sengoku)

戦国時代 +1467-1568

Azuchi-Momoyama Period

安土桃山時代 +1568-1615

|

|

HISTORICAL SETTING HISTORICAL SETTING

The new and reformed Buddhist sects of the prior Kamakura period consolidated their gains, and Buddhism for the commoner thereafter remained a regular feature of Japan’s religious landscape. Pilgrimages to sacred sites devoted to Kannon Bosatsu, to the Ise Shinto shrines, and to the top of Mt. Fuji also became popular. Yoshimitsu 足利義満 (+1358-1408), the third Ashikaga Shōgun, ushered in a brief period of cultural renaissance, highlighted by the reopening of formal trade with China after a lapse of nearly 600 years, the building of great temples and palaces (e.g., the famous Kinkakuji 金閣寺 or Golden Pavilion in Kyoto), and strong patronage of the arts and Zen Buddhism. Nevertheless, the period was marked by incessant civil wars. Fighting lasted until the arrival of the “great unifer,” the feudal warlord Oda Nobunaga 織田信長 (+1534-1582), who marched into Kyoto in +1568 and captured the city. Oda needed a few more years to overthrown the Muromachi Bakufu 幕府, which he achieved with the abdication of the last Ashikaga Shōgun (Shogun) 足利将軍 in +1573.

Even so, many of Kyoto’s great art treasures were lost during the fighting, and the powerful Buddhist monestaries suffered greatly soon thereafter. The Tendai 天台 stronghold at Enryakuji Temple 延暦寺 on Mt. Hiei 比叡 was burnt to the ground in +1571 by Oda and its militant monks scattered. So too was the powerful Ishiyama Honganji Temple 石山本願寺 of the Jōdo Shinshu 浄土真宗 (True Pure Land) sect in Osaka, set to flame by Oda in +1580. The considerable political power of the entrenched Buddhist monasteries never recovered from this onslaught. They were no longer allowed large landholdings, lost various other economic advantages, and found their connections with the now-powerless imperial court of little value. Unlike the Tendai and Pure Land sects, the Zen denomination rose to prominence and political power during the Muromachi period, with many warriors turning to Zen Buddhism for release.

Another major feature of the age was Ikkō-ikki (一向一揆), literally "single-minded leagues." Ikki means “revolt.” The Ikkō-ikki were mobs of peasant farmers, monks, Shinto priests and local nobles, who rose up against samurai rule in the 15th and 16th centuries. They followed the beliefs of the Jōdo Shinshu (True Pure Land) sect of Buddhism which taught that anyone, noble or peasant, man or woman, could be saved by Amida Buddha's grace. They were organized to only a small degree.

In the end, Oda Nobunaga was betrayed by one of his generals (Akechi Mitsuhide 明智光秀 +1528-1582) and forced to commit ritual suicide in +1582. But the traitor was soon overthrown by Toyotomi Hideyoshi 豊臣秀吉 (+1536-1598), a loyal Oda ally, who then proceeded to eliminate rivals and succeeded in unifying Japan around +1590. In his efforts to gain control, Hideyoshi issued an edict in +1587 banning Christianity, although this edict was not enforced initally (e.g., Christian missionaries were still allowed to enter Japan in +1593). But in +1597, Hideyoshi had 26 Franciscans executed, and laws prohibiting the foreign religion continued unbated into the 1630s. After Hideyoshi’s death, another loyal Oda ally named Tokugawa Ieyasu 徳川家康 (+1542-1616) assumed control. In +1603, he founded the Tokugawa Shogunate 徳川将軍, which ruled Japan for the next 250 years from Edo 江戸 (modern-day Tokyo).

Buddhist Statuary in the Muromachi Period Buddhist Statuary in the Muromachi Period

Dark age of statue making. Why did statuary spiral downward?

Japan’s art historians say the Kamakura Period represented a great renaissance in Buddhist statuary. By the same token, the subsequent Muromachi Period is considered a “Dark Age.” Of the 2,609 works of sculpture designated as National Treasures 国宝 or Important Cultrual Properties 重要文化財 in Japan, not one piece from the Muromachi period is on the list of National Treausures, and only 90 Muromachi pieces are listed as Important Cultural Properties (and those only in recent decades). The reasons for this sudden decline of sculpture during the blood-soaked Muromachi centuries are hard to explain. First, Buddhism among the common folk was perhaps at its peak during the time, so the decline is extremely perplexing. Emily J. Sano, one-time curator of the Kimbell Art Museum in Texas, says this:

“The Kamakura Bakufu, or military government, supported the Zen sect, whose major aesthetic interests were literature and ink painting. It is possible, too, that realism itself (editor: the main achievement of the Kamakura era was realistic sculpture) contained the seeds of decline. Realism is capable of inspiring great art, but not necessarily great icons. The overall flavor of Kamakura-era sculpture is one of human sensuality, a feature that makes them intriguing as objects but unbelievable as gods. Icons are created for worship, but sculpture, because of its dimensional presence, draws the viewer into a physical participation with the object. If a divine image takes on the appearance of humans, it can no longer be worshipped, for the viewer is forced into a human relationship with the god. One wonders, therefore, if the splendid accomplishments of Kamakura art did not inevitably spell the downfall of sculpture as a religious expression in Japan.” <end quote from The Great Age of Japanese Buddhist Sculpture (AD 300 - 1300) > >

Other Potential Reasons for Decline

- Rise to prominence of Zen Buddhism, which focused on painting, calligraphy, the tea ceremony, and literature. Zen’s main devotional deity is Shaka Nyorai, the Historical Buddha, with little concern for the many other Mahayana deities.

- Declining power of the imperial family, and thus a drop in its patronage of Buddhist art and architecture.

- Incessant warfare among the nobility lessens Buddhist patronage among the great feudal clans.

- Techiques for the systematic mass-production of Buddhist statuary are perfected, formalized, and endlessly copied.

- Growing importance of secular art and folk crafts

|

|

|

|

Nikkō Bosatsu (holding red disc) & Gakkō Bosatsu. Important Cultural Properties of Zushi City, Japan.

Dated: Muromachi Period, 15th-16th Century, Wood. Jinmuji Temple 神武寺 (Tendai Sect) in Zushi City.

Yosegi Zukuri 寄木造 (Joined-Block Technique). Height: 58.0 cm and 59.5 cm.

|

|

Nikkō and Gakkō (see above photos) surround the main object of worship, a seated statue of Yakushi Nyorai located within the temple’s Yakushi Hall 薬師堂 (see image below). This Yakushi Triad 薬師三尊 (Yakushi Sanzon) is a Hidden Buddha 秘仏 (Hibutsu) and shown only once every 33 years. The next public showing will occur in 2017. However, the temple performs its annual housekeeping each year on December 13. In the morning, during this annual event, the triad is available for viewing and veneration. <Photos Courtesy Zushi City, Kanagawa Prefecture>

Yakushi Nyorai at Jinmuji Temple, Zushi City, Japan

Height = 69.8 cm, Joined Block Method, Muromachi Period

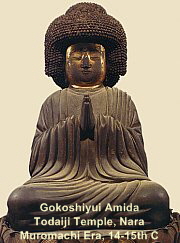

Gokō Shiyui Amida 五刧思惟阿弥陀 (aka Hōzō Bosatsu). Tōdaiji Temple (Nara), H = 106.6 cm, Muromachi Era.

Hōzō practiced for an inconceivably long time (five kapla = 五刧 = Gokō), and is thus shown here with thick hair.

Sculptors (Busshi) of the Muromachi Period

(followed by Workshop / Guilds of the Muromachi Period)

-

Chōyū (Choyu) 朝祐. Little is known about Chōyū's life (died 1426), but several extant pieces tell us he was active in the late 14th century and early 15th century in the Kamakura area. Among surviving works are a statue of Kokūzō Bosatsu, dated to 1390, at Nōmanji Temple 能満時 in Kawasaki City. It is a designated Important Cultural Property of Kawasaki City and Kanagawa Pref. See photo at right. Other extant pieces include standing wood images of the 12 Generals of Yakushi Buddha 十二神将 at Kakuonji Temple 覚園寺 in Kamakura (ranging in height from 150 cm to 190 cm), attributed to Chōyū and his team. Chōyū is also credited with wood carvings of Nikkō Bosatsu and Gakkō Bosatsu (dated 1422, H = 218-cm. each, also at Kakuonji) that flank the giant central image of Yakushi Buddha (H = 244 cm). See photo of this triad below. Kakuonji also possesses a statue of the deity Garanjin 伽藍神 (dated 1418) that is attributed to Chōyū. For more on Chōyū (Japanese only), see this J-site, which says Chōyū modeled his 12 Generals on another set installed at the now-defunct Tōkōji (Tokoji) Temple 東光寺 (originally located in the same neighborhood as Kakuonji). That set of 12 is also extant, and now on permanent display at the Kamakura Museum 鎌倉国宝館蔵, which is situated within Tsurgaoka Hachimangu Shrine in Kamakura city. <For more on 12 statues at Kakuonji, see this this J-Site> Chōyū (Choyu) 朝祐. Little is known about Chōyū's life (died 1426), but several extant pieces tell us he was active in the late 14th century and early 15th century in the Kamakura area. Among surviving works are a statue of Kokūzō Bosatsu, dated to 1390, at Nōmanji Temple 能満時 in Kawasaki City. It is a designated Important Cultural Property of Kawasaki City and Kanagawa Pref. See photo at right. Other extant pieces include standing wood images of the 12 Generals of Yakushi Buddha 十二神将 at Kakuonji Temple 覚園寺 in Kamakura (ranging in height from 150 cm to 190 cm), attributed to Chōyū and his team. Chōyū is also credited with wood carvings of Nikkō Bosatsu and Gakkō Bosatsu (dated 1422, H = 218-cm. each, also at Kakuonji) that flank the giant central image of Yakushi Buddha (H = 244 cm). See photo of this triad below. Kakuonji also possesses a statue of the deity Garanjin 伽藍神 (dated 1418) that is attributed to Chōyū. For more on Chōyū (Japanese only), see this J-site, which says Chōyū modeled his 12 Generals on another set installed at the now-defunct Tōkōji (Tokoji) Temple 東光寺 (originally located in the same neighborhood as Kakuonji). That set of 12 is also extant, and now on permanent display at the Kamakura Museum 鎌倉国宝館蔵, which is situated within Tsurgaoka Hachimangu Shrine in Kamakura city. <For more on 12 statues at Kakuonji, see this this J-Site>

Japanese scholars speculate that Chōyū was an important member of a group of sculptors active in the Kamakura area in the 14th and 15th century and loosely called the Chōha 朝派 or Kamakura Busshi 鎌倉仏師, for its members’ names all included the character Chō 朝. Although their lineage is unclear, they are generally given as Unchō 運朝, Chō-ei 朝栄, Seichō 清朝, Chōkei 朝慶, and Chōyū 朝祐. <Sources: J-Site 1 & J-Site 2>

Unchō 運朝 and Chōkei 朝慶 reportedly gained Hōgen 法眼 rank (the second highest rank awarded to Buddhist sculptors in those days). They are credited with a statue of Fudō Myō-ō (dated 1351) installed at Chōanji (Choanji) Temple 長安寺 (Kurihama, Kanagawa Pref.), just south of Kamakura. See photo below.

Unchō is also attributed with a wood statue of Shaka Buddha (Historical Buddha) at Kōgonji (Kogonji) Temple 光厳寺 (Tokyo) and a wood statue of Butsujō Zenji 仏乗禅師 at Hōkokuji (Hokokuji) Temple 報国時 (Kamakura), both dated to the mid-14th century. Butsujō Zenji is the posthumous title given to Hōkokuji's founding priest, Tengan Ekō 天岸慧広. <Source: this J-Site>

- Gengorō (Gengoro) 源五朗. Member of the Shukuin Sculpting Guild in Nara. Birth-death dates unknown.

- Genji 源次. Second-generation member of the Shukuin Sculpting Guild in Nara. 16th century.

- Genshirō (Genshiro) 源四郎. First-generation member of the Shukuin Sculpting Guild in Nara. 16th century.

- Genzaburō (Genzaburo) 源三郎. Third-generation member of the Shukuin Sculpting Guild in Nara. 16th century.

- Kankei 覚慶. Member of the 14th-century Tsubai Guild. Extant statues include Kisshōten (1340) at Kōfukuji Temple in Nara.

- Keishū (Keishu) 慶秀. Member of the 14th-century Tsubai Guild. Keishū 慶秀 reportedly helped restore the 11-Headed Kannon 十一面観音 at Kasuga Jingūji 春日神宮寺 (1368).

- Ken'en 憲円, also known as Sanjō Hōin Ken'en 三条法印憲円 (birth/death unknown; Kyoto Guild). Famous Kyoto-based sculptor of the 14th century. Extant wood statue of Jizō Bosatsu at Hōkaiji (Hokaiji) Temple 宝戒寺 in Kamakura, dated to 1365, and designated an Important Cultural Property. The statue is the first on the Kamakura Piligrimage to 24 Jizo Sites. See above photo of Kosodate Kyōyomi Jizō.

- Kōson (Koson) 弘尊. Takama Guild. Most celebrated sculptor of this workshop (15th century). He worked with Tsubai sculptor Shunkei 春慶 on the restoration of the 11-Headed Kannon 十一面観音立像 at Hasedera 長谷寺 in Nara.

- Kōshō (Kosho) 康正, b-d 1534-1621. A leading sculpture in the Keiha lineage, awarded Hōin 法印 status, the highest rank given to Buddhist sculptors. Also the head of the Shichijō Bussho 七条仏所 of Kyoto (Seventh Avenue Atelier), a major sculpting workshop of the Keiha school. Worked primarily at Tōji Temple 東寺 (Kyoto). Extant works include an effigy of Yakushi Nyorai and the 12 Generals in the Kondō 金堂 Hall at Tōji Temple. He is also attributed with creating the first Kyoto Daibutsu (Big Buddha of Kyoto), no longer extant. <Source: This J-site as well as Faith and Power in Japanese Buddhist Art (1600-2005) by Patricia J. Graham.>

- Shunkei 舜慶. One of the most prominent sculptors of the Tsubai Guild in Nara. Active in the late 14th to early 15th centuries. Student of Keishū 慶秀. Credited for a seated image of Kōbō Daishi 弘法大師 at Hōryūji Temple 法隆寺 in Nara, a statue of Kongō Rikishi at Kōfukuji Temple (dated sometime between 1394 and 1428), statues dated to 1380 of Kongara Dōji 矜羯羅 and Seitaka Dōji 制多迦童子 (attendants to Fudō Myō-ō) at Hōryūji Temple, and a seated image of Yakushi Nyorai at Hinzenji Temple 品善寺 in Nara (carved when he was 28 years old). He was awarded Hokkyō 法橋 rank during his lifetime, the third highest rank given to Buddhist sculptors. <Sources: this J-Site, Nara National Musem, JAANUS, others>

- Shunkei 春慶 (d. 1499). A prominent sculptor of the Tsubai Guild. Extant pieces include a 1459 statue of Gokei Monju Bosatsu 五髻文殊菩薩 (Monju with five topknots) at Hōryūji Temple 法隆寺 in Nara. Shunkei was awarded Hokkyō 法橋 rank in 1463, and in the next seven years carved statues of Shaka Nyorai (Historical Buddha) and Daikokuten 大黒天 for Kōfukuji Temple 興福寺 and statues of Bishamonten and Miroku for Gangōji Temple 元興寺 in Nara. In 1473, he carved the Amida Triad at Tōnomine Myōrakuji Temple 多武峰妙楽寺 in Nara, and in the next seven years carved other statues of Shaka, Yakushi, Jizō, Kannon, Monju, and others. In 1496, he was awarded Hōgen 法眼 rank (the second highest rank given to Buddhist sculptors). <Sources: this J-Site, Nara National Musem, JAANUS, others.>

- Takuma Jōkō (Takuma Joko) 宅間浄宏. A respected sculptor of the 14th century based in Kamakura. Extant pieces include a Jizō statue now installed at Raikōji Temple, Kamakura. See Jizō photos directly below. Takuma hailed from a family of sculptors and painters that lived and worked in the Kamakura area. It is sometimes referred to as the Takuma Bussho 宅間派 (Takuma Workshop, Takuma Guild). During his lifetime, Takuma Jōkō gained Hōgen (Hogen) 法眼 rank, the second highest rank awarded to Buddhist sculptors.

|

Jizō Bosatsu (wood)

Raikōji Temple (Kamakura)

14th Century, 131 cm

Carved by Takuma Jōkō 宅間浄宏

|

Jizō Bosatsu (wood)

Raikōji Temple (Kamakura)

14th Century, 131 cm

Carved by Takuma Jōkō 宅間浄宏

|

|

SAME STATUE AS PRIOR TWO PHOTOS

Ganjō Jizō 巖上地蔵. Lit. = Jizō Sitting Atop Rock.

Wood, Height 131 cm, Dated 1384. Carved by Takuma Jōkō 宅間浄宏

Important Cultural Property of Kanagawa Prefecture.

The pendant drapery is called the “hanging vestments style” (hōesuikashiki 法衣垂下式), which rose to great

prominence in Kamakura and the surrounding Kanto region in the late-Kamakura era and Nanbokuchō Period.

Photo: Magazine named 日本の仏像, 2007/10/25, No. 19 (Kondansha)

|

|

Shaka Nyorai (Historical Buddha) at Hōkokuji (Hokokuji) Temple 報国時 in Kamakura.

Wood, H = 50.6 cm. Central image of worship at this temple. Nanbokuchō Period 南北朝時代 +1336-1392.

This style of pendant drapery is called the “hanging vestment style” (hōesuikashiki 法衣垂下式), which rose

to great prominence in Kamakura and the Kanto region in the late-Kamakura era and Nanbokuchō Period.

Yakushi Triad (Yakushi Sanzon 薬師三尊) at Kakuonji Temple, Kamakura. ICA.

Nikkō Bosatsu on left (to your right) and Gakkō Bosatsu on right (to your left).

Nikkō (Sunlight) and Gakkō (Moonlight) statues attributed to sculptor Chōyū. Dated to 1422. H = 149.4 cm.

Inscription found in head of Nikkō statue says it was carved in 1422 by local sculptor Chōyū.

Central Yakushi image: H = 181.2 cm. Head dated to Kamakura Period and body to Muromachi Period.

The original central statue (attributed to Unkei) was destroyed in a fire in 1251 and remade in 1263.

The hanging vestments (hōesuikashiki 法衣垂下式), the large rahotsu 螺髪 (hair on head in spiral curls),

the facial features, and the slender fingers clearly reflect the influence of China’s Sung period (Sōdai 宋代).

These features also suggest that the Kamakura Busshi wanted to be independent from Kyoto culture or to rival it.

<Sources: Kondo Takahiro; Kakuonji Temple; Photo from magazine 日本の仏像, 2007/10/25, No. 19 (Kondansha).>

Central image of Fudō Myō-ō attributed to Unchō 運朝 and Chōkei 朝慶.

Fudō Myō-ō. Dated 1351. Hinoki (cypress), made from one piece of wood. H = 65.6 cm, crystal eyes.

Inscriptions within the statue attribute it to Unchō and Chōkei. <Photo from this J-Site>

Sculpting Guilds / Schools of the Muromachi Period

This section is indebted to the JAANUS database compiled by Dr. Mary Neighbour Parent (deceased). Like all prior periods in Japanese history, the Muromachi period gave rise to a number of sculpting guilds and workshops (Jp. = Bussho 仏所), also known as sculpting schools (Jp. = Ha 派).

- Nanto Busshi 南都仏師. Literally “Busshi of the South.” A general term for Buddhist sculptors working in Nara during and after the Kamakura period (13th to 14th centuries). Nara is considered the southern capital, Kyoto the nothern capital, but by this time political power was held by the military government much further north in Kamakura and the Kanto region. Several schools of Nanto Busshi were particularly important in the Muromachi period. The origins of the Nanto Busshi goes back to the time of Kakujo 覚助 (d. 1077), the son and successor of famed sculptor Jōchō (d. 1057). See Nanto Busshi Glossary for details. From their loins sprang the celebrated Nanto Busshi of the Keiha School 慶派 of sculptors, based originally at Kōfukuji Temple 興福寺 in Nara. Their most renowned artists were Unkei 運慶 (d. 1223) and Kaikei 快慶 (d. 1226). An innovative branch of the Keiha School known as the Zenpa School 善派 (closely associated with Saidaiji Temple 西大寺 in Nara) also emerged in the Kamakura period (13th century). This was followed by the emergence of the Nanto Busshi schools known as Tsubai Bussho 椿井仏所 in the 14th century, and then the Takama Bussho 高間仏所 and Shukuin Bussho 宿院仏師. The latter two were most active in the 15th and 16th centuries. Other schools set up in the mid-to-late 14th centuries include the Nobori-Ōji Bussho 登大路仏所 and Fujiyama Bussho 富士山仏所. Most of these schools / workshops survived into the Edo Period (1615-1868). For more details, see JAANUS Entry 1 and JAANUS Entry 2.

-

Shukuin Busshi 宿院仏師 and Shukuin Bussho 宿院仏所. Sculptors based in the Nara area. Came to prominence in the 16th century and prospered for some 80 years. Main workshop was called Shukuin Bussho 宿院仏所 (aka Shukuin Bussho-ya 宿院仏所屋), for they came from a location in Nara known as Shukuin 宿院. They were originally carpenters (Jp. = Tōryō 棟梁, Toryo) and wood craftsmen (Kiyose Banshō 木寄番匠). Shukuin was one of the first Bussho (workshops) where sculptors worked as laypeople without assuming the status of monks or without joining the monastic orders. See above list of Shukuin sculptors. Many of their artisans made wooden statues, often commissioned by small temples in the Nara area (e.g., Shaka 釈迦 and Yakushi 薬師 figures at Higashida Yakushidō 東田薬師堂). Other similar commercial workshops were active in the Edo Period (1615-1868), and the bussho system itself survived until the 19th century. The bussho model is credited to Jōchō (d. 1057). For more details, see this J-site. Shukuin Busshi 宿院仏師 and Shukuin Bussho 宿院仏所. Sculptors based in the Nara area. Came to prominence in the 16th century and prospered for some 80 years. Main workshop was called Shukuin Bussho 宿院仏所 (aka Shukuin Bussho-ya 宿院仏所屋), for they came from a location in Nara known as Shukuin 宿院. They were originally carpenters (Jp. = Tōryō 棟梁, Toryo) and wood craftsmen (Kiyose Banshō 木寄番匠). Shukuin was one of the first Bussho (workshops) where sculptors worked as laypeople without assuming the status of monks or without joining the monastic orders. See above list of Shukuin sculptors. Many of their artisans made wooden statues, often commissioned by small temples in the Nara area (e.g., Shaka 釈迦 and Yakushi 薬師 figures at Higashida Yakushidō 東田薬師堂). Other similar commercial workshops were active in the Edo Period (1615-1868), and the bussho system itself survived until the 19th century. The bussho model is credited to Jōchō (d. 1057). For more details, see this J-site.

- Takama Bussho 高間仏所 or Takaya Bussho 高矢仏所. A school of Buddhist sculptors active in Nara in the Muromachi period (15th-16th centurries). A branch of the Tsubai Bussho 椿井仏所. Its most celebrated sculptor is Kōson (Koson) 弘尊 of the 15th century. <Source: JAANUS>

- Tsubai Bussho 椿井仏所. Also written 津波井仏所. Guild of Buddhist sculptors active in Nara from the mid-14th to 16th century, named after their location at Kōfukuji Tsubaigō 興福寺椿井郷 in Nara. Other major workshops, like the Takama Bussho 高間仏所, Nobori-Ōji Bussho 登大路仏所, and Fujiyama Bussho 富士山仏所, were probably offshoots of the Tsubai Bussho, but all declined during the 16th century, when the Shukuin Bussho 宿院仏所 became dominant. The Tsubai Bushho was reportedly founded by Keiha 慶派 sculptors who formed an independent workshop. The most celebrated sculptors of the Tsubai Bussho are Kankei 覚慶, Keishū 慶秀, Shunkei 舜慶, and Shunkei 春慶. The Kishi Monju Bosatsu 文殊菩薩 statue (1378) at Jōdoji Temple 浄土寺 in Hiroshima prefecture bears the inscription Nanto Tsubai-saku 南都津波居作, giving testiment to the activities of this workshop. In the 15th century, the Takama Bussho 高間仏所, Nobori-Ōji Bussho 登大路仏所, and Fujiyama Bussho 富士山仏所 apparently emerged as offshoots of Tsubai Bussho. The best known sculptors of the Tsubai Bussho include Kankei, Keishū, Shunkei (1), and Shunkei (2). Others include Jōkeiin 成慶, Seikei 清慶, Shūkei 集慶, 椿井丹波公, 椿井次郎, and 椿井式部ら.<Source: JAANUS>

Nyoirin Kannon 如意輪観音像, Raikōji (Raikoji) Temple 来迎寺 (Kamakura City).

Wood with domon crests (see photo below). Dated to Nanbokuchō Period 南北朝時代.

The Nyoirin Kannon 如意輪観音 statue at Raikōji Temple in Kamakura features a beautiful domon 土紋, or clay crest. The domon technique was used for decorating Buddhist statues and is unique to Kamakura, and is thus also known as Kamakura Domon 鎌倉土紋. Clay is kneaded 練 (neru) into patterns or placed in molds and then affixed to the statue with lacquer, resembling a relief. The crests on this statue are said to ward off evil (厄除け yakuyoke) and to ensure easy delivery (安産 anzan) to women in labor. Statue dated to 14th century.

Legend About This Statue: A sad story about the Nyoirin Kannon tells about a man in Yui (由比), who was living a luxurious life, with not a care in the world. The man had a daughter he loved very much, but one day a large eagle swooped down and carried her off. The father frantically searched for his daughter, and although he eventually found her, she was dead. He interred her remains inside the body of this Nyoirin Kannon for the repose of her soul. <legend quoted from the Kamakura Citizens Net, as told by the temple>

Major Periods of the Muromachi Era

- Famous Artists in Muromachi Period. Tokyo National Museum, http://www.tnm.go.jp/en/

Zen and Ink Paintings: Kamakura and Muromachi Periods (12c-16c). This gallery features works by famous artists of the landscape-painting genre, along with famous works of bokuseki (calligraphy by Zen priests). Current exhibit includes: Geju (Verse in Praise of the Buddha), By Muso Soseki, Nanbokucho period, 14th century Landscape of the Four Seasons, Attributed to Shubun, Muromachi period, 15th century (Important Cultural Property)

- Muromachi Jidai 室町時代. JAANUS http://www.aisf.or.jp/~jaanus/deta/m/muromachijidai.htm

Also Ashikaga jidai 足利時代. The Muromachi period, 1392-1568. The period derives its name from a district in Kyoto which served as the location for the unification of the Southern and Northern Courts in 1392 under the Ashikaga 足利 shogunate (see *Nanbokuchou jidai 南北朝時代) until the entrance of Oda Nobunaga 織田信長 (1534-82) into the capital in 1568. Occasionally sources give 1333 as a beginning date, thus including the Nanbokuch・era within the period. The Ashikaga palace at Muromachi was actually completed in 1378, but no sources begin the period with this date. Many scholars put the final year at 1572 (or 1573) when the last Ashikaga shougun 足利将軍, Ashikaga Yoshiaki 足利義昭, was deposed by Nobunaga. Alternately, some political historians treat the Muromachi period as lasting only until the start of the Ounin Wars, Ounin-no-ran 応仁の乱 in 1467, after which it becomes the *Sengoku jidai 戦国時代 (Warring States period). The period is especially notable for ink painting *suibokuga 水墨画.

- Nanbokuchou Jidai 南北朝時代, Southern and Northern Dynasties Period

JAANUS http://www.aisf.or.jp/~jaanus/deta/n/nanbokuchoujidai.htm. The Southern and Northern Court period (1336-92). It takes its name from two separate antagonistic Imperial courts supported by their respective military clans which fought to establish their right to sole legitimate rule. While the Northern Court was still in Kyoto, the Southern Court was established at *Yoshino 吉野, south of Kyoto (modern Nara, therefore the period is also called *Yoshino jidai 吉野時代). Perhaps in response to the almost continual wars throughout the country, particularly in the capital, many warriors turned to Zen 禅 Buddhism which was introduced from China at this time, resulting in significant advances in Zen-related arts (see *suibokuga 水墨画). Some sources place the beginning of the period at 1333, when the Houjou 北条 regents were destroyed, rather than at 1336, when Emperor Godaigo 後醍醐 (1288-1339) first established his court at Yoshino. The two imperial lines were rejoined in 1392.

- Sengoku Jidai 戦国時代, Warring States Period

JAANUS http://www.aisf.or.jp/~jaanus/deta/s/sengokujidai.htm. Lit. The period began with the outbreak of the Onin Wars (Ounin no ran 応仁の乱, 1467-1477) and lasted up to the entrance of the great unifier Oda Nobunaga 織田信長 (1534-1582) into Kyoto in 1568. The term is used to refer to the Late Muromachi period (*Muromachi jidai 室町時代 kouki 後期), when many areas of the country were locked in civil war. One source also suggests 1491 as a beginning for the period, that being the year in which Houjou Souun 北条早雲 (1432-1519) destroyed the Horikoshi 堀越. Others include with it the subsequent Momoyama period (*Momoyama jidai 桃山時代; 1568-1615). The period of 100 years (1467-1568) devastated the city of Kyoto destroying countless numbers of art treasures during the fighting. The term "Warring States" was adopted from the Chinese Zhanguo 戦国 period (ca 403-221 BC). the most memorable artistic trend of the period is the early Kano style developed by Kanou Masanobu 狩野正信 (1434-1530) and Kanou Motonobu 狩野元信 (1476-1559). Motonobu's greatest surviving work is at Reiun'in 霊雲院 built in 1543 in Myoushinji 妙心寺. Kanou artists decorated large screens (*byoubu 屏風) and sliding door panels (*shouhekiga 障壁画) in Shogunal residences and temples, many of which were destroyed in the century long skirmishes mentioned above.

ENGLISH RESOURCES

- JAANUS. Japanese Architecture & Art Net Users System. Online database devoted to Japanese art history. Compiled by the late Dr. Mary Neighbour Parent, it covers both Buddhist and Shintō deities in great detail and contains over 8,000 entries.

- Dr. Gabi Greve. See her page on Japanese Busshi. Gabi-san did most of the research and writing for the Edo Period through the Modern era. She is a regular site contributor, and maintains numerous informative web sites on topics from Haiku to Daruma. Also see this Gabi page on Muromachi era. Many thanks Gabi-san !!!!

- Heibonsha, Sculpture of the Kamakura Period. By Hisashi Mori, from the Heibonsha Survey of Japanese Art. Published jointly by Heibonsha (Tokyo) & John Weatherhill Inc. A book close to my heart, this publication devotes much time to the artists who created the sculptural treasures of the Kamakura era, including Unkei, Tankei, Kokei, Kaikei, and many more. Highly recommended. 1st Edition 1974. ISBN 0-8348-1017-4. Buy at Amazon

. .

JAPANESE RESOURCES JAPANESE RESOURCES

- National Treasures and Important Cultural Properties

Japanese only. Searchable database provided by The Agency for Cultural Affairs. Search by era, artist, prefecture, etc.

- Kanagawa Prefecture, Search for Designated Sculptural Treasures

Japanese only. Numerous pieces from the Muromachi era.

- Kawasaki City (Kanagawa Pref.) List of City / Prefectural Treasure

Japanese only. Numerous pieces from the Muromachi era.

- Numerous Japanese-language temple and museum catalogs, magazines, books, and web sites. See Japanese Bibliography for extended list.

- Bunkaken.net. Busshi & Deity Reviews. Also see lineage chart.

- Site by M. Katada with Keiha lineage chart.

- Japan’s National Treasures and Busshi Data.

- Inpa, Enpa, and Keiha Lineage Charts.

- Kyoto Busshi by Period from Encyclopedia of Kyoto.

- Hidden Buddha, Walking Around Kyoto Monthly Magazine.

- Another Lineage Chart (npo.butuzou.net).

- Important Busshi and Lineage Chart.

- Japanese Postal Stamps of Buddhist Deities (for fun)

|