|

|

|

|

THIS IS A SIDE PAGE

THIS IS A SIDE PAGE

RETURN TO MAIN JIZO PAGE

Sai no Kawara 賽の河原

Riverbed of the Netherworld

Japanese Limbo for Children

WHAT’S HERE

- Dōsojin (Dosojin). Pre-Buddhist Japanese folk deities who administer the border between this world and hell; later incorporated into Japanese Buddhist mythology. The Dōsojin protect mountain passes, crossroads, and village boundaries, obstructing the passage of evil entities and demons of disease. Jizō is the Buddhist counterpart (honjibutsu 本地仏) of the Dōsojin.

Details here. Details here.

Sai no Kawara Mythology -- Children’s Limbo in Japan. Explores Japanese Buddhist mythology regarding the sandy beach called Sai no Kawara (Sainokawara), a riverbed in the netherworld where the souls of departed children do penance; reviews the savior role played by Jizō Bosatsu. Answers various questions, e.g., Why are stones piled around Jizō statues? Why are Jizō statues often found together in groupings of six? Why are Jizō statues garbed in red caps and bibs? Sai no Kawara Mythology -- Children’s Limbo in Japan. Explores Japanese Buddhist mythology regarding the sandy beach called Sai no Kawara (Sainokawara), a riverbed in the netherworld where the souls of departed children do penance; reviews the savior role played by Jizō Bosatsu. Answers various questions, e.g., Why are stones piled around Jizō statues? Why are Jizō statues often found together in groupings of six? Why are Jizō statues garbed in red caps and bibs?  Details here. Details here.

- Sai no Kawara (Sainokawara) -- Hymn to Jizo. The Legend of the Humming of the Sai-no-Kawara. A translation by Lafcadio Hearn of the Jizō hymn sung at Sai-no-Kawara rites. This hymn is about 300 years old.

Details here. Details here.

- Judges of Hell, Ten Kings of Hell, Demons of Hell. Describes the ten judges of hell, who review the behavior of the deceased while s/he was still living, and then send the departed soul back into one of six states of transmigration (reincarnation); introduces the demons who inhabit the lower regions, including the old hag Datsueba (literally “old woman who robs clothes”).

Details here. Details here.

- List of Sai no Kawara Locations in Japan. A partial list of Japanese locations where Sai-no-Kawara rites are still performed, along with brief details on female shamans (called Itako) who help grieving parents contact their departed children in the neitherworld.

Details here. Details here.

- Weddings for the Dead (Sai no Kawara).

Details here. Details here.

- Kokeshi and Infanticide in Japan.

Details here. Details here.

DŌSOJIN (or DOSOJIN) 道祖神 DŌSOJIN (or DOSOJIN) 道祖神

Shinto Deities Who Administer

Border Between This World & Hell

Adapted from text by JAANUS

SHINTO MYTHOLOGY. Also called Dōrokujin 道陸神, Sae no Kami 塞の神 (also read Sai no Kami), and other less common names. Japanese folk deities (or diety), later incorporated into Buddhism, who administer the border between this world and hell; also associated closely with roads and travel. In their most common Japanese manifestations, Dōsojin protect mountain passes, crossroads, and village boundaries, obstructing the passage of evil entities and demons of disease. The Dōsojin cult is intermingled with many others, both Shintō and Buddhist, including those practicing Sai-no-Kawara 塞の河原 rites (see below) for the souls of departed children, as well as rituals to ward off evil spirits. Dōsojin are also associated with matters of fertility both in crops and humans beings. Dōsojin is a term used to refer to the many protective stone markers found throughout Japan, especially those that are phallic or carved to show a single figure or a couple who may be in sexual union. In some cases, Dōsojin are considered the gods of stone. Click here for more on Dōsojin stone markers.

Dōsojin's Honjibutsu 本地仏 (Buddhist counterpart) is Jizō Bosatsu. Dōsojin's festival (called Dondo Matsuri ドンド祭, Sai no Kami 塞の神, or Sagichō 左義長) is celebrated on the 15th and 16th of the first lunar month (koshōgatsu 小正月) and is a children's festival. <end JAANUS text> Dōsojin's Honjibutsu 本地仏 (Buddhist counterpart) is Jizō Bosatsu. Dōsojin's festival (called Dondo Matsuri ドンド祭, Sai no Kami 塞の神, or Sagichō 左義長) is celebrated on the 15th and 16th of the first lunar month (koshōgatsu 小正月) and is a children's festival. <end JAANUS text>

The Japanese countryside is also home to many stone markers called kekkai-ishi (boundary stones 結界石). These stones once demarcated restricted zones inside the holy mountain sites of Japan's Shugendō (Shugendo) Sect (mountain ascetics). Shugendō combined elements of ancient pre-Buddhist worship with the doctrines and rituals of Esoteric Buddhism. Mountain worship in Japan is referred to as Sangaku Shinkō 山岳信仰, which literally means "mountain faith." Records suggest such worship emerged well before the introduction of Buddhism to Japan. At first, these restricted zones could not be crossed by any unclean person, but in later centuries these off-limit areas became exclusively closed to only women (Nyonin Kekkai 如人結界). For example, women were not allowed to scale Mt. Fuji until the time of the Meiji Restoration (1868). Today, however, these boundary zones have mostly disappeared. Also probably related to the kekkai-ishi are the uba-ishi (old woman stones or witch stones 姥石), shibari-ishi (binding stones 縛り石), and Shibarare Jizō (string-bound Jizōo, 縛られ地蔵). Please click here for a wonderful paper by Gorai Shigeru on Shugendō lore and boundary stones, written for the Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. For more on Dōsojin, click here.

SAI NO KAWARA MYTHOLOGY -- LIMBO FOR CHILDREN

The Role of Jizo Bosatsu in Saving Lost Souls

BUDDHIST MYTHOLOGY. In Japan, Jizō Bosatsu first appears in the Ten Cakras Sutra 大方広十輪経 in the Nara Era (710 to 794 AD). That sutra is now a treasure held by the Nara National Museum. In China, Jizō worship can be traced back to at least the fifth century AD (to the Chinese translation of the Ten Cakras Sutra), which portrays Jizō as the guardian of souls in hell. Chinese artwork thereafter often shows Jizō surrounded by the ten kings/judges of hell to signify Jizō’s primary role in delivering people from the torments of hell.

In Japan, the height of Jizō’s early popularity was during the late Heian Era (794 to 1192 AD) when the rise of the Jōdo (Jodo) 浄土宗 (Pure Land Sect devoted to Amida Nyorai) intensified fears about hell in the afterlife and kindled belief in redemption and salvation through Amida Nyorai. The Jōdo sect promised all -- monks and laity alike -- the chance for rebirth in Amida’s heavenly Western Paradise (Gokuraku 極楽, literally the “Land of Ultimate Bliss,” also called Jōdo 浄土, or Pure Land).

At the time, fears of hell were fired by a widespread belief in the Age of Mappō (Mappo) 末法 (Decline of Buddhist Law). During this period, the "Days of the Dharma" were divided into three periods in Japan (although other schemes were used by the Chinese, with the 500/1000 year pattern most prevalent):

- First phase (Jp. = Shōbō or Shobo 正法) lasting 1,000 years, during which Buddhism gains acceptance and spreads, and followers have the capacity to understand and practice Buddhist law. This is the period following the death of the Historical Buddha. According to the calendar of those days, the Historical Buddha died in 949 BC.

- Second phase lasting 1,000 years, in which Buddhist practice begins to weaken. Called the Period of the Imitation Law (Jp. = Zōhō or Zoho 像法), this phase would last until 1051 AD.

- Last phase lasting 3,000 years, the Age of Mappō, or the Period of the Decline of the Law, a time when Buddhist faith deteriorates and is completely abandoned.

The Japanese believed the third and final period -- the Age of Mappō (Decline of the Law) -- had begun in 1052 AD. The ensuing decades, moreover, were marked by civil wars, famine, and pestilence. A sense of foreboding thus filled the land, and people from all classes yearned for a gospel of salvation.

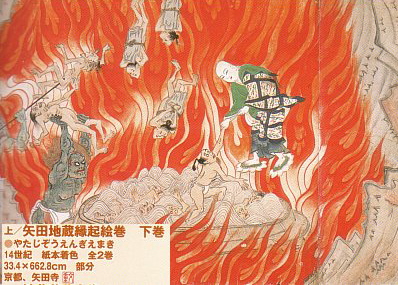

These fears gave rise to numerous tales and paintings depicting the torments and demons of hell. Perhaps one of the most popular books of the period, one that sparked vivid paintings of hell and hell beings, was “Essentials of Salvation” (Jp. = Ōjō Yōshū or Ojo Yoshu 徃生要集), written by the Tendai monk Genshin 源信 (942 - 1017 AD). The book itself focuses on the three main sutras of the Pure Land tradition, and is famous for its descriptions of hell and samsara (the cycle of suffering and rebirth). Even today, there are those who believe the current stage of human history is within the third phase, the Age of Mappō, the age when Buddhist faith deteriorates, is abandoned, and finally disappears. These fears gave rise to numerous tales and paintings depicting the torments and demons of hell. Perhaps one of the most popular books of the period, one that sparked vivid paintings of hell and hell beings, was “Essentials of Salvation” (Jp. = Ōjō Yōshū or Ojo Yoshu 徃生要集), written by the Tendai monk Genshin 源信 (942 - 1017 AD). The book itself focuses on the three main sutras of the Pure Land tradition, and is famous for its descriptions of hell and samsara (the cycle of suffering and rebirth). Even today, there are those who believe the current stage of human history is within the third phase, the Age of Mappō, the age when Buddhist faith deteriorates, is abandoned, and finally disappears.

Due to Jizō’s association with the realm of death and suffering souls (hell), Jizō worship became intimately associated with Amida worship, the Pure Land sect, and belief in Amida’s Western Paradise (and life in the beyond, in the afterlife). But faith in Amida and Jizō remain largely confined to a small segment of the Japanese population until the Kamakura Era (1185-1333 AD), when both are popularized by new Buddhist sects devoted to ordinary people -- the Pure Land Sects of Honen Shonin (1133 - 1212 AD) and his disciple Shinran (1173 - 1262 AD). Both sects were committed to bringing Buddhism to the illiterate commoner; both expressed concern for the salvation of ordinary people, stressing pure and simple faith over complicated rites and doctrines. Their leaders taught that anyone could attain salvation by faithfully reciting the name of Amida Buddha. The Nichiren Sect, however, which also came to prominence among common folk during the Kamakura Era, rejects the “quick path” to salvation represented by Amida faith. The Nichiren Sect therefore does not revere Amida or Jizō. <Editor’s Note: For reasons unknown to me, and surprisingly, the Jōdo Shinshu (New Jōdo Sect devoted to Amida) does not revere Jizō Bosatsu. This must be researched more fully.>

SAI NO KAWARA LEGEND SAI NO KAWARA LEGEND

WHY ALL THE STONES?

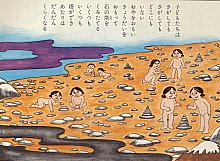

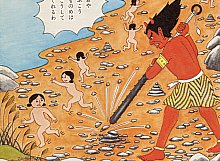

The legend of Sai no Kawara is attributed to the Jōdo Pure Land Sect from around the 14th or 15th century AD. According to the legend, children who die prematurely are sent to the underworld as punishment for causing great sorrow to their parents. They are sent to Sai no Kawara, the riverbed of souls in purgatory, where they pray for salvation by building small stone towers, piling pebble upon pebble, in the hopes of climbing out of limbo into paradise. But hell demons, answering to the command of the old hag Shozuka no Baba (also called Datsueba, or Jigoku no Baba), soon arrive and scatter their stones and beat them with iron clubs. But no need to worry, for Jizō comes to the rescue.

According to the Flammarion Iconographic Guide to Buddhism: "In Japan, popular belief holds that a hideous creature by the name of Shozuka-no-Baba strips children of their clothing, then encourages them to make piles of stones to build a stairway to paradise. Jizō consoles the afflicted children and, to save them, hides them in the wide sleeves of his robe. The Japanese in the countryside often attach small pieces of children's clothing to Jizō statues, believing that Jizō can thus clothe the children in his protection." <end Flammarion quote>

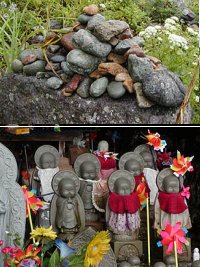

Even today, Jizō statues in some places in Japan are covered -- sometimes from top to bottom -- in pebbles placed there by sorrowing parents, who believe that every stone tower they build on earth will help the soul of their dead child in performing his/her penance. Also, you will often find statues of Jizō Bosatsu decked in red caps or bibs. For more on this “red” tradition, please see The Color Red in Japanese Mythology.

Below drawings from comic book named おじぞうさま (Daido Publications 大道社, Tokyo)

Order the comic book -- #3 -- online at www.seihon.co.jp/CCP002.html (J-site only)

(L) Children Piling Stones of Prayer; (R) Demon Attacker.

Saying prayers for father, they heap the first tower.

Saying prayers for mother, they heap the second tower.

Saying prayers for their brothers, their sisters, and all

whom they loved at home, they heap the third tower.

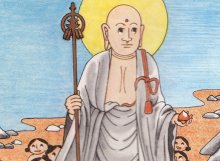

Jizō Bosatsu Comes to the Rescue

Jizō says:

“In this land of the shades,

I am your father and your mother.

Trust me morning and evening.”

JIZŌ AND THE SIX REALMS

CHILDREN IN LIMBO MUST UNDERGO JUDGEMENT

Below text adapted from writings of Kondo Takahiro.

Jizō Bosatsu vowed to save or relieve the suffering of all souls in each of the Six Realms of Existence (reincarnation), in particular those in hell, and is thus often shown in groupings of six in Japan. Such groupings are called Roku Jizō 六地蔵 -- literally the “Six Jizō.” Each of the six Jizō is assigned to one of the six realms (aka the Six Paths of Transmigration or Reincarnation, the Wheel of Life, the Cycle of Suffering), to save souls wandering in each specific realm. The six realms start with the lowest three states, called the three evil paths. They are the states of (1) people in hell, (2) hungry ghosts, and (3) animals. Above these are the states of (4) Asuras, (5) Humans, and (6) Devas. All six realms are stages of suffering, even the heavenly realm of the Deva, who it is said suffer from pride. There is a corresponding group known as the Six Kannon, one each for the six realms, which may have pre-dated the Six Jizō.

Jizō Bosatsu guards not only adult souls -- Jizō also guards the souls of children, particularly those of stillborn and aborted children, or of children who died early in life. These children, even if innocent, must still pass through the netherworld and undergo judgment by the Jūō (Juo) 十王 = Ten Kings of Hell.

Roku Jizō (Six Jizō) at Hase Dera in Kamakura

The first judge is Shinko-o. The dead who are found innocent can walk atop a bridge to cross the River Sanzu (River of Three Crossings | 三途の川 | さんずのかわ | the River Styx in Western myth), which lies between the first and second Judges of Hell (between the kings Shinko-o and Shoko-o). In most accounts, Jizo Bosatsu guides the innocent children across the bridge. The guilty, however, must swim across deep water and the less guilty must ford a rapid stream. In other accounts, Jizo helps the children wade the river safely. The story goes like this. When the souls of the deceased young children attempt to swim across the River Sanzu, they are overcome, for the river is too long or flowing too fast to cross. So instead, they build stone towers, pebble by pebble, as penance and prayer to receive salvation. But to no avail. For demons appear out of nowhere and destroy their stone towers -- thereby destroying any hope of crossing the river. However, if living parents and relatives have faith in Jizo Bosatsu, Jizo will come to their aid, and help their lost children wade the river safely, avoiding the terrible fury of the demons. Jizo statues, moreover, typically hold the shakujo -- a six-ringed staff -- a staff that is used by Jizo to fathom the river, and a staff that signifies Jizo’s protection for all trapped in the six realms. In some traditions, Jizo shakes the staff to awaken us from our delusions.

Jizo as depicted in the Tateyama Mandala

Even today, this folklore about hell prompts many Japanese parents into action. They imagine their little babies lingering at the riverbed, unable to cross the river, unable to gain salvation. Japanese parents therefore feel a great need to do something to alleviate their child’s suffering, to do something to improve the child’s chance of redemption. Thus the great cult of Jizo Bosatsu in Japan. Everywhere, throughout the country, at roadsides, in graveyards, in temples, at busy intersections, one can find little Jizo statues clothed in small bibs, adorned with toys, wearing tiny hats, protected by scarfs, and piled high with tiny stones offered by sorrowing parents. Parents cloth the Jizo statues in hopes that Jizo will clothe the dead child in his protection. Small pebbles are piled around the Jizo statue as well, offered by sorrowing parents as a prayer to Jizo to help the suffering soul of their deceased child.

Some temples, without doubt, take advantage of this folklore. They say to the traumatized parents: “Your lost child will continue to suffer. Your lost child will never be saved unless you take action to soothe their troubled souls. You must buy statuettes and offer religious services to alliviate their suffering.” In Japan, this Buddhist tendency toward mercy and prolonged mourning means that many grieving parents buy expensive statuettes and pay exorbitant fees for memorial services -- the temples thus prosper from such patronage. <end text adapted from writings of Kondo Takahiro>

Jizo Wasan (和 讃 = Wasan = Hymn or Psalm)

The Legend of the Humming of the Sai-no-Kawara

from “Glimpses of an Unfamiliar Japan” by Lafcadio Hearn

First published in 1894. ISBN: 0781230713

“Now there is a wasan of Jizo,” says Akira, taking from a shelf in the temple alcove some much-worn, blue-covered Japanese book. ”A wasan is what you would call a hymn or psalm. This book is two hundred years old. It is called Sai-no-Kawara-kuchi-zu-sami-no-den, which is, literally, The Legend of the Humming of the Sai-no-Kawara. And this is the wasan.” And he reads me the hymn of Jizo -- the legend of the murmur of the little ghosts, the legend of the humming of the Sai-no-Kawara, rhythmically, like a song:

Not of this world is the story of sorrow.

The story of the Sai-no-Kawara,

At the roots of the Mountain of Shide;

Not of this world is the tale; yet 'tis most pitiful to hear.

For together in the Sai-no-Kawara are assembled

Children of tender age in multitude,

Infants but two or three years old,

Infants of four or five, infants of less than ten:

In the Sai-no-Kawara are they gathered together.

And the voice of their longing for their parents,

The voice of their crying for their mothers and their fathers

-- “Chichi koishi! Haha koishi!" --

Is never as the voice of the crying of children in this world,

But a crying so pitiful to hear

That the sound of it would pierce through flesh and bone.

And sorrowful indeed the task which they perform.

Gathering the stones of the bed of the river,

Therewith to heap the tower of prayers.

Saying prayers for the happiness of father, they heap the first tower;

Saying prayers for the happiness of mother, they heap the second tower;

Saying prayers for their brothers, their sisters, and all whom they

loved at home, they heap the third tower.

Such, by day, are their pitiful diversions.

But ever as the sun begins to sink below the horizon,

Then do the Oni, the demons of the hells, appear,

And say to them:

What is this that you do here?

Lo! your parents still living in the Shaba-world

Take no thought of pious offering or holy work

They do nought but mourn for you from the morning unto the evening.

Oh, how pitiful! alas! how unmerciful!

Verily the cause of the pains that you suffer

Is only the mourning, the lamentation of your parents.

And saying also, "Blame never us!"

The demons cast down the heaped-up towers,

They dash the stones down with their clubs of iron.

But lo! the teacher Jizo appears.

All gently he comes, and says to the weeping infants:

Be not afraid, dears! be never fearful!

Poor little souls, your lives were brief indeed!

Too soon you were forced to make the weary journey to the Meido,

The long journey to the region of the dead!

Trust to me! I am your father and mother in the Meido,

Father of all children in the region of the dead.

And he folds the skirt of his shining robe about them;

So graciously takes he pity on the infants.

To those who cannot walk he stretches forth his strong shakujo;

And he pets the little ones, caresses them, takes them to his loving bosom

So graciously he takes pity on the infants.

Namu Amida Butsu!

<end quote Lafcadio Hearn>

<also see Beauregard Parish Library E-text Initiative>

For more on Wasan (hymns),

please visit below links.

西院河原地藏和讚」成立攷

Sainokawara Jizo Wasan

Vernacular Hymns Dedicated to Jizo

at the Sai River Beach and Their Possible Age of Compilation

by Manabe Kouzai 真鍋廣濟, ISBN/ISSN: 0287-6000

Click here for a listing of Japanese Wasan

Big Jizo Statue

大地蔵, 新潟県小木町

Niigata Prefecture, Sado Island, Ogi Town

17.5 Meters in Height. Made of Concrete.

Located near Mt. Iwayasan (Wayasan) 岩谷山

Photo Courtesy this J-Site.

|

JŪ-Ō (JUO) 十王

TEN KINGS / TEN JUDGES OF HELL AND JIZO BOSATSU

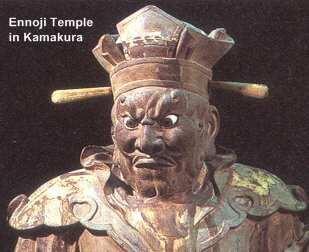

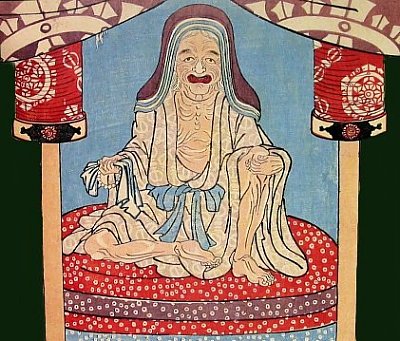

King Shokō (Shoko), the 2nd Judge of Hell

100 centimeters tall, wood, 1251 AD

Treasure of Enno-ji Temple, Carved by Koyu

Now housed at Kamakura Museum (Kamakura Kokuhokan)

Jū-ō (Juo) 十王 TEN JUDGES OF HELL

Adapted from writings of Kondo Takahiro

The Jū-ō (lit. = 10 kings) concept is based on Chinese Taoism and was introduced to Japan during the Heian Period (794-1185 AD). In Kamakura, it flourished in the 14th century, and seems to be the Buddhist counterpart of the Roman Catholic concept of purgatory, the latter stemming in large part from Dante's Inferno. According to the Juo teachings, a wicked person goes to hell after death while a good person goes to paradise. Those whose fate is not yet certain after their death are subject to weekly trials, during which their deeds while living are determined and classified. They are judged by the Ten Kings (the Juo) in the courts of the netherworld. Jizo Bosatsu defends those on trial before the Ten Kings and works to mitigate their punishment. This manifestation of Jizo is known as the Excuse Jizō, for he attempts to make excuses that shed a more favorable light on the behavior of the defendant while still alive.

Enmei Jizo (central image) surrounded by Ten Kings of Hell

Enmei Jizo = long life; prolonger of life; protector of souls in hell

Kamakura Era, Treasure of Nouman-in Temple (能満院), Nara

Thirteen Buddhist Deities (十三仏 or 十三佛)

This topic is explored in-depth in an 84-page

Condensed Visual Classroom Guide (click here to view).

Below are quick links to the deities and hell concepts involved.

|

Thirteen Buddhist Deities (十三仏 or 十三佛)

13 Butsu of Shingon Memorial Services &

Stages of Judgment by the Ten Kings of Hell

Thirteen Buddhist Deities (Jūsanbutsu 十三仏), including Buddha 仏, Bodhisattva 菩薩, and Myō-ō 明王, are important to the Shingon sect of Japanese Esoteric Buddhism. The 13 are invoked at 13 postmortem memorial services held by the living for the dead and 13 premortem services held by the lviing for the living. They are associated with the 10 Kings of Hell. This Grouping of 13 appeared around the 14th century and is considered a purely Japanese convention.

|

|

Judgement

Timeframe

|

Name

of Judge

|

Kanji &

Hiragana

|

Honjibutsu

Buddhist counterpart

|

|

1st week, 7th day

初七日

|

Shinkō-ō

|

秦広王

しんこうおう

|

不動明王

Fudō Myō-ō

|

|

2nd week, 14th day

一四日

|

Shokō-ō

|

初江王

しょこうおう

|

釈迦如来

Shaka Nyorai

|

|

3rd week, 21st day

二一日

|

Sōtei-ō

|

宋帝王

そうていおう

|

文殊菩薩

Monju Bosatsu

|

|

4th week, 28th day

二八日

|

Gokan-ō

|

五官王

ごかんおう

|

普賢菩薩

Fugen Bosatsu

|

|

5th week, 35th day

三五日

|

Enma-ō

Yama (Skt.)

|

閻魔王

えんまおう

|

地蔵菩薩

Jizō Bosatsu

|

|

6th week, 42nd day

四二日

|

Henjyō-ō

|

変成王

へんじょうおう

|

弥勒菩薩

Miroku Bosatsu

|

|

7th week, 49th day

七七日49日

|

Taizan-ō

|

泰山王

たいざんおう

|

薬師如来

Yakushi Nyorai

|

|

During the seven weeks following one’s death, tradition asserts that the soul wanders about in places where it used to live. On the 50th day, however, the wandering soul must go to the realm where it is sentenced (one of the six realms). The 49th day is thus the most important day, when the deceased receives his/her karmic judgment and, on the 50th day, enters the world of rebirth. A service is held to make the “passage” as favorable as possible. Prayers are thereafter offered at special intervals, and performed indefinitely starting in the 13th year. <Source: Flammarion, p. 340>

|

|

100th day

百カ日

|

Byōdō-ō

|

平等王

びょうどうおう

|

観世音菩薩

Kannon Bosatsu

|

|

1st year

一回忌

|

Toshi-ō

|

都市王

としおう

|

勢至菩薩

Seishi Bosatsu

|

|

3rd year

三回忌

|

Gotōtenrin-ō

|

五道転輪王

ごどうてんりんおう

|

阿弥陀如来

Amida Nyorai

|

|

Three more hell kings, along with three more Buddhist deities, were added to the above ten.

|

|

7th Year

七回忌

|

Renjō-ō

|

れんじょうおう

|

阿閦如来

Ashuku Nyorai

|

|

13th Year

十三回忌

|

Bakku-ō

|

ばっくおう

|

大日如来

Dainichi Nyorai

|

|

33rd Year

三十三回忌

|

Jion-ō

|

じおんおう

|

虚空蔵菩薩

Kokūzō Bosatsu

|

|

NOTES

- Group #2. Above timetable (linked to the 10 Kings of Hell) is not commonly used in contemporary Japan. Instead, for memorial services in modern times, the 13 deities are invoked at the intervals shown below:

- Fudō Myō-ō 不動明王 (7th day)

- Shaka Nyorai 釈迦 (27th day)

- Monju Bosatsu 文殊 (37th day)

- Fugen Bosatsu 普賢 (47th day)

- Jizō Bosatsu 地蔵 (57th day)

- Miroku Bosatsu 弥勒 (67th day)

- Yakushi Nyorai 薬師 (77th day)

- Kannon Bosatsu 観音 (100th day)

- Seishi Bosatsu 勢至 (1st anniversary)

- Amida Nyorai 阿弥陀 (3rd anniversary)

- Ashuku Nyorai 阿閦 (7th anniversary)

- Dainichi Nyorai 大日 (13th anniversary)

- Kokūzō Bosatsu 虚空蔵 (33rd anniv.)

<Sources: JAANUS, Shingon Buddhist International Institute, Tobifudo (Shingon Temple in Tokyo), and Dr. Gabi Greve’s 13 Buddha Page.>

- <Says JAANUS>: Thirteen Buddha are thought to have developed from the Chinese belief in ten kings of the underworld (Jū-ō 十王) who were regarded as manifestations of Ten Buddha (Jūbutsu 十仏), to whom three more deities were added in later times. In addition to statuary sets of the thirteen, there exist many stone tablets (itabi 板碑) portraying these deities or inscribed instead with their seed-syllables (shuji 種子). They are similarly represented in hanging scrolls that are still used today at memorial services for the dead.

- <Says the Dictionary of Chinese Buddhist Terms by Soothill and Hodous: The thirteen Shingon rulers of the dead during the forty-nine days and until the thirty-third-year commemoration. The thirteen are 不動明王, 釋迦 (釈迦), 文殊, 普賢, 地藏, 彌勤, 藥師, 觀音, 勢至, 阿彌陀, 阿閦, 大日and 虛空藏; each has his place, duties, magical letter, signs, etc.

|

|

OVERVIEW. In Japan, a memorial service is held on the 28th day after one’s death, presided over by the Thirteen Buddhas (Jūsanbutsu 十三仏). On the 35th day following death, Enma-ō (Skt. = Yama, the 5th judge, often shown holding the Wheel-of-Life in Tibetan Tanka) makes his ruling after hearing the judgments passed down by the first four kings. Offerings by living relatives are especially important on the 35th day following death, as this is the day the defendant is sentenced by Enma to one of six realms of existence -- (1) Hell; (2) Hungry Ghosts; (3) Animals; (4) Asura; (5) Human Beings; (6) the heavenly Deva realm. All six realms are stages of suffering, even the heavenly realm of the Deva, who it is said suffer from pride. The sixth judge of hell, Henjo-o, decides your placement within the realm you are sentenced (reborn) into. For example, for those to be reborn into the human realm, Henjo-o may sentence you to be reborn as a wealthy or poor person, as a peaceful or violent person. The 7th judge, Taizan-o, dictates the conditions of rebirth, such as one’s life span and one’s sex, male or female. During the seven weeks following one’s death, tradition asserts that the soul wanders about in places where it used to live. On the 50th day, however, the wandering soul must go to the realm where it was sentenced (one of the six realms). Even so, for those sentenced to the lower realms, there is a way out. Among believers of the Jodo Pure Land sect, those sentenced to the realm of hell, hungry ghosts, animals (beasts), or Asura (the realm of anger) may gain salvation, but only if they remain religious and only if their living relatives hold a mass on the 100th day following their death, and another mass on the first year following their death, and yet another mass on the second year following their death. Enma is considered the most important of the ten judges, and in artwork Enma is thus frequently placed in the center.

|

|

At Ennoji Temple in Kamakura, one can view statues of the Excuse Jizō and the 10 Judges of Hell. Most of these statues were made in the Edo Period (1603-1868 AD). Ennoji Temple is the 8th site on the Pilgrimage to 24 Kamakura Sites Sacred to Jizo. Statues of the Ten Kings can also be seen at Engakuji Temple. The Kamakura Museum (Kamakura Kokuhokan, inside Tsurugaoka Hachimangu Shrine) also exhibits a number of hell-related statues from Ennouji Temple.

100 centimeters tall, wood, 1251 AD

Treasure of Enno-ji Temple, Carved by Koyu

Now housed at Kamakura Museum (Kamakura Kokuhokan)

|

Kushōjin (Koshojin) 倶生神

Also spelled Kujōjin, Kujojin, Gushōjin, Gushojin, Gushōshin, Gushoshin. Assisting the 10 Kings are the Kushoujin. Of Hindu and/or Chinese Taoist origin, but later incorporated into Buddhism, the Kushoujin (also read Kujyoujin or Gushoujin) are two deities who keep a complete record of our life. Once a baby is born, the pair records the child’s behavior until the child’s death. One records only good behavior, while the other records only bad behavior. Some sources say their reports are presented to Shinkou-ou, the first of ten judges in hell. However, most sources say their records are instead presented to Enma-ou, the fifth judge of hell. The Japanese believe that the Kushoujin stand on our shoulders from the moment we are born until the moment we die, keeping careful accounts of our actions. In some accounts, the deity standing on the left shoulder is male, named 同名 or 同名天 (Shimei). He records our good actions. On the right shoulder stands 同生 or 同生天 (Shisei), female, who records our bad actions.

The Kushoujin (treasures of Ennoji Temple in Kamakura).

Kamakura Era (1185-1333); now at the Kamakura Museum.

Once a baby is born, the Kushojin keep records

of the child’s behavior until the child’s death. One Gushojin

records only good behavior, while the other records bad behavior.

Their reports are used by the Ten Kings to pass judgement.

|

PHOTOS OF THE KINGS OF HELL

King Enma and Attendants

Treasures of Hoshaku-ji Temple, Kyoto.

Photo courtesy Kyoto National Museum

Color on wood, Height 110.5 cm, Kamakura Era (13th Century)

The museum, however, gives different names to the Kushoujin.

Shimei (museum = Ankoku-doji) lists the sins of the dead person.

Gusho-shin (museum = Kushoujin) lists up the good deeds.

The legends reported above about these two thus differ, so

I’m unsure of the exact iconography & naming conventions.

|

|

Kisoutsu, Jailer in Hell

Wood, Enno-ji Temple, Kamakura Era

On display at the Kamakura Museum (Kamakura Kokuhokan) |

Datsueba -- Old Hag of Hell

Plus Blood Pool Hell for Women

Datsueba (also Datsue-ba), spelled either 奪衣婆 or 脱衣婆. The characters 脱衣 literally mean to undress, to "take off one's clothes," or to “stripe one of one’s clothing.” Also known as Sanzu no Baba 三途の婆, Shōzuka no Baba, and Jigoku no Baba 地獄の婆.

According to Japanese Buddhist folklore (mostly from Japan’s Pure Land sects), when a child dies, its soul has to cross the River Sanzu (Sanzu No Kawa 三途の川, River of Three Roads, River of Three Crossings, akin to the River Styx in Western myth), which lies between the first and second Judges of Hell (between the kings Shinkō-ō and Shokō-ō; see above).

At the river's edge (before crossing it), the bewildered soul is advised by the hellish hag Datsueba to make a pile of pebbles on which to climb toward paradise. But before the pile reaches any small height, the hag and underworld demons viciously knock it down.

After the first trial by Judge Shinkō-ō, the dead who are found innocent can cross the river, walking on a bridge guided by Jizō. The guilty, however, must swim across deep waters and the less guilty ford across a rapid stream. At the other side of the river, the old hag Datsueba waits for the guilty to arrive and then robs them of their clothes. Those who arrive without their clothes are instead stripped of their skin.

Datsueba by Kuniyoshi (1797-1861 AD)

Courtesy www.printsofjapan.com

- Shozuka no Baba. Says the Flammarion Guide: “In Japan, popular belief holds that a hideous creature by the name of Shozuka-no-Baba strips children of their clothing, then encourages them to make piles of stones to build a stairway to paradise. Ksitigarbha consoles the afflicted children and, to save them, hides them in the wide sleeves of his robe. The Japanese in the countryside often attach small pieces of children’s clothing to the statues representing Jizo, believing that he can thus clothe the children in his protection.” < Editor’s Note: Shozuka no Baba is none other than Datsueba >

Abstract of Story by Kawamura Kunimitsu

The Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies

www.columbia.edu/cu/ealac/imjs/reports/1994-04/

Datsueba 奪衣婆 is an old-lady demon who is one of the keepers of hell. Her function is to strip the clothing from sinners when they first arrive at the riverbank of hell (Sanzu no Kawa | 三途の川 | さんずのかわ | The River of Three Crossings, or the River of Three Roads). She does not ferry souls to hell. Rather, she sits by the river and strips those who arrive of their clothes, which her male counterpart, the old man Ken’eo (Ken’eō) 懸衣翁 hangs on a riverside tree branch before the sinners are sent on their way -- with the bending of the branch indicating the gravity of the former owner’s sins. (** Editor: there is some confusion here. Does Datsueba meet them before they cross the river, after they cross the river, or on both sides of the river? This is unclear.**)

Datsueba makes her first appearance in Japan in the Bussetsu Jizō Bosatsu Hosshin Innen Juō Kyō 仏説地蔵菩薩発心因縁十王経, a late Heian-era Japanese sutra (based on a Chinese counterpart) dealing with Jizo Bosatsu and the Ten Kings of Hell. Datsueba is paired with an old-man named Ken’eo (Ken’eō) 懸衣翁. The old-woman hag Datsueba forces the sinners to take off their clothes, and the old-man Ken’eo hangs these clothes on a riverside branch that bends to reflect the gravity of the sins. Various levels of punishment are performed even at this early stage. For those who steal, for example, Datsueba breaks their fingers, and together with her old-man consort, she ties the head of the sinner to the sinner’s feet. Ultimately, the sinners are sent off to receive judgment from the ten kings of hell. The next work that refers to Datsueba is the "Hokke Genki" of 1043 AD. In 1257 AD, another source mentions that if a sinner arrives with no clothes, Datsueba strips the sinner's skin. Datsueba also appears in a Muromachi-Era Monogatari called "Tengu no Dairi."

Datsueba 奪衣婆 and Ken’eō 懸衣翁

Modern stone statues at Hase Dera in Kamakura

NOTE: Above two statues look very similar to another pair

held by the Tsurugaoka Hachimangu Museum (Kamakura).

The museum’s two statues were made in the Kamakura Era.

One may argue that Datsueba is not only a demon who strips sinners of their garments (or skins). She is also a goddess, one who bestows humans with their skin coverings at the time of their birth. She can thus be seen as a goddess of life and a demon of death, one who both gives and takes away the skin that covers the human body. <end quote from the Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies; text by Kawamura Kunimitsu>

RANDOM NOTES

Blood Pool Hell (Blood Basin Hell)

Blood Pool Hell (Jp. = Chi no Ike Jigoku = 血の池地獄)

Blood Pool Hell Sutra (Jp. = Ketsubonkyou; 血盆経)

Also called the “Menstruation Sutra”

- According to some sources, there was a special torment reserved for certain women called the Blood Pool Hell 血の池地獄 (Jp. = Chi no Ike Jigoku). It is closely related to belief systems dealing with pregnancies, both successful and failed. Here Datsue-ba played a different role and evolved into "a guarantor of safe childbirth." At birth she provides each child with a "placental cloth" which must be returned at the time of death. <Source: www.printsofjapan.com. Editor’s Note = still need to confirm>

- Quote from Takemi Momoko’s “Menstration Sutra Belief In Japan.” The Bussetsu Daizou Shoukyou Ketsubon Kyou (The Buddha's correct sutra on the bowl of blood) is a rather short (totalling some 420-odd characters) sutra found on p.2999 of the fourth volume of the eighty-seventh section of the first part of Dai nihon zoku zoukyou ("Great storehouse of Japanese sutras, continued"). A sutra that teaches the way of salvation for women who have fallen into Hell because of the pollution of blood, this document appears to have had widespread circulation in China from the time of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). There is, however, a variety of works referred to as "Ketsubon kyou" (lit. "Blood bowl sutra"), including those from Buddhism, Taoism or certain individual Shinto shrines, and the content of each of these differs somewhat from all the rest. In this article I will limit my investigations to the sutra as it was circulated in Japan, but there are a variety of Japanese versions as well, all of which differ slightly. First, then, I will clarify the nature of these differences, and then discuss "Ketsubon Kyou" belief in Japan after attempting to date its transmission to this country. < Source: Nanzan Institute for Religion & Culture, Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 10/2-3 1983; by Takemi Momoko, translated by W. Michael Kelsey from "Nihon ni okeru Ketsubonkyou shinkou ni tsuite." Click here for the story in PDF format.

- See the dissertion of scholar Hank Glassman (Stanford University, 2001) entitled The Religious Construction of Motherhood in Medieval Japan. Chapter Four in particular concerns the Blood Pool Hell. Click here for Chapter Four in PDF format (source: Haverford College, Pennsylvania)

- In 2005, scholar Duncan Williams published “The Other Side of Zen: A Social History of Soto Zen Buddhism in Tokugawa Japan.” Chapter three of this book, entitled “Funerary Zen: Managing the Dead in the World Beyond,” deals with the Blood Pool Hell Sutra (Jp. = Ketsubonkyou)and how it was exploited by authorities at Shousenji Temple (正泉寺). According to Williams, female parishioners and nuns were told that reciting the Blood Pool Hell sutra was the only way for females to avoid damnation. Book published by Princeton University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-691-11928-7.

- The Kumano Kanjin Jikkai Mandara depicts the Nyoirin Kannon as bringing salvation to women in the Blood Pool Hell. One of the six arms of the Nyoirin Kannon is shown holding a scroll, which most scholars would agree is the Blood Pool Hell Sutra (Blood Basin Sutra). But there is no way to be sure -- scholar Barbara Ruch suggests the it may be The Heart Sutra (Hannya Shingyou). < quote from Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, p. 192-193, 33/1 (2006) >

- Future Research Topics

血の池 (ちのいけ) = Blood Pond (or Pool); Chi no Ike

姥石 (うばいし) = Old Woman Stones

鬼婆 (おにばば) = Oni Baba (Demon Witch)

|

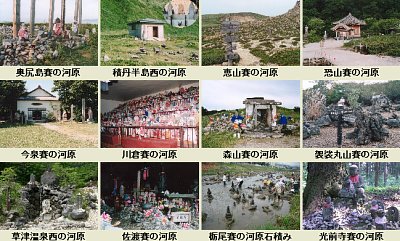

List of Sai-no-Kawara Sites in Japan

Adapted from list created by Dr. Gabi Greve. Thanks Gabi-san !

There are many areas in Japan named Sai no Kawara (Sainokawara), although the majority are located in northern Japan. Grieving parents go to these locations to pray and make offerings in an attempt to pacify the soul of their lost child and to pacify their own soul as well. A partial list of these sites is presented below. According to some, the concept of Sai no Kawara originated in pre-Buddhist folk belief, but it is nearly impossible to confirm this, as Japan’s first written records occur only after the introduction of Buddhism.

Click above photo for list of Sai-no-Kawara sites nationwide.

Japanese language. Some of these locations are explained below.

- Okushiri Island in Hokkaido

奥尻島賽の河原 (北海道奥尻郡奥尻町稲穂)

sainokawara.fubuki.info/okusiri.html

- Shakotan Peninsula in Hokkaido

積丹半島西の河原 (北海道古宇郡神恵内村珊内)

sainokawara.fubuki.info/syakotan.html

- Mt. Esan in Hokkaido

恵山賽の河原 (北海道函館市恵山)

sainokawara.fubuki.info/esan.html

www.hiyama.or.jp/soul/sai-2/default.htm

- Imaizumi in Aomori Prefecture

今泉賽の河原 (青森県北津軽郡中泊町今泉)

sainokawara.fubuki.info/imaizumi.html

- Kawakura in Aomori Prefecture.

川倉賽の河原 (青森県五所川原市金木町川倉七夕野)

sainokawara.fubuki.info/kawakura.html

www.ne.jp/asahi/sp/a/n1.html

Within the temple compounds are many items offered to the dead, like warm coats for winter and tennis shoes. People sometimes even offer bicycles for the dead children. It looks like the shop of an old clothes and dolls dealer, but these are all offerings.

- Mt. Iwasaki (Iwasaki-san) in Aomori Prefecture.

岩崎賽の河原 (青森県西津軽郡深浦町森山)

sainokawara.fubuki.info/iwasaki.html

www.mutusinpou.co.jp/news/04082408.html

There is a special festival for dead children during August 23/24, Iwaki Sai no Kawara Daisai. Half way up the mountain beside the small shrine are mountains of tennis shoes, sweets, windwheels and piled-up pebbles. Old people would not hesitate to take the steep climb from the cable car to the top of the mountain to pray for the eternal rest of the souls. It is a very moving sight to see all these people climb through mist and strong wind to the top of stony Mt. Iwaki.

- Kesamaruyama in Gunma Prefecture

袈裟丸山賽の河原 (群馬県勢多郡東村)

sainokawara.fubuki.info/kesamaruyama.html

- Kusatsu Hot Spring in Gunma Prefecture

草津温泉西の河原 (群馬県吾妻郡草津町大字草津)

sainokawara.fubuki.info/kusatu.html

- Sado Island, Niigata Prefecture. This one is on the beach near the sea, a typical location for many Sai-no-Kawara sites. 佐渡願の賽の河原 (新潟県佐渡市願)

sainokawara.fubuki.info/sado.html

www41.tok2.com/home/kanihei5/sadosainokawara.html

- Kouzen-ji Temple in Nagano Prefecture

光前寺賽の河原 (長野県駒ヶ根市赤穂29 光前寺)

sainokawara.fubuki.info/kozenji.html

- Mt. Daisen, The Big Mountain, in Tottori Prefecture

www.page.sannet.ne.jp/katsu-imamura/daisen2.html

- Cate Kodo Juno, an ordained Buddhist priest of Japan's Shingon sect, has created a web site named SacredJapan.com which reviews all 33 temples along the Saigoku Sanjūsan Kannon Reishō (a popular pilgrimage circuit devoted to Kannon). Ichijōji Temple 一乗寺 (Kasai City, Hyōgo Prefecture)is the 26th temple on the circuit. Writes Cate: “This melancholy place with many cairns of stones and little Jizō statues, represents the shore of the River Sai where the spirits of departed children and babies gather. While they are there, they are forced to build up piles of stones to make their own stairway to paradise, and then an old hag demon comes and knocks them down. But Jizō comes to the rescue, taking them away in the folds of his robes to the Pure Land. Grieving parents come here to build cairns on behalf of their departed children so that they will not suffer as much while they await Jizō to take them into the next life. It is a very sad place with offerings of children's toys and candy strewn around the rocks. The sense of grief is palpable here. <end quote>”

Mt. Osore, Osorezan

Mountain of the Dead, 霊場恐山

恐山賽の河原 (青森県むつ市田名部字宇曾利山)

sainokawara.fubuki.info/osorezan.html

Mt. Osore, located in Mutsu and two neighboring towns in Aomori Prefecture, is regarded as a sacred mountain. The smell of sulfur hangs in the air, and it is dotted with small cairns of stones erected by pilgrims at places called "Sai no Kawara" -- Buddhist rivers believed to be home to the souls of deceased children. Atop the piles of stones, pinwheels, left by parents praying for the transmigration of their departed children's souls, chatter in the wind. It has long been believed in the Shimokita region of the prefecture, that the souls of the dead congregate on Mt. Osore, or Osorezan. <above paragraph quoted from Yomiuri Shimbun>

Hotoke-ga-Ura is the westernmost part of the Osorezan Buddhist world. From here the lucky souls who have passed judgement are delivered directly to Amida's Paradise in the West. The rough mountains in this area look like Buddha statues, and a huge area is reserved for the dead children.

Every year, during the grand festival of Osorezan Taisai, held from July 22 to 24, people climb the mountain to "talk" with the souls of the dead through Itako (female shamans) who act as mediums. The female Itako Shamans of Osorezan are a phenomen in themselves -- they speak an almost incomprehensible Tsugaru (津軽) dialect, but they play an important role in connecting the dead with their grieving parents and relatives. For a QuickTime video of a female shaman from Tsugaru, click here. Film by Yasuhiro Omori from the research department of the National Museum of Ethnology.

Jizo surrounded by prayer stones at Sai-no-Kawara, Osorezan

Photo courtesy Ellen Schattschneider

Prayer Pillars at Osorezan Lake

Click here for more photos from this source

Jizo at Shiroyama (in Hachioji, Tokyo)

Photo by Andy Gray at www.japanwindow.com

|

WEDDINGS FOR THE DEAD

JIZO BRIDE DOLLS, KOKESHI DOLLS

FOR THE DEAD, AND INFANTICIDE IN JAPAN

Bride Dolls, Family Resemblances

Memorial Images and the Face of Kinship

Click above link for story by Ellen Schattschneider, assistant professor of Anthropology at Brandeis University, about hanayome-ningyo (bride dolls) infused with the spirit of the Jizo Bosatsu and presented to deceased souls by mourning parents and relatives.

Kokeshi Dolls for the Dead

|

LEARN MORE LEARN MORE

This page relies heavily on the wonderful database of the Japanese Architecture & Art Net User System (JAANUS), the writings of longtime Japan resident Dr. Gabi Greve, the research of American anthropologist Ellen Schattschneider (Brandeis University), and many other authors including Lafcadio Hearn, Alan Booth, Elaine Marting, Gorai Shigeru, Kondo Takahiro, Kawamura Kunimitsu, and the publications of the Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, the Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies, and Japan’s National Museum of Ethnology. See below for links to their online work.

|

- Sai no Kawara by Dr. Gabi Greve. More on the Japanese legend of Children’s Limbo.

Click here for other pages by Dr. Gabi Greve.

- Bride Dolls, Family Resemblances. Memorial Images and the Face of Kinship. Story by Ellen Schattschneider, assistant professor of Anthropology at Brandeis University, about hanayome-ningyo (bride dolls) infused with the spirit of the Jizo Bosatsu and presented to deceased souls by mourning parents and relatives.

- Japanese Architecture & Art Net User System DATABASE

- Quicktime Video of a Female Shaman from Tsugaru. Film by Yasuhiro Omori from the Research Department of the National Museum of Ethnology. If it doesn’t work, try clicking here.

- Shugendo and Its Lore, by Gorai Shigeru. Written for the Japanese Journal of Religious Studies (1989, 16/2-3). Interesting historical notes on boundary stones and hell-related locations.

- List of Sai-no-Kawara Sites in Japan (see above list)

- Ceremony for Children Who Have Died (San Francisco, US). Web home of Yvonne Rand, a Soto Zen Buddhist priest and meditation teacher. For over 30 years she has attended people suffering from life-threatening illnesses, people in the late stages of dying, and people who have lost a family member or a friend.

- Japanese Wasan (Hymns)

THIS IS A SIDE PAGE

CLICK HERE TO RETURN TO MAIN JIZO PAGE

|

|