|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A Kick-Start Card from Keiko & Mark Schumacher. Music by Mark.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

JAPANESE VOTIVE TABLETS OF THE FOWL

|

|

Known as EMA 絵馬 (literally "HORSE PICTURES"), votive tablets can be purchased at most shrines and temples for around $10 or less. You write your name and petition (prayer) on the back, and then hang the tablet inside the compound in the hope the kami (deity) will answer your prayer. Says JAANUS: "Illustrated wooden plaques given as votive offerings to shrines and temples. It is believed that the custom of donating ema has its roots in the ancient practice of presenting a sacred white horse (shinme or jinme 神馬) to a shrine for use in rituals and as an auspicious symbolic messenger of the gods. Later, small wooden statues of these sacred horses were presented as substitutes. These statues were then simplified to images of a horse carved in relief, usually on a wooden plaque. By the late Edo period (18th century), paintings on ema came to depict not only the sacred horse but also a great variety of other subjects" -- including the twelve animals of the Asian Zodiac.

|

|

Sankyozawa Fudōson 三居沢不動尊, Sendai

The word "fortune" 福 is written on

a green bag containing money.

|

Hie Shrine 日枝神社, Gifu.

To bring luck, ward off evil, ensure family

safety, and engender business success.

|

Ōtori Shrine 大鳥神社, Tokyo (Meguro).

To bring good luck and family safety.

Shown here is a family of chickens.

|

|

Niukanshōbu Shrine 丹生官省符神社, Wakayama.

Shrine priest blessing a giant votive plaque.

|

Ikuta Shrine 生田神社, Kobe. Shrine maidens

standing by giant billboard-size votive plaque.

|

Gokoku Shrine 護国神社, Nagano.

Giant billboard-size votive plaque.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

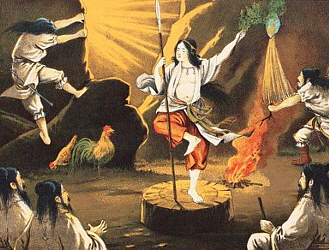

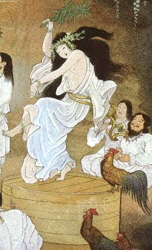

RELIGIOUS LORE IN JAPAN -- SUN GODDESS, ROCK CAVE, AND ROOSTER

As the herald of dawn, the rooster is naturally considered the servant of Amaterasu (Japan's native sun-goddess).

|

|

Japan's earliest surviving texts -- the Kojiki (712) and Nihon Shoki (720) -- tell tales of ancient Japanese gods and heros. One of the central episodes in these early court histories recounts how sun-goddess Amaterasu 天照, harassed and frightened by her brother, Susano-o 須佐之男命, retired into a rock cave, plunging the world into darkness. To mend the situation, all of Japan's myriad local native deities (kami 神) gathered together to formulate a plan. In both the Kojiki (p. 63) and Nihon Shoki (p. 42), one of the strategies was to order the "crying birds of Tokoyo" to come to the cave and "cry" their rooster-like sound. At Ise Shrine (stronghold of Amaterasu worship even today), there is a rite in which priests make a crowing noise "like a rooster" before entering the shrine [See Breen/Tweeuwen, p. 135]. The term "Tokoyo" 常世 means "eternal world," and refers to a divine land located across the sea. In the passage from the Nihon Shoki, the roosters from across the sea from Ise bring an end to the "eternal night" with their crowing. Roosters are thus represented in [modern] paintings of Amaterasu, who was eventually coaxed out of the rock cave, thus bringing sunlight back to the world. This myth has many meanings. Among them is the pre-modern explanation of sun eclipses, or of the sun's decline in autumn and "rebirth" after the winter solstice. [See Breen/Tweeuwen, p. 132].

|

|

Ame no Uzume's dance to coax the sun goddess out of

her rock cave. Roosters are in attendance. Source.

|

Sun goddess emerges from cave. Source.

|

Ame no Uzume's dance.

Source.

|

Exiting cave.

Source.

|

Exiting cave.

Source.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

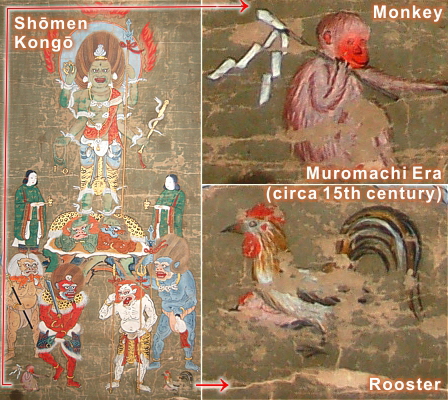

RELIGIOUS LORE IN JAPAN

The rooster is linked to an "all night vigil" that attempts to prolong one's lifespan.

|

|

Shōmen Kongō, Kōshin Vigil, Monkey & Rooster Shōmen Kongō, Kōshin Vigil, Monkey & Rooster

In Japan, certain Zodiac days/years of great misfortune to people born in monkey years are known as Kōshin 庚申 (Chn = gēngshēn). In Taoist traditions from China, first documented in the 4th century CE, at the start (midnight) of a Kōshin day, THREE WORMS 三蟲 (or three corpses) dwelling in the human body escape and visit the Court of Destiny 司命 (ruled by the Emperor of Heaven 天帝) to report on the sleeping person's sins. Depending on this report, the Court might decide to shorten the individual's life. To prevent this, people stay awake from midnight to daylight on Kōshin days, gathered around scrolls of Shōmen Kongō. Over time, this practice became known in Japan as the Kōshin Machi 庚申會 (Kōshin Vigil). In Japanese art, Shōmen Kongō is often accompanied by a monkey and a rooster. The monkey is a major player in Kōshin rituals, for the term Kōshin 庚申 includes the ideogram 申, meaning monkey. The rooster symbolizes the dawn following the vigil -- the danger has passed for those who stayed up all night. Today, Shitennō-ji Temple 四天王寺 in Osaka is the most revered site in Japan for Kōshin rites, which it holds six times yearly. At the ritual, believers are gathered before scrolls of Shōmen Kongō and pummeled, from head to legs, with a wooden monkey figurine, which apparently ensures future health. The ritual's rules are: don't speak evil, don't use bad language, don't get angry, don't get caught up in passion, don't think evil thoughts, don't think of sex, don't eat the flesh of animals with four or two feet, and don't touch the five strong-smelling vegetables. (Photo: From Private Collection SCC-NY)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHINESE PROVERB 殺雞儆猴

KILL CHICKEN SCARE MONKEY (C = shā jī jǐng hóu)

|

|

Meaning = Harm one person in order to coerce another. Punish an individual as an example to others.

There once was a street entertainer who attracted large crowds with his dancing monkey. Whenever he played the drums, the monkey danced to the rhythm, helping his master earn lots of money. Yet the monkey soon grew tired of this work, and one day refused to dance for his master. In order to force his monkey into compliance, the master brought a live chicken to the monkey and killed it right before his eyes. The monkey got the message and resumed dancing, knowing that if he stopped, he would suffer the same fate. For a different version of this tale, click here.

|

|

|

|

|

LOST IN TRANSLATION

DON'T COUNT YOUR CHICKENS BEFORE THEY HATCH

|

|

This popular English-language adage (etymology here) is expressed quite differently in Japan. The Japanese equivalent does not refer to a chicken and its eggs, but instead to a Tanuki and its fur. The Japanese version is: Don't count your Tanuki skins before catching the Tanuki (Toranu Tanuki no Kawazan yō 捕らぬ狸の皮算用). The Tanuki is an atypical species of dog that is often confused with the badger and the raccoon. It is a real-life animal treasured for its fur, and also a mythological animal -- a magical shape-shifting and mischievous rogue who once haunted, possessed and played tricks on unwary travelers, hunters, woodsmen, and monks. Today, the mythological Tanuki is a cheerful, lovable, and benevolent rogue who brings prosperity and business success. He is easily duped. See Tanuki page for details.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHINESE FOLKLORE

WHY ROOSTERS LOVE EATING CENTIPEDES

|

|

Once upon a time, in old China, the king of animals was the tiger. The dragon,

however, grew envious of the tiger, and the two began fighting, forcing the however, grew envious of the tiger, and the two began fighting, forcing the

Emperor to intervene as judge. Before the day of judgment, the dragon thought

he would look more impressive if he had a jagged crest (horn) like the rooster,

and asked the centipede, a friend of the rooster, to coax the bird into lending his

horn to the dragon. The rooster complied. On judgment day, the dragon and the

tiger both looked ferocious. The Emperor made the dragon the king of water and

the tiger the king of earth. But the dragon refused to return the horn to the

rooster. The rooster thus went after the centipede, and the centipede went into

hiding. To this day, the rooster loves to feed on centipedes. The story comes in different versions: Chinese 1 / Chinese 2 / Okinawan /

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

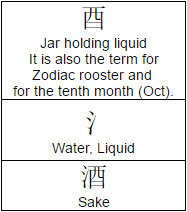

Linguistic Link Between Chickens (Fowl) and Japanese Sake (Liqour)

|

|

In 1978, Japan's sake industry designated October 1st as Nihonshu no Hi (Sake Day). But why October 1st? Why not April 1st? Or May 23rd, or any other day? There are several reasons, notably that Japan's modern-day sake-brewing season typically begins in October. But a more compelling argument is related to the written character for sake 酒. Long ago, in China, it was written 酉, which meant "jar holding liquid," presumably alcohol. This early written form does not include the three short lines 氵found on the left side of sake 酒. The three short lines 氵, incidentally, mean water or liquid. Now enter the Chinese Zodiac and its twelve animal signs. Each Zodiac animal represents one year in a twelve-year cycle, one day in a twelve-day cycle, a two-hour period in a 24-hour day, and other attributes. The tenth of these is "tori" 酉 (fowl, rooster, cock, chicken). It is written exactly the same as "jar" 酉 !!! Why is that? Unknown. But the written characters assigned to the Zodiac animals are not the standard characters used to refer to the animals in normal writing – rather they are special characters with special readings used only when referring to the Zodiac calendar. Another intriguing factor is that jar 酉 (or Zodiac fowl 酉) can be read "to" in Japan. "To" is a Japanese homonym for the number ten – and the Zodiac fowl specifically represents the tenth month and year in any cycle. And, coming round full circle, the tenth month is the beginning of the traditional sake-brewing season. Is that why the first day of the tenth month is known as "Sake Day" in Japan? As with everything in the culture of religion and alcohol, it is hardly random, yet hardly obvious. Therein lies its appeal. (Note: In the Lunar calendar, the 10th month was August. In the modern Gregorian calendar, it is October. Japan switched to the latter in 1872). In 1978, Japan's sake industry designated October 1st as Nihonshu no Hi (Sake Day). But why October 1st? Why not April 1st? Or May 23rd, or any other day? There are several reasons, notably that Japan's modern-day sake-brewing season typically begins in October. But a more compelling argument is related to the written character for sake 酒. Long ago, in China, it was written 酉, which meant "jar holding liquid," presumably alcohol. This early written form does not include the three short lines 氵found on the left side of sake 酒. The three short lines 氵, incidentally, mean water or liquid. Now enter the Chinese Zodiac and its twelve animal signs. Each Zodiac animal represents one year in a twelve-year cycle, one day in a twelve-day cycle, a two-hour period in a 24-hour day, and other attributes. The tenth of these is "tori" 酉 (fowl, rooster, cock, chicken). It is written exactly the same as "jar" 酉 !!! Why is that? Unknown. But the written characters assigned to the Zodiac animals are not the standard characters used to refer to the animals in normal writing – rather they are special characters with special readings used only when referring to the Zodiac calendar. Another intriguing factor is that jar 酉 (or Zodiac fowl 酉) can be read "to" in Japan. "To" is a Japanese homonym for the number ten – and the Zodiac fowl specifically represents the tenth month and year in any cycle. And, coming round full circle, the tenth month is the beginning of the traditional sake-brewing season. Is that why the first day of the tenth month is known as "Sake Day" in Japan? As with everything in the culture of religion and alcohol, it is hardly random, yet hardly obvious. Therein lies its appeal. (Note: In the Lunar calendar, the 10th month was August. In the modern Gregorian calendar, it is October. Japan switched to the latter in 1872).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|